This article is more than 5 years old.

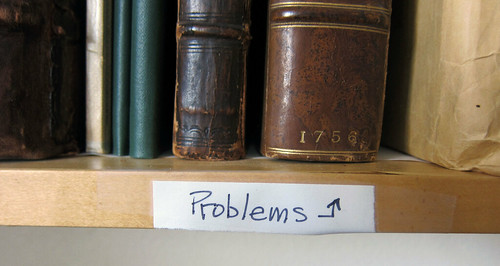

One of the shelves in my office has a small label that reads “Problems.” On it are books that were found, in a recent inventory of ZSR’s Rare Books Collection, to have incorrect or nonexistent catalog records. One of my summer projects this year is to evaluate and create records for this small collection of obscure, odd, or otherwise inexplicable volumes.

Recently I pulled down two volumes bound in dark blue velvet.

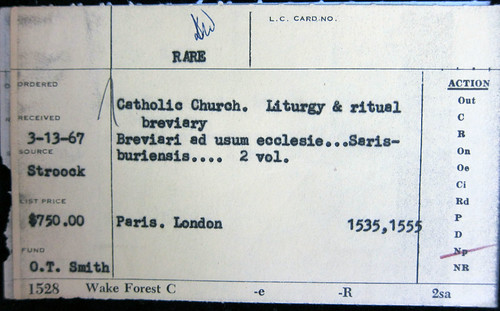

An order slip tucked inside one of the books indicated that they had been purchased by the library nearly 50 years ago. But we could find no indication that they’d ever been cataloged.

Purchased in 1967 from book dealer Paul Stroock, they were supposedly a two-volume set of a breviary—a Roman Catholic liturgy book—of the type known as the Salisbury (or Sarum) usage. This was by far the most common type of Catholic liturgy used in England in the 16th century. Many editions were printed in England or on the continent for English use, especially during the reign of Queen Mary I (1553-1558), when Catholicism was briefly reinstated as the official religion in England.

An initial examination of the books revealed several things. First, the velvet bindings were clearly more recent than the text pages. The decorative metal bosses in the center of the covers, looked like they might date to the 16th century, but the books had been rebound in the 19th or early 20th century, perhaps by a collector or book dealer. What this meant was that the two volumes may not have originally been a matching set, and that the original order of the pages may or may not have been preserved when the books were rebound.

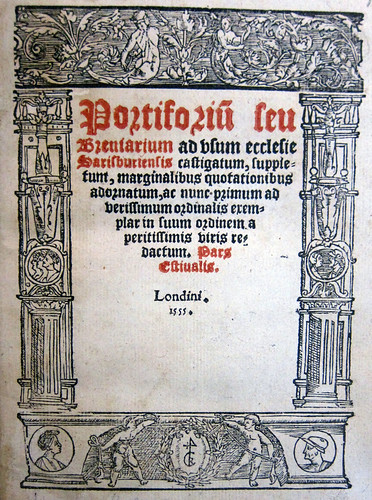

The title page of the first volume indicated that the book was published in London in 1555, but the publisher’s name did not appear.

A check of a standard reference work (R.B. McKerrow & F.S. Ferguson, Title-page Borders used in England & Scotland 1485-1640) indicated that the decorative border and printer’s device originally belonged to Richard Grafton (McKerrow & Ferguson, 48).

Grafton was a successful London printer during the reigns of King Henry VIII (1509-1547) and his son Edward VI (1547-1553)*. He was appointed King’s Printer in 1547. But with the death of the Protestant Edward and the ascension of his Catholic half-sister Mary, Grafton’s fortunes changed, and by 1553 his printing operation had been taken over by Robert Caly, a staunch Catholic. Caly continued to use Grafton’s decorative border, with the printer’s device at the bottom slightly altered to change the initial G into a C. Caly printed many pro-Catholic publications, so it made sense that he would publish a breviary for use in England.

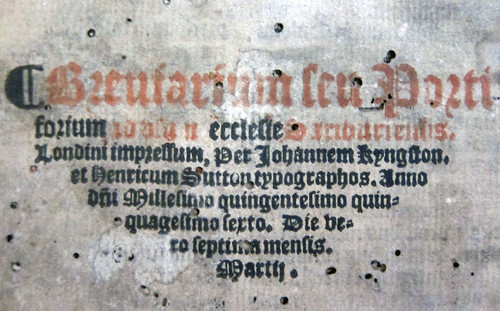

However, at the end of volume I was another publication statement called a colophon. These were common in books from the 16th century (and earlier).

The colophon indicated that the book was printed in London by John Kingston and Henry Sutton in March of 1556, not by Robert Caly in 1555. Kingston and Sutton had also begun printing in London around 1553, taking over the shop of a Protestant printer who had fled to the continent. Kingston had been Richard Grafton’s apprentice, and in his new partnership with Henry Sutton he produced more Sarum liturgies than any other English printer. So Kingston and Sutton were also very plausible candidates for publishers of our volume. But there was no indication that they had ever partnered with Robert Caly, so it made no sense to have both imprints in the same volume.

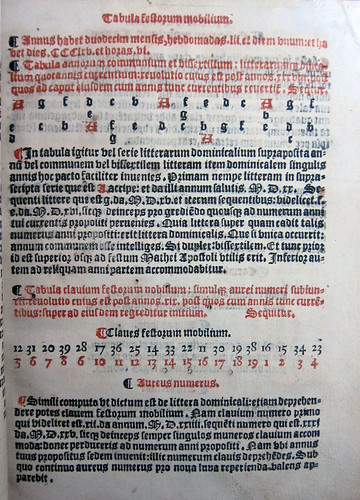

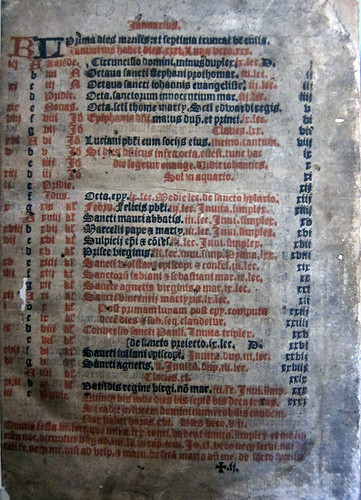

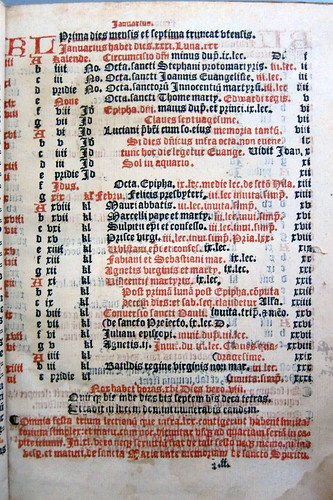

Another feature that struck me as odd was that the page following the volume I title page—the first page of the calendar that begins the breviary—was badly damaged and discolored, as though it had been exposed to the elements over a long period of time. The final colophon leaf (pictured above) had shown the same type of discoloration, as though the book had been used, unbound, for many years. But the title page at the front of the book was relatively clean and undamaged.

Yet another inconsistency in volume I was a bit of text in red on the title page, indicating that it was for the “Pars Estiualis”—the summer section of the liturgy. This made sense, because Sarum breviearies from this period were usually divided into separate volumes for the winter (hiemalis) and summer (estiualis) liturgies. Except that the text of volume I actually began with the winter section, the “Pars Hyemalis.”

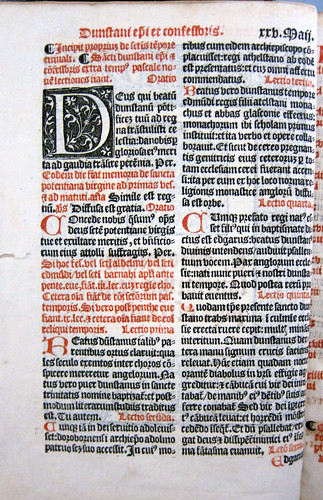

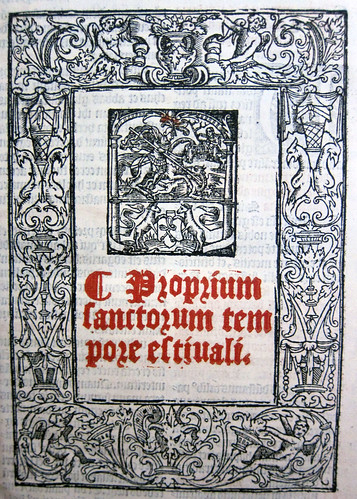

Hoping to find some answers, I turned my attention to volume II. It opened with a page indicating the start of the section of services for the summer liturgy.

Like the title page from volume I, the decorative border on this page was attributed to the printing shop of Richard Grafton (McKerrow & Ferguson, 59), later taken over by Robert Caly.

However, when I turned to the verso—the reverse side of the page– it became clear that this section page was out of place.

How did I know this? In part because the catchword at the bottom right of the page did not match the first word of the following page.

Catchwords are words (or parts of words) found at the bottom of each page of text. They are almost universal in books printed before the 19th century. Catchwords are meant to insure that pages of a books are ordered and bound correctly—the catchword at the bottom of a page should match up with the first word of the text on the following page.

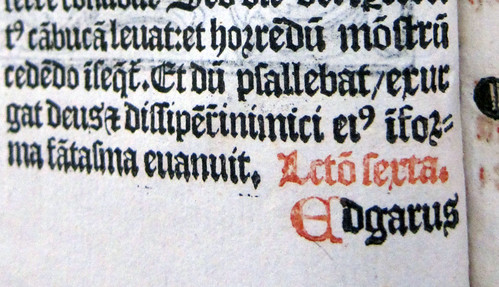

In the case of our breviary, the catchword on the verso of the first page was “Edgarus,” but the next page was a calendar page beginning with the two large initials “K” and “L”.

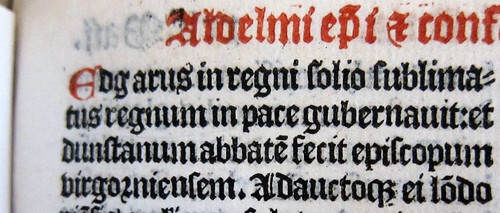

About 100 pages into the volume, I found the text that matched our catchword:

The running heads at the top of the pages also indicated that this was the original placement of the initial leaf. So the “title page” for volume II had been removed from its correct spot and placed at the beginning of the book. But why?

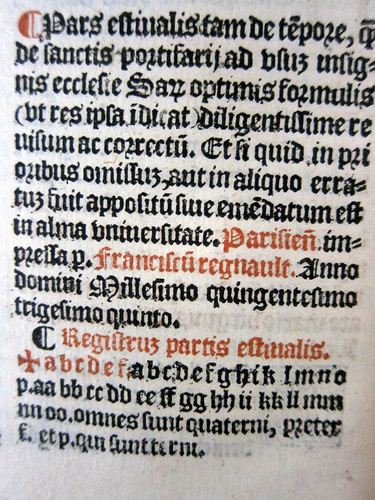

The colophon for volume II further confused the issue. It indicated that the book had been printed in Paris by Francois Regnault in 1535!

So our book had at least three possible printers and three publication dates spanning over 20 years. It was time for some research.

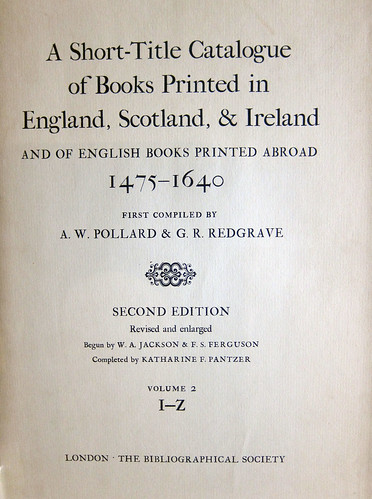

A good starting point for research on 16th century English imprints is A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, & Ireland, originally published by Alfred W. Pollard and G. R. Redgrave in 1926 (later edited and enlarged by other scholars). Popularly known as the STC, it is a monumental work of bibliographic scholarship, accomplished long before the advent of laptops and scanners.

The STC listed several 16th century editions of the Sarum breviary, none of which matched exactly the volumes in our collection. The STC listings included

- An edition printed by Francois Regnault in 1535 (#15833)

- An edition printed by Robert Caly in 1555, which was reprinted from the 1535 Regnault edition and mistakenly included its colophon (#15840)

- An edition printed by John Kingston and Henry Sutton in 1556 (#15842)

ZSR’s volume I matched up perfectly with STC #15842, except for its title page, which was the one associated with STC #15840. Volume II seemed likely to be STC #15840, except that it lacked a title page. Had there been some mixing and matching of pages in our breviary?

A note at the beginning of the STC’s section on liturgies suggested that this was not only possible but quite likely. Pollard and Redgrave observed that “Most bibliographers are hesitant to deal with liturgies from the period before, during, and after the Reformation” because the multiplicity of textual variants and editions made it nearly impossible to create a definitive list. In addition,

the problem is compounded by the sad state of the majority of copies, some surviving only as fragments rescued from bindings and others having undergone contemporary, near-contemporary, or modern mutilation and/or sophistication: “made-up” copies in every possible sense.

It seemed likely that ZSR’s books were among the many “made-up copies.”

After weighing the bibliographic evidence, I formed the following hypotheses:

- ZSR’s volume I and volume II are from two completely different editions of the Sarum breviary, rearranged and bound to look like a single publication.

- Volume I is a copy of the Hiemalis section of the 1556 Kingtson and Sutton edition whose title page went missing long ago.

- Volume II is the Estiualis section from the 1555 Caly edition that mistakenly included the colophon from a 1535 Paris edition. (It’s likely that the compositors—the people setting type—in Caly’s shop had used the 1535 Regnault edition as their source copy. Whether through carelessness or lack of facility with Latin, the compositor responsible for setting the final page had included the source copy’s colophon in the text of the new edition.)

- At some point a person in possession of both volumes had the title page from the Caly edition removed and placed at the beginning of the Kingston and Sutton volume I. Presumably the same person relocated a section page from the Caly edition to the beginning of volume II, to replace the title page that had been moved to volume I.

Most of the bibliographic evidence supported my hypotheses (but experts on Marian liturgical printing are welcome to weigh in with alternative theories!), so I felt confident enough to create catalog records for the volumes. But some mysteries remain, the most obvious being: why would someone go to the trouble of rearranging pages in the two books?

It’s possible that the rebinding and rearrangement were done early in the books’ 450-year history by an owner who actually used the volumes as liturgical books and wanted a uniform set. It’s much more likely that the alternations were a “modern mutilation and/or sophistication,” intended to make the volumes more attractive to a non-expert collector. Perhaps the moral of this story is that anyone setting out to collect early modern liturgical books should be able to translate Latin– at the very least, “caveat emptor.”

*For more information on 16th century English printers see: Peter W. M. Blayney, The Stationers’ Company and the Printers of London, 1501–1557 (Cambridge UP, 2013).

3 Comments on ‘Sarum Breviaries (1555, 1556)’

Fascinating! I think you should have new business cards made: Megan Mulder, Bibliosleuth. Also, I’ve never heard of velvet-bound volumes before; can’t say I’d want them myself…

Great post–love reading about your sleuthing!

As an expert on Marian liturgical printing, I agree with your findings. Seriously, very cool post!