This article is more than 5 years old.

Book-making now-a-days, is done for money-making; and he who takes the Indian for his theme, and cannot go and see him, finds a poverty in his matter that naturally begets error, by grasping at every little tale that is brought or fabricated by their enemies. Such books are standards, because they are made for white man’s reading only; and herald the character of a people who never can disprove them. They answer the purpose for which they are written; and the poor Indian who has no redress, stands stigmatised and branded, as a murderous wretch and beast.

If the system of book-making and newspaper printing were in operation in the Indian country awhile, to herald the iniquities and horrible barbarities of white men in these Western regions, which now are sure to be overlooked; I venture to say, that chapters would soon be printed, which would sicken the reader to his heart, and set up the Indian, a fair and tolerable man.

George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indian (1841) vol. II, p. 8-9

ZSR Library’s first edition of Catlin’s Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indian (1841) is currently part of the exhibit George Catlin’s American Buffalo, on view at Reynolda House Museum of American Art through May 3, 2015.

In 1828 George Catlin was a struggling young artist in Philadelphia. Recently married, Catlin was trying to make a living as a portrait painter. But though Catlin was ambitious, he was not overwhelmingly talented. And painting portraits of wealthy New Englanders bored him; he preferred the more dramatic (but less commercially viable) history paintings.

At some point Catlin hit upon the idea of traveling west to paint American Indians of the great plains. He would later claim that this plan came to him as a sudden inspiration after he happened to see a group of Indian dignitaries in Philadelphia on their way to an official meeting in Washington. This anecdote may be fictional, but by 1830 Catlin was indeed headed west to St. Louis to seek the support of William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame), who had been appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

Clark took a liking to the young artist and invited him along on an expedition up the Mississippi to Fort Crawford, in what is now Wisconsin, for a council with representatives from several Indian nations. Catlin eagerly sketched and painted western landscapes and Indians in ceremonial dress. He had found his artistic calling.

Catlin’s timing was good, as there was growing interest in documenting the traditional life of American Indians, especially those groups living beyond the “civilized” eastern United States.

American artists and intellectuals in the early 19th century were obsessed with creating a distinctively national tradition in art and literature, independent of European influence. American Indians occupied an ambiguous position in this process. On the one hand, they were a unique and (to Europeans) exotic and interesting feature of the new world. They embodied the popular ideal of the “noble savage” – a concept associated with (though not invented by) French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who believed that Indians and other “primitive” peoples lived in harmony with nature and possessed inherent virtues that sophisticated Europeans had lost.

However, the Indians close at hand to most European-Americans did not fit neatly into this stereotype. The explanation, for Catlin and others, was that the Indians east of the Mississippi had been corrupted by contact with Europeans, their traditional society disrupted by disease, alcoholism, and government removal and containment policies. To find true, uncorrupted Indians, one had to go to the far west.

So in 1832 Catlin set out with his first expedition into, as he put it,

…the vast and pathless wilds which are familiarly denominated the great “Far West” of the North American Continent, with a light heart, inspired with an enthusiastic hope and reliance that I could meet and overcome all the hazards and privations of a life devoted to the production of a literal and graphic delineation of the living manners, customs, and character of an interesting race of people, who are rapidly passing away from the face of the earth— lending a hand to a dying nation, who have no historians or biographers of their own to portray with fidelity their native looks and history; thus snatching from a hasty oblivion what could be saved for the benefit of posterity, and perpetuating it, as a fair and just monument, to the memory of a truly lofty and noble race.

Catlin was highly critical of the U.S. government’s policy toward Indians. He felt certain that the Plains Indians would eventually suffer the same fate as their eastern counterparts, and he took seriously his role as chronicler of Indian civilization for future generations.

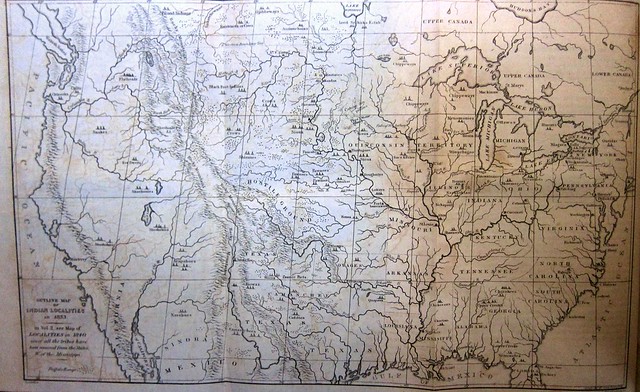

Catlin traveled throughout the western U.S. between 1830 and 1838. When he returned to the east, he had over 500 paintings and a collection of Indian artifacts. Catlin went on a lecture tour with his “Indian Gallery” and petitioned the U.S. government to purchase his collection and maintain it intact for public viewing. When Congress turned down his request, Catlin took his collection on a tour of Europe, hoping to raise interest and financial support for his work.

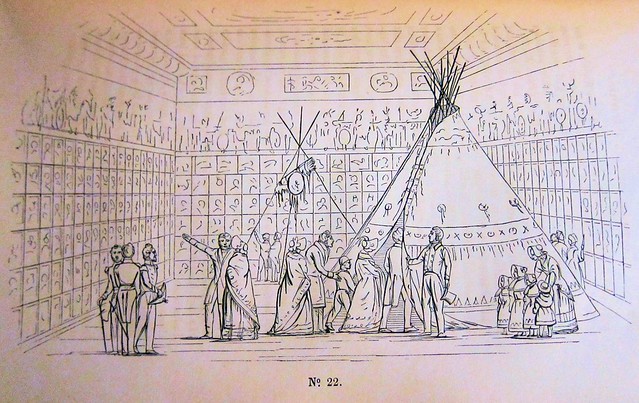

In addition to exhibiting the paintings and artifacts, Catlin accompanied a group of Ojibwa and Iowa Indians, who met various dignitaries and sometime staged performances at the exhibitions.

Catlin settled in London with his wife and young children, but he still found it difficult to earn a living through his lectures and exhibitions. So he returned to a project begun two years earlier: publishing a book based on his letters from his western journeys and illustrated with engravings from his paintings. He approached London publisher John Murray, who advised him to publish the book himself so that he could retain control over the contents and also keep all of the profits.

After an endorsement from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, Catlin was able to raise enough money to publish the books. But the process was arduous. Since he intended his book to be profusely illustrated with steel engravings, Catlin had to create over 300 illustrations based on his paintings. Even with two hired assistants, this was a considerable undertaking.

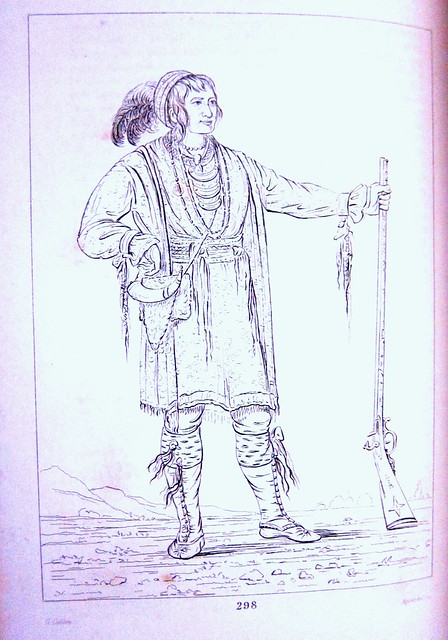

Finally in September 1841 the book was published. The two-volume Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indian included Catlin’s narrative of his travels (some of which had already been published in various American newspapers) interspersed with portraits, drawings of Indian artifacts, and views of western landscapes and fauna.

Catlin wrote to his father in November 1841

I have for 8 months past, been struggling against every obstacle, to get out my work, which was contracted to have been out in 3 months, & at last have got it before the world… I have just now began to circulate it and receive its avails, and a few weeks will decide how well I am to be paid. I sell the Book, since I have published, at £2.10, about 12 dollars per copy & the Am. Edition will be 8. Dollars. The commissions for selling are heavy and still my profits will be fair & considerable if I can give it an extensive sale, for which I must try hard. It has been reviewed in the most complimentary manner by the first Literary papers in London & consequently in the world.

The book did receive glowing reviews, especially from the English critics, and it sold well enough to recoup Catlin’s investment. American reviewers, though generally positive, sometimes took Catlin to task for inserting into his narrative too much moralizing about the mistreatment of Indians by the government. The Southern Literary Messenger, for example, concluded that Catlin “prefers savage to civilized life” and complained that “[O]ur country and its government… have been, and still are, perpetually assailed, by a spirit of mistaken philanthropy aggravated into fanaticism, as the stern, inflexible oppressors of the red man and the black man” [April 1845].

Catlin’s narrative is indeed a very personal and sometimes opinionated account of his travels and his interactions with Indians. He often takes the “civilized” world to task for its unthinking dismissal of Indian culture:

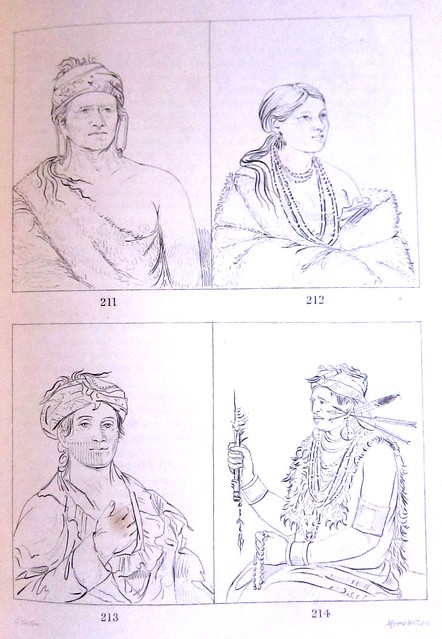

The civilised world look upon a group of Indians, in their classic dress, with their few and simple oddities, all of which have their moral or meaning, and laugh at them excessively, because they are not like ourselves— we ask, “why do the silly creatures wear such great bunches of quills on their heads?—Such loads and streaks of paint upon their bodies— and bear’s grease? abominable!” and a thousand other equally silly questions, without ever stopping to think that Nature taught them to do so— and that they all have some definite importance or meaning which an Indian could explain to us at once, if he were asked and felt disposed to do so— that each quill in his head stood, in the eyes of his whole tribe, as the symbol of an enemy who had fallen by his hand— that every streak of red paint covered a wound which he had got in honourable combat— and that the bear’s grease with which he carefully anoints his body every morning, from head to foot, cleanses and purifies the body, and protects his skin from the bite of mosquitoes, and at the same time preserves him from colds and coughs which are usually taken through the pores of the skin.

At the same time, an Indian looks among the civilised world, no doubt, with equal, if not much greater, astonishment, at our apparently, as well as really, ridiculous customs and fashions; but he laughs not, nor ridicules, nor questions,—for his natural good sense and good manners forbid him,—until he is reclining about the fireside of his wigwam companions, when he vents forth his just criticisms upon the learned world, who are a rich and just theme for Indian criticism and Indian gossip. I, 116

There is no doubt that Catlin genuinely hoped that his Gallery and his book would further the Indian cause among Europeans and European-Americans. But he also wanted them to make him rich and famous. As a result, the narrator of Notes and Letters sometimes comes off as an odd combination of amateur ethnologist and carnival huckster.

An example is Catlin’s account of painting the Mandan Mah-to-toh-pa’s portrait. Catlin begins with a detailed description of the warrior and his ceremonial dress:

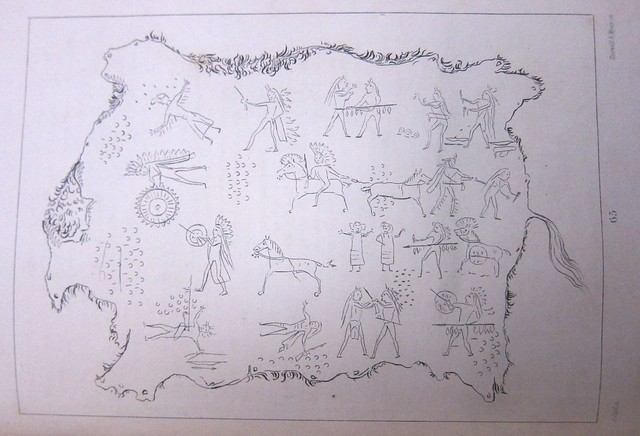

The next and second chief of the tribe, is Mah-to-toh-pa (the four bears). This extraordinary man, though second in office is undoubtedly the first and most popular man in the nation. Free, generous, elegant, and gentlemanly in his deportment— handsome, brave and valiant; wearing a robe on his back, with the history of his battles emblazoned on it; which would fill a book of themselves, if properly translated. . . .

Mah-to-toh-pa had agreed to stand before me for his portrait at an early hour of the next morning, and on that day I sat with my palette of colours prepared, and waited till twelve o’clock, before he could leave his toilette with feelings of satisfaction as to the propriety of his looks and the arrangement of his equipments… His dress, which was a very splendid in all its parts, and consisted of a shirt or tunic, head-dress, necklace, shield, bow and quiver, lance, pipe; robe, belt, and knife; medicine-bag, tomahawk, or po-ko-mo-kon. I, 164-65

Catlin provides several pages of description of every detail of Mah-to-toh-pa’s clothing and weapons. He explains the significance of many features, noting, for example that Mah-to-toh-pa is the only living member of the tribe afforded the great honor of wearing a headdress of buffalo horn. Catlin also describes in great detail the illustrations on Mah-to-toh-pa’s robe, which give a visual narrative of many feats of bravery.

Many artists before (and after) Catlin had depicted American Indian subjects. But most other 19th century artists produced generic and Europeanized portraits. Catlin’s depicts Mah-to-toh-pa and his many other subjects as unique individuals, with names and specific histories.

But Catlin also includes, here and elsewhere, a shameless plug for his Gallery:

The dress of Mah-to-toh-pa then, the greater part of which have represented in his full-length portrait, and which I describe, was purchased of him after I had painted his picture; and every article of it can be seen in my Indian Gallery by the side of the portrait, provided I succeed in getting them home to the civilised world without injury. I, 164

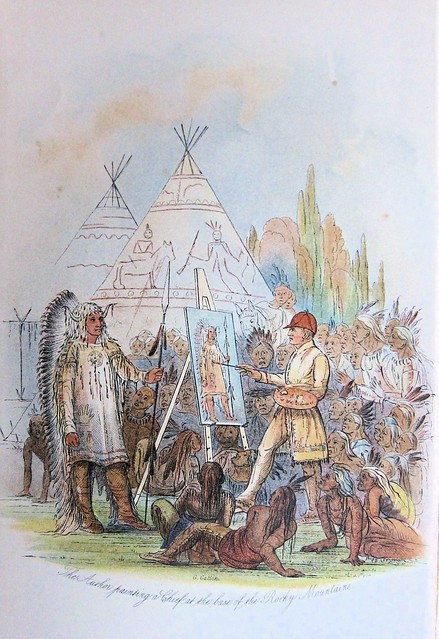

And he later reworked the incident into the highly fictionalized version depicted in the frontispiece above, which has the artist painting Mah-to-toh-pa’s portrait outside a tipi (a form of housing not used by the Mandans), surrounded by a throng of rapt Indians.

In addition to describing the people of the great plains, Catlin also gives an account of the landscape and wildlife he encountered. The great herds of buffalo feature prominently in his descriptions.

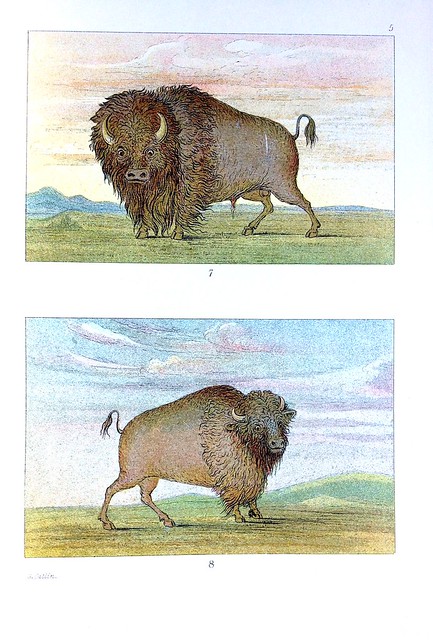

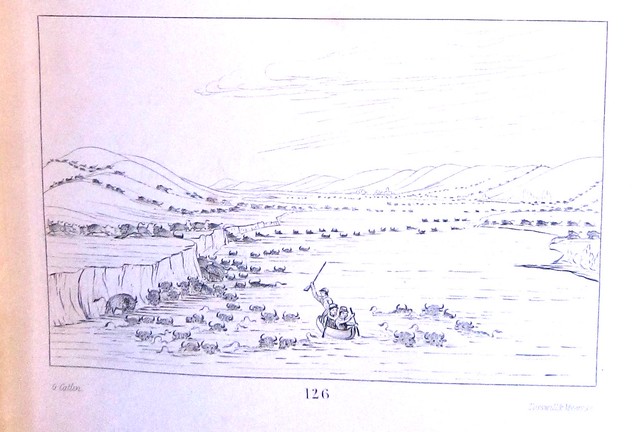

The buffalo bull is one of the most formidable and frightful looking animals in the world when excited to resistance; his long shaggy mane hangs in great profusion over his neck and shoulders, and often extends quite down to the ground (Fig. 7). The cow is less in stature, and less ferocious; though not much less wild and frightful in her appearance (Fig. 8). I,26

Like any good travel writer, Catlin played up the drama and adventure of his western travels. At one point he describes a close encounter with a large number of buffalo:

In one instance, near the mouth of White River, we met the most immense herd crossing the Missouri River— and from an imprudence got our boat into imminent danger amongst them, from which we were highly delighted to make our escape. It was in the midst of the “running season,” and we had heard the “roaring” (as it is called) of the herd when we were several miles from them. When we came in sight, we were actually terrified at the immense numbers that were streaming down the green hills on one side of the river, and galloping up and over the bluffs on the other. The river was filled, and in parts blackened, with their heads and horns, as they were swimming about, following up their objects, and making desperate battle whilst they were swimming. II, 15

Catlin understood the importance of the buffalo to the Plains Indians, and he was convinced that both the Indians and the buffalo would soon be extinct. He blamed fur traders in particular for spreading disease among the Indians and for decimating the population of buffalo and other western fauna.

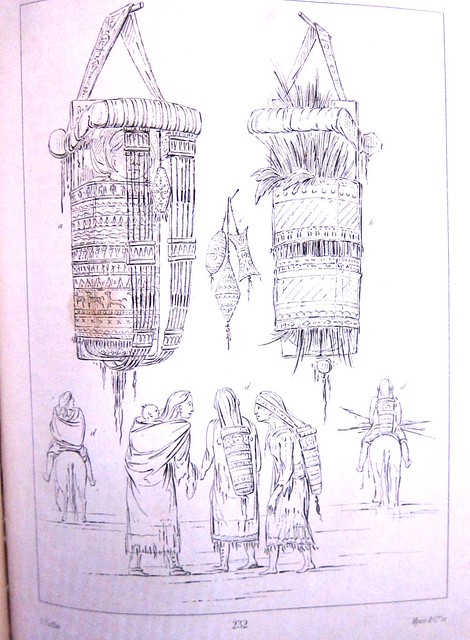

There are, by a fair calculation, more than 300,000 Indians, who are now subsisted on the flesh of the buffaloes, and by those animals supplied with all the luxuries of life which they desire, as they know of none others. The great variety of uses to which they convert the body and other parts of that animal, are almost incredible to the person who has not actually dwelt amongst these people, and closely studied their modes and customs. Every part of their flesh is converted into food, in one shape or another, and on it they entirely subsist. . . . .It seems hard and cruel (does it not?), that we civilised people with all the luxuries and comforts of the world about us, should be drawing from the backs of these useful animals the skins for our luxury, leaving their carcasses to be devoured by the wolves— that we should draw from that country, some 150 or 200,000 of their robes annually, the greater part of which are taken from animals that are killed expressly for the robe, at a season when the meat is not cured and preserved, and for each of which skins the Indian has received but a pint of whiskey! I, 295-96

Offending the fur trade lobby may have worked against Catlin when he again tried to sell his paintings to the U.S. government in 1852. His book had sold reasonably well, but had not generated enough money to keep him out of debt. And his beloved wife died suddenly in 1845, leaving him with small children to raise. At one point Catlin was thrown into debtor’s prison in London and had to be bailed out by his brother-in-law, who also took custody of his surviving children. In an attempt to raise funds, Catlin offered his paintings to the U.S. for a reduced price. Congress deliberated, but eventually refused to pay Catlin’s $25,000 asking price. Eventually the gallery was purchased by railroad tycoon Joseph Harrison, Jr.

Catlin published one more book, Rambles Among the Indians of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes, which gives anecdotes of his childhood encounters with Indians, his travels in the western United States, and a later journey to South America with only a freed slave named Caesar as his companion. (Some scholars doubt that he actually made the South American trip.)

Catlin ends this book with a warning that the spread of the telegraph and railroad into the western United States would cause the final destruction of the Indian peoples.

George Catlin died in 1872, at the age of 76. A few years later Joseph Harrison’s widow donated the paintings of his Indian Gallery to the Smithsonian, where they remain today. Fortunately, Catlin’s direst predictions did not come to pass. Indian civilization survived, even though the spread of European settlers and the industrial revolution had a major impact. But Catlin’s art and writings bear witness to a pivotal moment in American history– the early encounter between Europeans the Indians of North America.

5 Comments on ‘Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indian, by George Catlin (1841)’

What a great story! Thank you for showcasing this man and his work.

Megan, what a wonderful read! Thank you!

Such a wonderful exhibit and so glad we were able to participate!

It was wonderful to see how the collaboration between Reynolda House, the ZSR Library and the Museum of Anthropology informed the understanding of Catlin’s work.

Absolutely beautiful, Megan.