This article is more than 5 years old.

You asked me to tell you about my theory of poetry. Really I haven’t got one. I like things that are difficult to write and difficult to understand; I like “redeeming the contraries” with secretive images; I like contradicting my images, saying two things at once in one word, four in two words and one in six. But what I like isn’t a theory, even if I do stabilize into dogma my own personal affections.

Dylan Thomas to Charles Fisher, 1935. In The Collected Letters of Dylan Thomas, ed. Paul Ferris (London: J.M. Dent, 1985), 208.

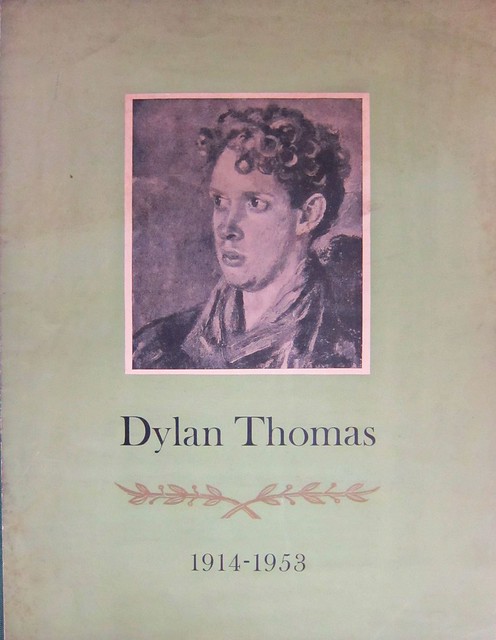

Dylan Thomas, who was born 100 years ago this week, was 20 years old when he wrote of his non-theory of poetry. He had just moved from Swansea, his childhood home, to London. His first volume of poetry had been published in December 1934 and was starting to attract critical notice.

By the time Thomas died less than two decades later he was Wales’s best known literary figure. But “difficult to write and difficult to understand” is an apt description of Thomas’s life as well as his writing.

In March of 1934 Dylan Thomas was still living at his parents’ home in Swansea. He was already a prolific poet, and a few of his poems had recently been published in literary magazines. When fellow Welshman Glyn Jones wrote to inquire about his background, Thomas replied thusly

I am in the very early twenties. I was self-educated at the local Grammar School where I did no work at all and failed all examinations. I did not go to a university. I am not unemployed for the reason that I have never been employed. I have done nothing but write, though it is only recently that I have tried to have some things published. . . I believe I am going to live in London soon, but as, so far at least, no-one has offered me suitable employment, living is rather an ambiguous word. I shall probably manage to exist, and possibly to starve. Until quite recently there has been no need for me to do anything but sit, read and write (I have written a great deal, by the way), but now it is essential that I go out into the bleak and inhospitable world with my erotic manuscripts thrown over my shoulder in a sack. If you know any kind people who want a clean young man with a fairly extensive knowledge of morbid literature, a ready pen, and no responsibilities, do let me know. Oh, would the days of literary Patronage were back again!

Letters, 123

Soon after he wrote this missive, Thomas did manage to secure literary patronage of a sort. The Sunday Referee newspaper, which had published a few of his poems, awarded Thomas its Poet’s Corner Prize for 1934. The prize included the publication of a book of poetry.

However, the Referee editor Victor Neuburg had some difficulty securing a publisher for a 19-year-old unknown poet. The publication was delayed for months, which gave Thomas time to worry over his selections. He wrote to fellow Referee poet Pamela Hansford Johnson in May 1934 about his process of choosing and revising poems to include in the book:

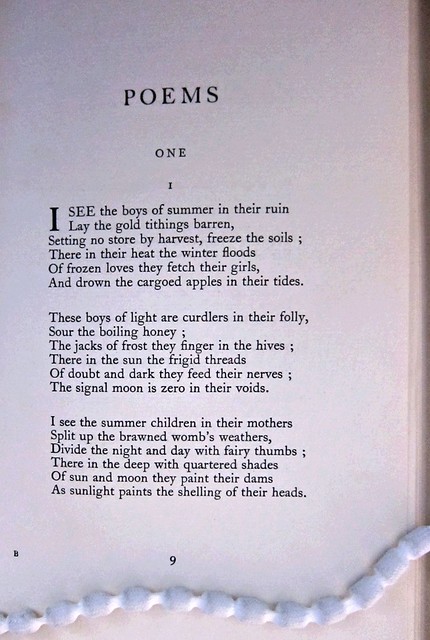

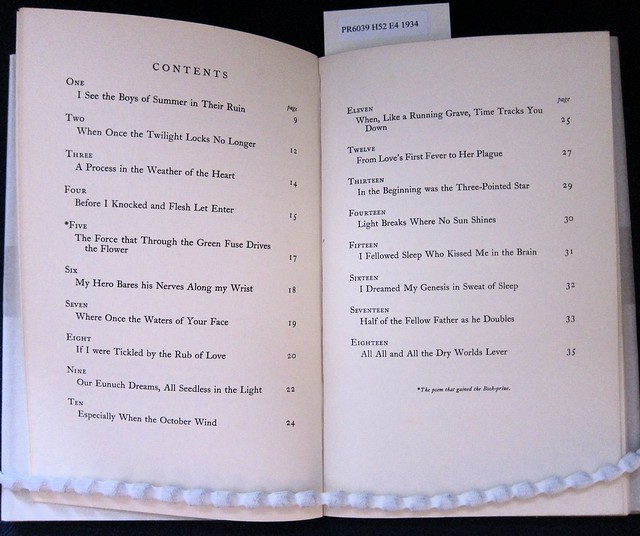

I am going to include some poems which have been printed, so “Boys of Summer”, though altered & double the length, is to open the book. Other poems are:

“Light Breaks Where No Sun Shines”. “Before I Knocked And Flesh Let Enter”. “No Food Suffices” (revised). “When Once The Twilight Locks” (revised). “Our Eunuch Dreams”. “A Process In the Weather”. “The Force that through the Green Fuse”. “Where Once the Waters of Your Face”. “That The Sum Sanity” (revised). “Not Forever Shall the Lord of the Red Hail” (revised). And about six or seven others I am still in the process of pruning and cutting about. You say Vicky’s [i.e., Victor Neuburg] obstinate. Well you know I am, too. And nothing that I don’t want goes in.

Letters, 151

In August he still working on his selections and was “glad that [Neuburg] hasn’t been able as yet to get my book published, for I want to cut some of the poems out & substitute some of the later ones.”(Letters, 189). By October he had lost faith in the whole enterprise:

My letters … demanded the return of my book. But I’m no more likely to get it than to find Gibbon’s History of Christianity in my navel. Only force remains. No, I can’t seriously adopt the idea of a second selection of even more immature & unsatisfactory poems. I find, after reading them through again, that the poems in Vicky’s confounded possession are a poor lot, on the whole, with many thin lines, unintentional comicalities, & much highfalutin nonsense expressed in a soft, a truly soft language. I’ve got to get nearer to the bones of words, & to a Matthew Arnold’s hell with the convention of meaning & sense.

Letters, 195

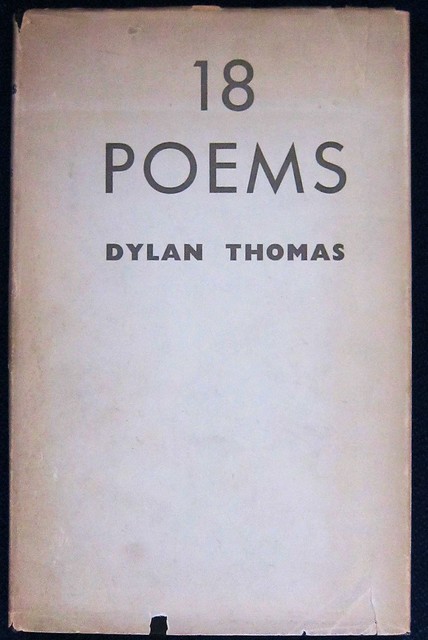

But Neuburg had finally found a publisher—David Archer of the Patron Bookshop– and Thomas’s first collection, titled 18 Poems, was published in December 1934 in a small edition of 250 copies.

The final selection of poems was different from Thomas’s original list, but it retained “Boys of Summer” as the opening piece.

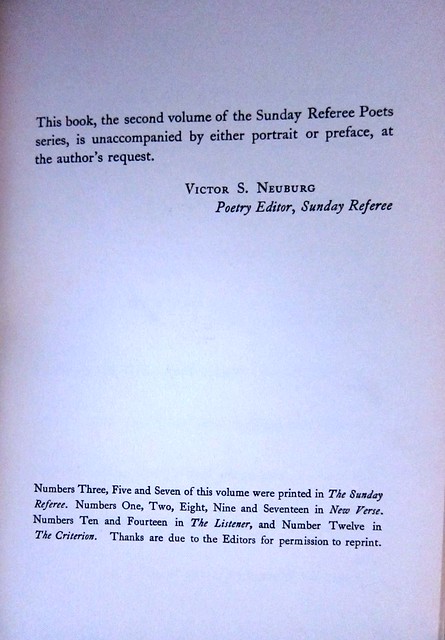

The book was a slender volume, unadorned with an author portrait or introduction, apparently at Thomas’s request.

Perhaps Thomas wanted to minimize Neuburg’s editorial commentary on the poems, since he had previously taken issue with his editor’s take on his poetry:

[L]ooking at Vicky’s noncommittal remarks about Dylan Thomas, the experimentalist, I found myself wondering who this sad-named poet was. . . . I’m not an experimentalist & never will be. I write in the only way I can write, & my warped, crabbed & cabinned stuff is not the result of theorizing but of pure incapability to express my needless tortuities in any other way. Vicky’s article was nonsense.

Letters, 160

18 Poems received several positive reviews in the winter and spring of 1935. The Times Literary Supplement was typical, observing in its brief notice that

Mr. Thomas’s idiom is certainly entirely his own, even if it is often too “private” to be easily intelligible. . . [But] the peculiar language in which these poems are written is easier to decipher than it at first appears, and Mr. Thomas’s habit of translating human experience into the terms of physiology or of the machine, and his vivid sense of the correspondence between the forces informing the macrocosm and the microcosm result in some powerful as well as surprising imaginative audacities.

TLS 14 March 1935, p. 163

Critics began to take notice of the young poet, and another collection, 25 Poems, was published in 1936. By the end of the decade, Thomas’s literary reputation was well established.

In addition to his poetry, Thomas also wrote stories, memoirs, novels, and plays. One of his most beloved works is his memoir A Child’s Christmas in Wales.

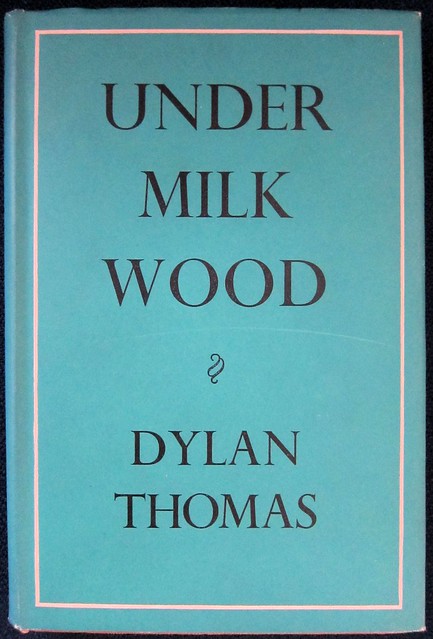

Another enduringly popular work is Under Milk Wood, a radio play that draws on Thomas’s early memories of growing up in Wales.

Under Milk Wood was first performed in 1953 at the Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y during one of Thomas’s tours of the United States.

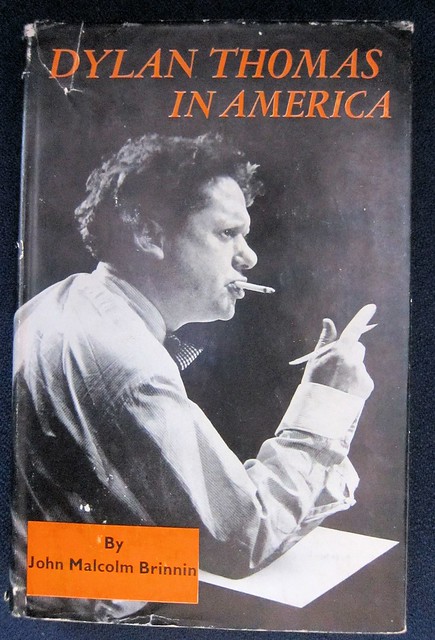

These tours, organized by the Poetry Center’s director John Brinnin, made Thomas wildly popular in American literary circles.

Thomas was a gifted speaker as well as a writer, and his readings drew large crowds wherever he went. But Thomas was also well known for his erratic and often irresponsible behavior. He was plagued by financial troubles, drank heavily, and had a volatile relationship with his wife Caitlin McNamara Thomas.

During the 1953 visit to New York, Thomas fell ill after a bout of drinking and died suddenly, aged only 39.

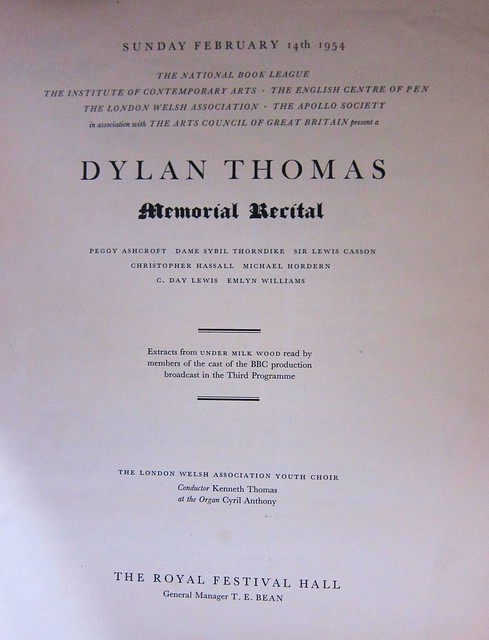

At his death, Thomas was memorialized as one of the most influential poets of the 20th century.

And now, on the centennial of his birth, Dylan Thomas is again remembered for his unique idiom and compelling imaginative language. The literary legacy that began with 18 Poems is poised to continue into a second century.