This article is more than 5 years old.

Senior Anna Hathcock, a student assistant in Special Collections and Archives who is often found at our reference desk, had some archives-related adventures on a research trip this summer. She graciously agreed to detail some bits about her trip and experience here, so read on!

This summer, I was in Stockholm, Sweden for 11 weeks conducting independent research through the Richter Grant. The main scope of my research centered on the continuous influence of Old Norse religion in modern day Scandinavia. I met with museum professionals, professors of religious studies, religious officials and archaeologists to build a working understanding of how Viking culture and religion has shaped Swedish contemporary identity.

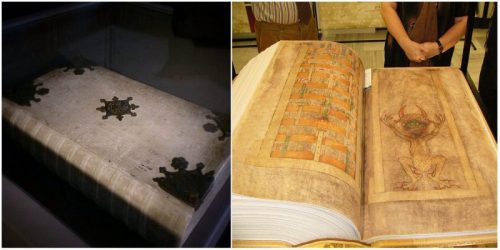

Additionally, because of my work in Special Collections and Archives, I sought to consult archival tools that would further tease out the relationships between Vikings and Early Christianity, such as Viking saga volumes or government decrees related to the Lutheran state-supported Church of Sweden. During my previous stays in Stockholm, I spent much of my time in the majestic libraries and reading rooms scattered throughout the city. I viewed breathtaking manuscripts, including Codex Gigas, also known as The Devil’s Bible, in Kungliga Biblioteket, thought to be the largest medieval manuscript in the world. Surely, I thought naively, ancient manuscripts encapsulating Viking-age sagas would be the most helpful archival items in my research endeavors.

I blindly set out on the quest to interact with these documents and quickly ran into some difficulties. To begin with, most of these manuscripts had been destroyed or lost in the past millennium. The few that remained were located in The British Library while I was located in Sweden, and furthermore, all of these manuscripts were written in either Old Icelandic, Old English, or Old Danish, none of which I am able to comprehend. To say I was disheartened was an understatement, but if I’ve learned one thing from working in archives, it’s that you might find the most helpful materials in unexpected places.

As I mentioned earlier, many of my days this summer were spent in museums, studying exhibits and meeting with curators and collections managers. Per usual, one day in mid June, I was perusing the collections at the Swedish History Museum in Karlaplan and I noticed an archival item in the Viking Age exhibit that caught my eye. It was a World War Two poster from 1943 when Germany occupied Norway. The poster depicted a Viking warrior and was intended to recruit Norwegian men to fight for the Nazi cause by appealing to the Nordic ancestral Viking identity. Surprisingly enough, this single poster was the archival crown jewel of my research. In the contemporary context, Viking ancestry is often celebrated by white supremacist, hate groups today in both Scandinavia and the U.S. Being able to trace this narrative to the 1940s through this single poster was a very powerful experience for me because it allowed me to connect the dots between the subject of my research, modern history, and world news today. That is the power of archives at play, especially when it comes to analyzing difficult or obscured histories.

One of SCA’s World War 1 posters (click on poster to see more, via the ZSR Flickr page)

This experience was also impactful for me because during my time in Special Collections and Archives last semester, I had the opportunity to assist on a project involving posters from the U.S. during World War 1. Though the contents of our poster collection here at ZSR are drastically different than the one that I observed at the Swedish History Museum, I was able to immediately connect both experiences due to their material similarities. When I saw the poster on exhibition in Sweden, I began to think of the preservation techniques invoked, of the hands that created the finding aids, and all of the minds that made decisions about the fate of this single poster in the past seventy years so that it could be used as an educational tool today. As much as I am fascinated with medieval vellum pages and leather volumes, I’ve learned that quite often, it’s the everyday archival material that has the greatest impact.

If you’re interested in learning more about my research and archival experiences this summer, be sure to visit Undergraduate Research Day in Z. Smith Reynolds Library from 3-5 pm tomorrow, Friday, September 28.

2 Comments on ‘Tales from Summer: Unexpected Encounters with “Common” Objects’

Thanks, Anna, for such a fascinating archives story!

Anna, thanks for this post! It’s fascinating to read how this poster connects so much of your research!