This article is more than 5 years old.

“We have yet had no genius in America, with tyrannous eye, which knew the value of our incomparable materials, and saw, in the barbarism and materialism of the times, another carnival of the same gods whose picture he so much admires in Homer; then in the middle age; then in Calvinism. . . .Yet America is a poem in our eyes; its ample geography dazzles the imagination, and it will not wait long for metres.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Poet” (1843)

The young Walt Whitman heeded Emerson’s call for an American poet, and the result in 1855 was Leaves of Grass.

Whitman had worked as a printer and newspaper publisher, and this first edition of his poetry was self-published in every sense of the word. The book was printed at the shop of Whitman’s friends Andrew and Thomas Rome. The poet himself was involved in all aspects of design and production, even helping to set some of the type.

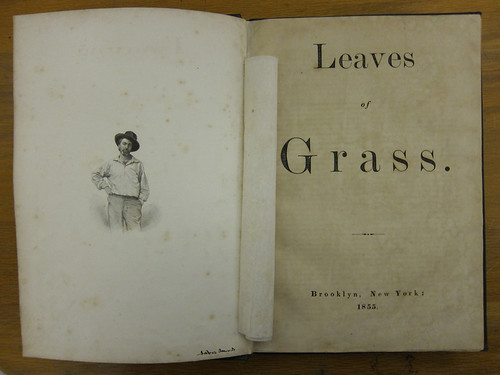

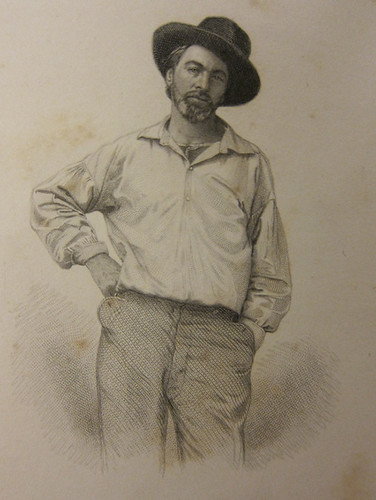

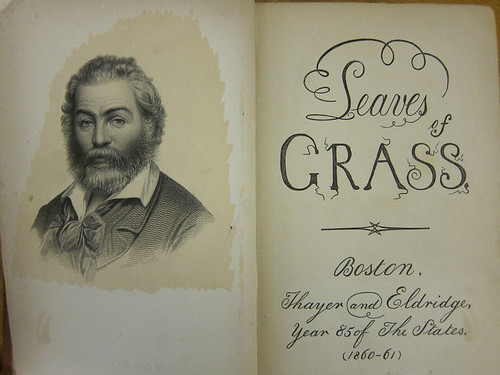

The first edition of Leaves of Grass was, like its author, an oddity in mid-19th century America. Whitman’s name did not appear on the title page; instead his now-famous portrait was featured opposite as a frontispiece.

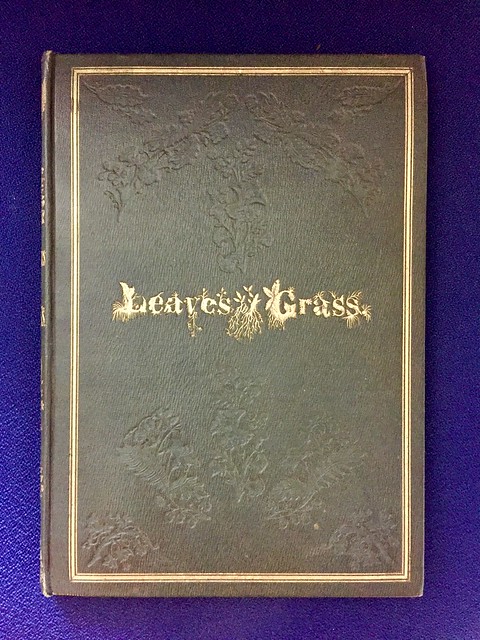

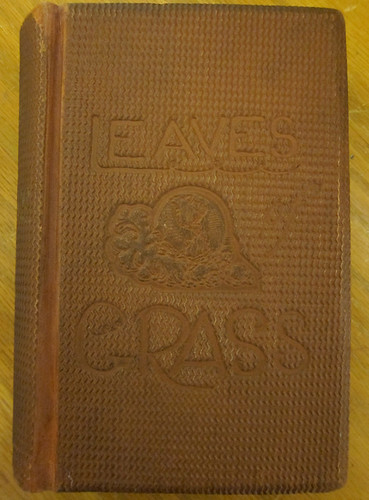

The book is only 95 pages long but is printed on large paper. The size and the leafy decoration and lettering on the dark green covers suggest a Victorian botanical scrapbook.

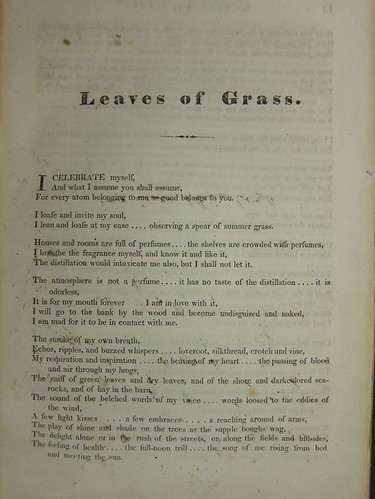

The twelve poems that make up the text of the first edition are untitled. It was not until 1881 that the first and longest was given the name “Song of Myself”.

Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s Special Collections holds two copies of the 1855 first edition of Leaves of Grass. One is from the library of Charles Babcock; the other was purchased in 1954 with funds from the Oscar T. Smith bequest. The O.T. Smith copy includes a page from a 19th century autograph album tipped in at the front, inscribed by Whitman to his friend John H. Johnston and his wife.

The autograph note reads: “Walt Whitman, visiting New York City after an absence of over four years– guest now of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Johnston at 113 East 10th Street. March 15th, 1877.”

The visit was a sadly memorable one. Johnston wrote to mutual friend Horace Traubel on March 17, 1892

Fifteen years ago yesterday Walt was with us when my wife was taken sick and died. He was in the room until the last, and went home next morning after a month’s stay– his first visit.

[Traubel, Horace, With Walt Whitman in Camden (Boston:Small, Maynard, 1906) 607]

Whitman printed 795 copies of the first edition of Leaves of Grass, but the book did not sell particularly well. About 200 copies of the 1855 edition are known to survive today.

Ivan Marki writes in the Walt Whitman Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998) that

The importance of the first edition of Leaves of Grass to American literary history is impossible to exaggerate. The slender volume introduced the poet who, celebrating the nation by celebrating himself, has since remained at the heart of America’s cultural memory because in the world of his imagination Americans have learned to recognize and possibly understand their own. As Leaves of Grass grew through its five subsequent editions into a hefty book of 389 poems (with the addition of the two annexes), it gained much in variety and complexity, but Whitman’s distinctive voice was never stronger, his vision never clearer, and his design never more improvisational than in the twelve poems of the first edition.

Whitman continued to tinker with Leaves of Grass throughout his entire life, giving it one of the most complicated publishing histories of any major American literary work. The second edition, published by Whitman in 1856, was smaller in format and included twenty additional poems.

In 1860 the progressive new Boston publishing firm Thayer & Eldridge came out with a third edition.

The third edition included another 120 new poems as well as Whitman’s revisions of poems from the first two editions. Whitman’s friends referred to the new frontispiece engraving as his “Byronic portrait”.

This was Whitman’s first publication by a commercial press. The poet’s reputation had grown since the first Leaves of Grass, and the third edition sold reasonably well. Unfortunately Thayer and Eldridge proved not to be astute businessmen, and their firm went bankrupt in 1861. The stereotyped plates were sold to another publisher, who published several more issues of the third edition without Whitman’s permission.

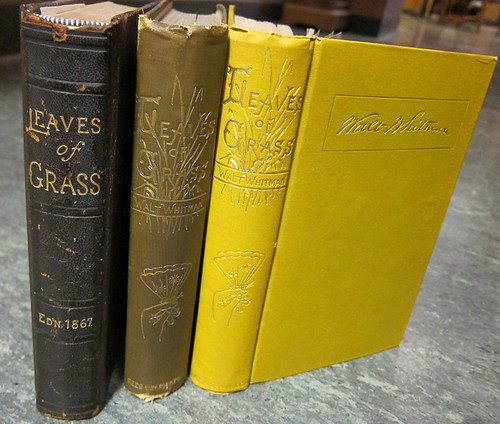

In 1867 Whitman published a fourth edition of the book which incorporated his Civil War poetry. 1871-72 saw a fifth edition that was again revised and reconfigured. The seventh edition of 1881-82 finally achieved a definitive arrangement of the poems; future editions merely appended material to this text.

The seventh edition, published by James R. Osgood of Boston, marked the first time that Leaves of Grass was issued by a major commercial publisher. But when threatened with an obscenity suit by a Boston district attorney, Osgood quickly ceased publishing the book and sold the rights to the Philadelphia firm of Rees, Welsh & Co.

From left to right: WFU’s copies of the 1867, 1881 (Osgood), and 1882 (Rees, Welsh) editions.

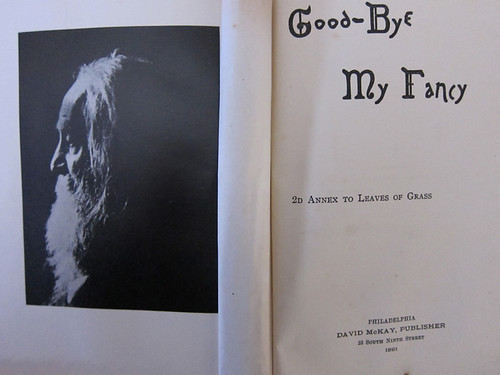

The final “deathbed edition” of Leaves of Grass (1891-92) was really just a reprint of the 1881 edition with the addition of “annexes” of new material.

In “A Backward Glance O’er Travel’d Roads,” an essay appended to this final edition, Whitman addresses future generations of readers:

Result of seven or eight stages and struggles extending through nearly thirty years, . . . I look upon “Leaves of Grass,” now finish’d to the end of its opportunities and powers, as my definitive carte visite to the coming generations of the New World. . . . That from a worldly and business point of view “Leaves of Grass” has been worse than a failure–that public criticism on the book and myself as author of it yet shows mark’d anger and contempt more than anything else . . . is all probably no more than I ought to have expected. . . . I have had my say entirely my own way, and put it unerringly on record– the value thereof to be decided by time.

4 Comments on ‘Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman (1855)’

Excellent and interesting write-up Megan!

I always look forward to your rare book of the month and this is no exception. Great job!

This is so facinating! I have to write a paper on Walt Whitman next week…maybe looking at a first edition of Leaves of Grass will be inspirational.

Excellent to see the focus on Rare’s editions of “Leaves”!