This article is more than 5 years old.

How did a literary magazine from Wake Forest wind up in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology? Until recently, neither the Dibner Library nor Special Collections & Archives at Wake Forest University knew that it had.

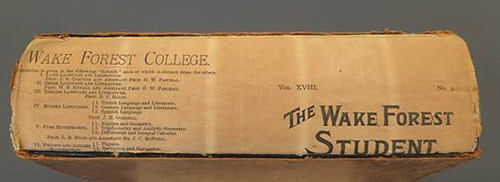

In a post on the Smithsonian Libraries Unbound blog, Vanessa Haight Smith (Head of Smithsonian Libraries’ Preservation Services) showcases instances of printer’s waste incorporated into book bindings — including an example of printer’s waste that we can identify as the front and back covers of an issue of the Wake Forest Student, the campus’s literary magazine.

Book bindings often incorporated printer’s waste. Binding structures require paper, scrap paper was often leftover from the printing process, and sometimes the same shop served as both a printer and a bindery. Unlike printer’s waste used as endpapers, Smith notes, “Waste used as spine linings is only visible when books are damaged in a way that exposes what lies underneath the covering.” In this case, the front cover and first section of text of the volume were detached, so the volume was sent to the Smithsonian Libraries’ Book Conservation Lab for treatment, and there the lining of its spine was revealed. What’s unusual and fun about this instance of printer’s waste is that we can tell exactly what it is — Volume 18, Issue 3 of the Wake Forest Student. Consequently, these scraps of printer’s waste provide tantalizingly specific clues as to the book’s provenance.

The book in question is the third volume of a later edition of the Mécanique céleste by French mathematician and astronomer Pierre Simon, marquis de Laplace. (View the item record in the Smithsonian Libraries’ catalog.) The Mécanique céleste translated Newton’s Principia from English into French and re-framed the Principia‘s understanding of classical mechanics from geometry to differential calculus, raising new scientific questions in the process. This particular edition of the Mécanique céleste is an English translation from the French original and was printed in four volumes from 1829–1839. So what can the appearance of the Wake Forest Student in its binding tell us about this particular copy of the Mécanique céleste?

To find out, I turned to the complete run of the Wake Forest Student — later titled simply The Student — held by the Special Collections & Archives here at Wake Forest. (View the item record in the ZSR Library Catalog.) The date of the issue was not visible in the binding waste itself, but by consulting our collections, we can date that particular issue to December 1898 and speculate that the copy of the Mécanique céleste now held by the Dibner Library was probably re-bound around the turn of the century. We may never find out what bindery had scraps of the Wake Forest Student lying around with which to line the spine of the Mécanique céleste now held by the Dibner Library. Perhaps the same shop that printed the Wake Forest Student also bound the Mécanique céleste, and perhaps that printer-bindery was located in or near Raleigh, NC since Wake Forest College was located in Wake Forest, NC at the time. Or to entertain a more fanciful supposition, perhaps the binder of the Mécanique céleste was a Wake Forest alumnus who received the Wake Forest Student on a subscription basis.

Even without identifying the specific bindery, however, we know more than we did before. Not bad for a day’s sleuthing!

8 Comments on ‘Beneath the binding of an astronomical treatise, scraps of a Wake Forest campus publication revealed’

This bit of biblio-sleuthing is terrific and fascinating from a preservation point of view. This week, I found similar binder’s waster underneath the endsheets of a German Bible — I love this stuff.

Interesting!

I can’t imagine why anyone would want to be anything but a librarian. So interesting!

very interesting

Whoa… the stories that a book can tell about where it’s been are sometimes more interesting than what’s in the book itself!

I love a good mystery! Thanks for sharing this.

Very interesting!

What a fascinating find! We should construct our own scenario complete with characters.