This article is more than 5 years old.

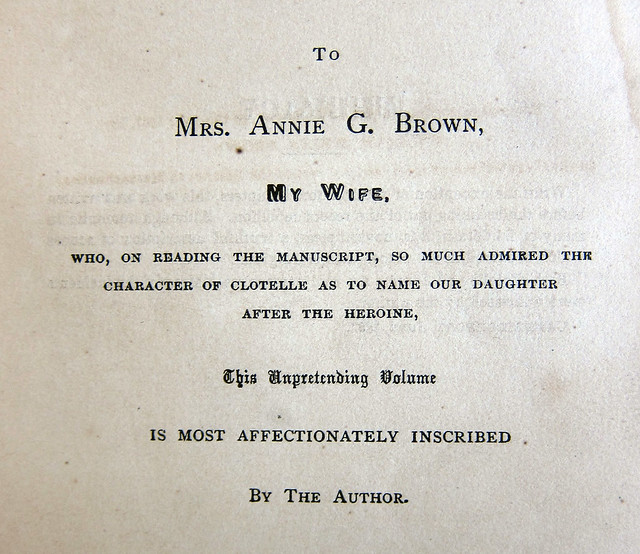

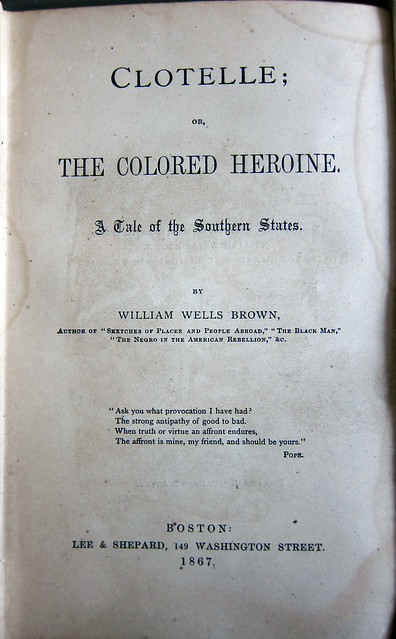

When William Wells Brown’s Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter appeared in London in 1853, it was the first novel ever published by an African American author. Brown’s novel was reissued four times over the next fifteen years, and with each edition the author made changes to the characters and the narrative. ZSR Special Collections recently purchased a copy of the 1867 edition, titled Clotelle; or, The Colored Heroine. This is the fourth and last version published and the only one in which the Civil War and its immediate aftermath are addressed.

William Wells Brown (1814-1884) was born in Kentucky to an enslaved woman named Elizabeth. His father was a white relative of his mother’s owner, Dr. John Young. The household soon relocated to St. Louis, and young William was put to work at various tasks. As was common practice, he was also rented out as temporary help to others, including a slave trader who regularly transported enslaved people down the Mississippi from St. Louis to New Orleans. It was from one of these voyages that William managed to escape in 1834. As he later recounted in his 1847 memoir Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, he made his way through Ohio and finally to freedom in Canada. William took his surnames from an Ohio Quaker man who assisted his escape.

By the 1840s Brown was living in New York and was active in the American abolitionist movement. He became a popular lecturer at anti-slavery meetings and in 1849 undertook a lecture tour of England. Reluctant to return home after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, Brown remained in England for several years. He had already published works of nonfiction, but the tremendous success of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (serialized in 1851 and published as a novel in 1852) inspired him to try his hand at fiction. The result was Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States.

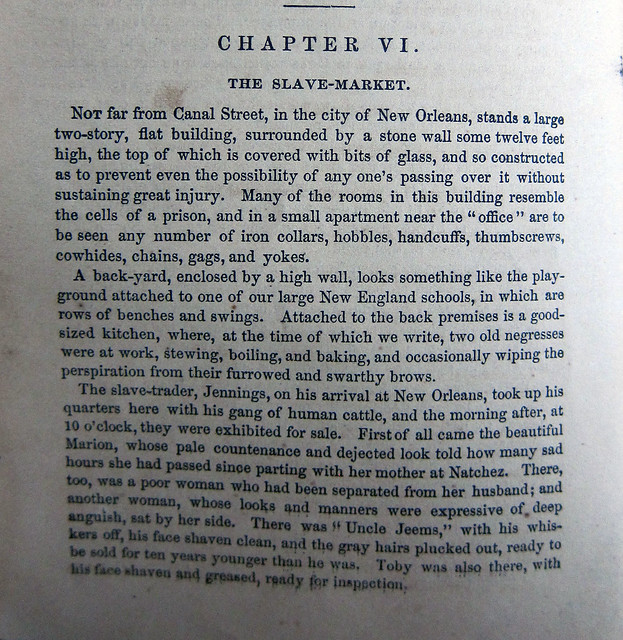

This original version, intended for an English audience, had as its starting point the persistent rumors that Thomas Jefferson had fathered the children of an enslaved Virginia woman. In this first Clotel Brown gives Jefferson two fictional daughters, both of whom are sold at the auction block. One of them is the Clotel of the title, who suffers various trials and eventually escapes her captors. But when Clotel returns to Virginia to rescue her still-enslaved daughter, she is set upon by slave-hunters. To avoid inevitable capture, she throws herself to her death in the Potomac River—just a few miles from where her indifferent father is absorbed in power and politics. As the book ends, however, Clotel’s daughter Mary manages to escape to freedom in France.

Brown’s narrative was not published in the U.S. until 1860, when it was serialized in the Anglo-African Magazine under the title Miralda; or, The Beautiful Quadroon. In 1864 a third edition titled Clotelle: A Tale of the Southern States appeared as part of abolitionist James Redpath’s Books for the Camp Fires series intended for Union soldiers. And finally in 1867 the last version, Clotelle; or, The Colored Heroine, was published as a novel by the mainstream Boston publishers Lee and Shepard.

The original Thomas Jefferson storyline is absent in all of the American editions. In the 1867 narrative, the title character Clotelle corresponds to the daughter Mary of the original novel. Clotelle is here the granddaughter of an enslaved woman who claimed that her father was an unnamed “American Senator.” Brown never made explicit the reason for this alteration in plot, but it is possible that he did not want the Jefferson controversy to overshadow his larger message, which was that slavery existed in large part because those men with the most power, influence, and moral credibility in U.S. society had refused to condemn it. As Brown states in his Preface to the first edition of Clotel,

Were it not for persons in high places owning slaves, and thereby giving the system a reputation, and especially professed Christians, Slavery would long since have been abolished. The influence of the great “honours the corruption, and chastisement doth therefore hide his head.” The great aim of the true friends of the slave should be to lay bare the institution, so that the gaze of the world may be upon it, and cause the wise, the prudent, and the pious to withdraw their support from it, and leave it to its own fate. It does the cause of emancipation but little good to cry out in tones of execration against the traders, the kidnappers, the hireling overseers, and brutal drivers, so long as nothing is said to fasten the guilt on those who move in a higher circle.

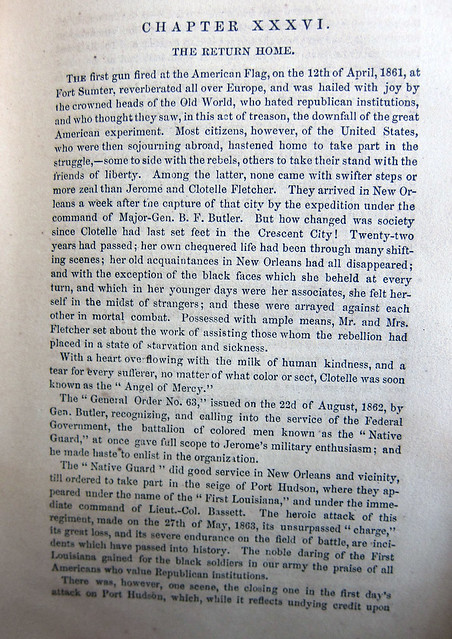

The 1867 Clotelle is in effect the first Civil War novel by an African American, as Brown added four short chapters at the end which detail his characters’ experiences during and immediately after the war. When war breaks out in 1861, Clotelle and her husband Jerome, also a fugitive slave, are living happily in Europe. They return to the U.S. to assist in the war effort, and Jerome is almost immediately killed in battle (in a fictionalized version of the Louisiana Native Guards at Port Hudson). Grief-stricken Clotelle becomes a volunteer nurse for the Union prisoners at Andersonville and aids in the escape of 96 men. She is imprisoned as a Union sympathizer but escapes with the help of her captors’ slaves, and she flees to New Orleans to wait out the end of the war. The novel closes after the war with Clotelle returning to Mississippi and purchasing the plantation on which she was once enslaved in order to open a school for freedmen.

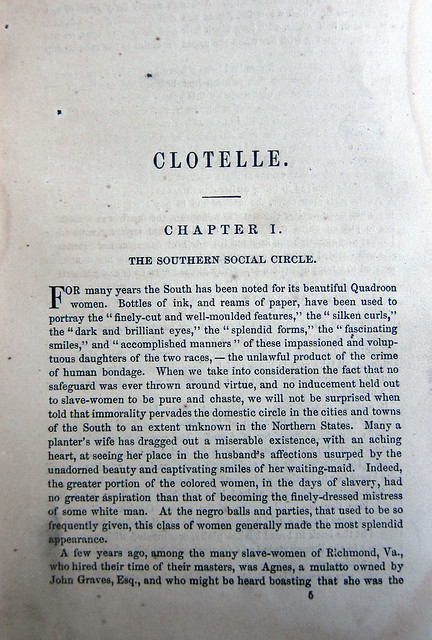

The 1867 Clotelle, like the previous versions, stuck closely to the standard formula for a 19th century sentimental novel. The plot is full of melodrama and improbable coincidences, and the female characters are all virtuous, beautiful, and very light-skinned (the term quadroon referred to a person with one black and three white grandparents). Later critics accused Brown of promoting stereotypes and currying favor with his white readers by making his heroines nearly white and conventionally beautiful. But the mixed racial heritage of Brown’s female characters also serves to highlight the hypocrisy of 19th century racial distinctions. The opening paragraph of Clotelle satirizes the sentimental depictions of mixed-race women:

For many years the South has been noted for its beautiful Quadroon women. Bottles of ink, and reams of paper, have been used to portray the “finely-cut and well-moulded features,” the “silken curls,” the “dark and brilliant eyes,” the “splendid forms,” the “fascinating smiles,” and “accomplished manners” of these impassioned and voluptuous daughters of the two races, — the unlawful product of the crime of human bondage.

Notwithstanding the fact that Brown himself is often guilty of such breathless descriptions, he nevertheless reminds his readers that these visions of loveliness are the product of a corrupt society that condones adultery and the sexual exploitation of enslaved women.

Many of the incidents in Clotelle are based on Brown’s own experience of slavery. And, as with many abolitionist writers of the time, one of his main goals is to debunk the notion that chattel slavery could ever be a benign institution. When Clotelle tries to convince her white father to free his enslaved workers, he argues that

I have always treated my slaves well… and my neighbors, too, are generally good men; for slavery in Virginia is not like slavery in the other States.

But Clotelle’s husband Jerome counters that

Their right to be free…is taken from them, and they have no security for their comfort, but the humanity and generosity of men, who have been trained to regard them not as brethren, but as mere property. Humanity and generosity are, at best, but poor guaranties for the protection of those who cannot assert their rights, and over whom the law throws no protection. [103]

All of Brown’s heroines are at some point under the protection of one kindly white man or another. But this protected position is never secure. When the women’s masters or lovers die, or leave, or suffer financial setbacks, the women and their children can suffer an enslaved person’s worst fate. The sudden reversals of fortune common in sentimental novels here serve to illustrate Brown’s point.

The first three versions of Clotelle were abolitionist novels, written to win readers over to the anti-slavery cause. So why did Brown and his publishers feel the need to issue yet another edition in 1867, after the war had been won?

The last Clotelle hints at some of the issues that Brown knew would face African Americans after the war. He recognized the urgent need for education of newly-freed African Americans, and the continuing hostility of many white Americans toward them. And as a historian, Brown also understood the vital importance of telling the stories of African Americans before, during, and after the war. The added chapters of the 1867 Clotelle also address the role of women in post-war society. Although Brown’s Clotelle is in many respects a typical heroine of the 19th century domestic novel, the last version of his book denies her the traditional happy ending of marriage and family. Instead she is forced to rely on her own resources to create a life of useful service for herself.

Many other authors would go on to describe the African American Civil War experience in works of fiction. But as the first of its kind, Brown’s novel in all its versions offers a fascinating glimpse into both the literary conventions and the political controversies of this pivotal era in American history.

____________________________

Selected Resources

Brown, William Wells and Robert S. Levine. Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States. Bedford Cultural Edition. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000.

Ann duCille. “Where in the World Is William Wells Brown? Thomas Jefferson, Sally Hemings, and the DNA of African American Literary History.” American Literary History, Vol. 12, No. 3, (Autumn, 2000), pp. 443-462. http://www.jstor.org/stable/490213

Jennifer James “ ‘Civil’ War Wounds: William Wells Brown, Violence, and the Domestic Narrative.” African American Review , Vol. 39, No. 1/2 (Spring – Summer, 2005), pp. 39-54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40033635

4 Comments on ‘Clotelle, by William Wells Brown (1867)’

Thanks Megan–so much more fascinating with the cultural background and context!

What an interesting tale. Thanks for doing the research, Megan.

That is a fascinating story. It is amazing what we have in our Special Collections, and the stories the stories tell.

You have a knack for uncovering the story of both famous and lesser-known books in our collection. You really make them come alive and fit into both historical and literary history.

These RBOM posts are always gems!