Freedom From, Freedom To

An Exploration of Free People of Color at Hephzibah Baptist

The population of free people of color in North Carolina grew by 604% between 1790 and 1860. Yet their stories are often relegated to footnotes or forgotten.

“Freedom From, Freedom To” is a digital history project that explores the lives of 21 free people of color who were members of Hephzibah Baptist Church in Wake County, North Carolina.

Introduction

Free people of color held a unique place in pre-emancipation society. In many ways, they had more freedom than enslaved individuals. They could own property, marry freely, seek out education, and work for wages. However, freedom was a tenuous state and constantly challenged. In 1830 the “Free Negro Code” was passed to control movements and activities of free people of color. Restriction on free people’s actions became so limited that by the end of the 1850s, it was illegal for them to own guns or dogs.

Despite holding this extraordinary position in society, free people of color are often absent from the historical record. Low literacy rates, lack of census data, and at times the intentional obscuring of records can make it difficult to understand what life was like for specific free people of color. Hephzibah Baptist Church’s minute book – which recorded information like when people joined and left the church, the names of committee members, and details of excommunications – can help fill this archival gap.1

Religious Expression

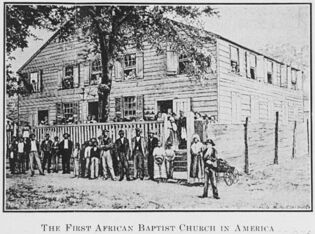

With evangelicalism on the rise in 19th-century America, religion became an integral part of everyday life. The church was a space where people formed community and built their own personal identity based on Baptist beliefs that only God can pass judgments on one’s morality and that one can achieve salvation through faith alone.

Because these spaces were so integral to one’s existence – their understanding of themselves and the world around them – it was incredibly impactful that free people of color were able to chose how, where, and with whom they practiced religion. As opposed to enslaved individuals who were often forced to participate in whatever religion their enslavers deemed appropriate, free people were able to determine what religion spoke most directly to them.2

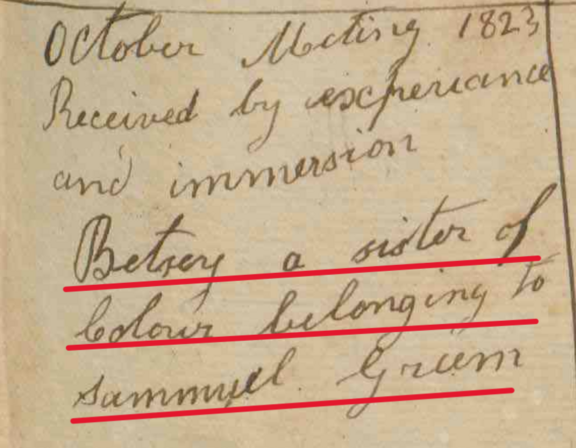

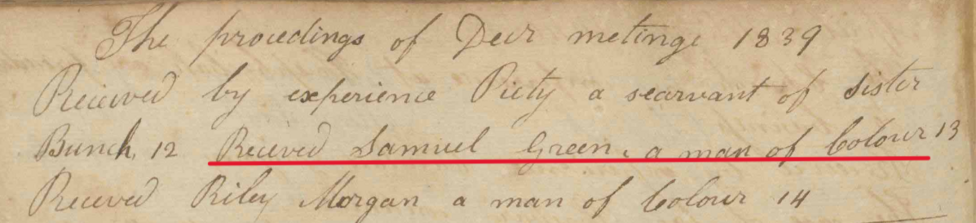

The story of Sammuel Green and Betsey exemplifies the power of choice in religious expression. Both Sammuel Green and Betsey are listed in the Hephzibah church book as people of color. However, Sammuel was a free man of color who enslaved Betsey. While Betsey may have chosen to join the church on her own, it is also possible Sammuel ordered her to. When Sammuel joined the church over a decade later, he almost certainly did so of his own fruition.

Community Building

Free people of color’s lives were frequently impacted by the fear of white individuals. The impact of white fear is seen clearly in the isolation freedmen faced. On the one hand, free people of color were not allowed to integrate with white communities due to the belief that they were still racially inferior. On the other, they were not permitted to interact with the enslaved population for fear of inciting uprisings. Even gatherings of only free people of color were looked at with suspicion as many white people believed doing so would lead to the promotion of emancipation.3

Gatherings at church were one of the few spaces where these societal expectations were less strictly enforced. In the Hephzibah church book, we see white and free people of color both being referred to as “brothers” and “sisters”. This was a term of respect that signaled a more equal footing between each group within the context of the church. Additionally, based on the writings of the church book, it appears enslaved individuals were able to attend church services and meetings. This would have allowed the free people of color who were also present at these events to interact with groups from a similar cultural background and lived experiences.

Additionally, the church book seems to include multiple families of free people of color. By joining the same church community, these families were able to come and spend time together frequently while circumventing the suspicion that they usually faced when gathering. On pages 127 and 128 of the church book, you can see several Morgans and Smiths listed amongst the free members of the church.4

Under Surveillance

While free people of color who were members of the church were afforded certain liberties like those listed above, they were still controlled by the white people around them. The main avenue for this was church-sanctioned citations. Members of the church could be cited for infractions ranging from missing meetings to adultery. There are even instances of members receiving citations for dancing or “fiddling”. All members of the church – white, free, and enslaved – were cited. There are even instances of enslaved church members citing other members of the church providing them with a level of power in the community. However, members of color were more likely to be excommunicated without due process and faced more barriers to rejoining the church. Being removed from the church would have been a devastating punishment that severed an individual from the belief system and community and, for free people of color, would have given them the difficult task of finding another church that would accept them.5

We see free people of color in the church book most often when they receive citations due to the intensity of surveillance.

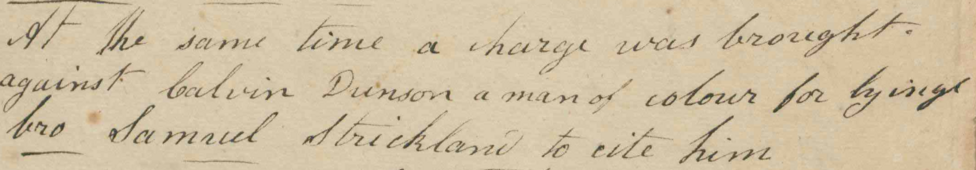

In 1845, six years after joining the church, Calvin Dunston was charged with lying. After being visited by a white male member of the church he was excommunicated. Census listings show that Calvin then moved to Randolph County where he lived for the rest of his life.6

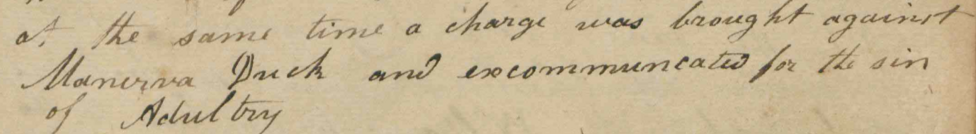

Minerva Duck was a female member of the church who was charged with adultery in 1844. Whereas Calvin was cited, visited by another member of the church, and then excommunicated months later, Minerva was cited and excommunicated at the same time. Census records show that in 1850 a woman named “Minervy Duck” was listed in Wake County along with a six-year-old boy named Andrew Duck. If this is the same woman, it is likely that Andrew was born out of wedlock as a result of the adultery for which Minerva was excommunicated.7

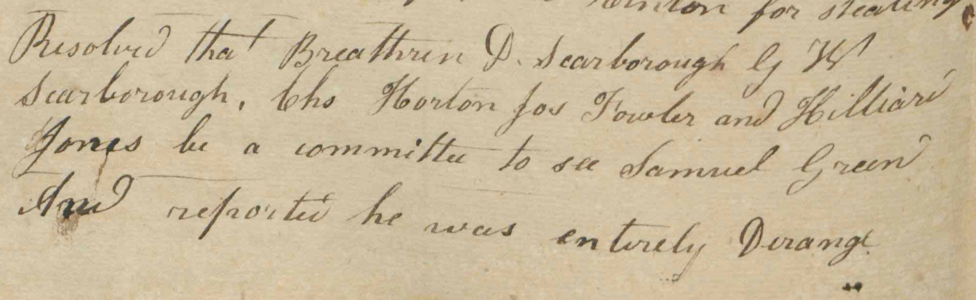

Sammuel Green, who was mentioned in the section on religious expression, also faced surveillance within the church. It is unclear what charge Sammuel faced, but it was serious enough that a committee of five white male members of the church was sent to visit him. While he was not excommunicated, the committee reported to the church that Sammuel was “entirely deranged.” This declaration could have had a number of causes from actual mental illness to abolitionist sentiment. Either way, Sammuel’s citation shows that despite his assimilation to his white counterparts through his participation in slavery, he was still faced with the same scrutiny as other free members of the church.

Conclusion

The church book provides us with a glimpse into what life was like for free people of color during this time. However, additional primary source analysis often falls short at expanding what we know about their stories. Documents like personal accounts, wills, and marriage records don’t exist in the same way they did for white people during this time because of this liminal existence free people of color occupied. While they were free from slavery, they were not free to move through the world without facing discrimination.

You can help uncover their stories by visiting From The Page and contributing to our efforts to transcribe documents like the Hephzibah Church Book and more.

Acknowledgements

This exhibit was created to explore the intersection of religion, race, and freedom in antebellum North Carolina. It also serves to highlight Wake Forest University’s special collection and teach audiences about primary source archival research.

This exhibit was created by Mary Kate Mauney for her Master’s capstone with the University of North Carolina Greensboro’s Public History Program. Special thanks to Rebecca May with Wake Forest’s Special Collections and Dana Logan with UNCG’s Religious Studies Program.

Footnotes

- To learn more about how church books can be used as an archival resource, see On Jordan’s Stormy Banks: Evangelicalism in Mississippi, 1773-1876 by Randy J. Sparks.

- For an analysis of the intersection between race and religion at this time, see Masters and Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 1740-1870 edited by John B. Boles.

- For more information on what daily life was like and what restrictions free people of color faced, see The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860 by John Hope Franklin and North Carolina’s Free People of Color, 1715-1885 by Warren E. Milteer Jr.

- From 1824 to 1849 there were 6 members of the church with the last name “Morgan”. Their names were Riley, Milley, Zelphy, Solomon, Brian, and Peggy. In 1839, two women named Mary and Pethyanne Smith were accepted into the church. In 1843 two more Smith women, named Susan and Pelsey, joined.

- Baptists in America by Bill J. Leonard explores how church books and their recording of disciplinary cases provide unique information about religious life for people of color at this time.

- This 1870 census for Randolph County lists Calvin Dunson as head of the household along with his wife, Nancy, and their children. Given the age listed for Calvin and his designation as a free man of color, it appears this is the same man who was a member of the Hephzibah church. It would not have been uncommon for individuals who were excommunicated to move to other areas where they could have a fresh start.

- This 1850 census for Wake County lists Minerva Duck as head of household and a free woman of color, along with a young mixed-race boy named Andrew Duck. Given her age and designation as a free woman of color, it appears this is the same woman who was a member of Hephzibah church. It is also likely that Andrew was the result of the adultery for which Minerva was excommunicated. It is somewhat surprising that Minerva was cited and excommunicated on the same day, as usually the church took about a month between citations and decisions. However, given that Andrew is listed as mixed race, this could mean that Minerva had an interracial affair, which would have been looked on as a grievous offense and would have been punished quickly.