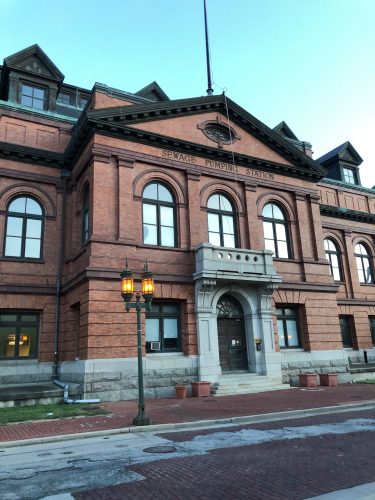

After 3 long years, I attended my first in-person national conference from June 5th to 8th in Baltimore, MD. The NASIG Conference (which focuses on scholarly communications, the information chain, electronic resources and serials) is my favorite conference to attend and it was good one to “break the seal” with, even though it was a bit different. The in-person attendance was about half what it was pre-pandemic (with about the same number of folks attending virtually). Also, while there was a fair amount of socializing, there was much less than in years past, as everyone was being a bit more cautious. Baltimore was a nice location and our hotel was right on the waterfront. I was surprised to find this building in the area, which turned out to be sewage pumping station. I would hazard a guess that it’s one of the best looking sewage pumping stations in the U.S.

Rather than give you a little bit of info on a bunch of sessions, I’m going to focus on just one, because it was very dense, and will take a while to summarize. The session I’m going to focus on is the keynote address “What Does the Transition from Publishing to Data Analytics Mean for Libraries?” by Sarah Lamdan, a librarian and law professor from the City University of New York Law School. She began by asserting that all of our library vendors are moving to Data Analytics. What is Data Analytics? It is the pursuit of extracting meaning from raw data using specialized computer systems. The systems transform, organize, and model the data to draw conclusions and identify patterns. Data Analytics (DA) companies sell a variety of DA products, including:

- “Business solutions” – telling businesses what to do

- “Risk assessment” – assessing how “risky” someone or something is

- “Metrics” – assessing “impact”

- “Competitive intelligence” – compiling and sorting data about competitors/consumers

- “____ Insights” – using data to build more information

- “Predictive _____” – using data to predict events (this one is creepy)

In more concrete terms, these sorts of products would be things like academic metrics, Covid-19 projections, stock market predictions, or predictive policing (this is where the predictive stuff gets creepy).

Publishing is quite different from Data Analytics:

- Printing and selling finalized materials (Publishing) vs. Selling raw data, structured information (including published materials), and DA products (Data Analytics)

- Transaction ends at point of sale (Publishing) vs. Transaction is continuous and incomplete (licensing, streaming, platform-based) (Data Analytics)

- No secondary data market (Publishing) vs. Many secondary data markets (Data Analytics)

- Libraries/readers are main consumers (Publishing) vs. Libraries/readers are among many customers (Data Analytics)

Why should we care about this? Well, the large publishing companies that libraries regularly deal with are being reclassified as Data Analytics companies. These include RELX Group (the new conglomeration of Reed Elsevier Lexis-Nexis), WestLaw, and Clarivate, which recently acquired ProQuest and its numerous subsidiaries.

Clarivate created a Data Business Value Pyramid, which shows how they make profit at every level. The levels are, from the bottom up:

- Raw Data

- Smart Data

- Platform

- Predictive Analysis (i.e. what will happen)

- Proscriptive Analysis (i.e. what to do)

Or, in a more simplified manner:

- Data as a Service

- Information as a Service

- Answers as a Service

Lamdan argues that “answers as a service” is fraught and where a number of problems start to arise. The company RELX admits that their Data Analytics processes work so fast that they don’t even know what happens with their algorithms. Algorithms can be flawed or biased, which means the data they turn out can be flawed or biased. If the answers you’re getting from a DA company are based on flawed or biased data, the answers themselves may be flawed or biased.

All of this is a concern for libraries, because we depend on these companies and they have changed, in large part due to their Data Analytics practices. These changes include:

- Vendor consolidation (which means fewer choices for us, there are 2 major ILS/LSP vendors now, there were a dozen or so 20 years ago)

- Libraries are no longer their only/first priority customers

- Our data is seen as a resource (Companies are monetizing more and more of the research process, including pre-prints and analyzing the impact of articles)

- Our products are changing, getting predictive bells and whistles that we might not want

- Walled-garden platforms are different from open bookshelves

Data Analytics companies are getting into some creepy and civil rights infringing territory. RELX and Westlaw sold lots of data to ICE (Immigration & Customs Enforcement) in 2017. DA companies sell products to other law enforcement agencies, landlords, health care systems, insurance companies, banks, etc. This can lead to legal troubles, housing problems, etc. for individuals based on data that was processed in ways that DA companies themselves don’t understand and which may be biased or flawed. DA companies sell risk assessment information and can link things in data dossiers. When these companies promise that they “make the invisible visible” that means they expose stuff you want to keep private.

Lamdan boiled her concerns down to three major problem areas and offered solutions. The problems:

- Privacy problems – risk assessment and metrics full of personal data

- Access problems – paywalls

- Quality problems – less vetting and quality control as they focus on quantity

Potential solutions:

- Privacy problems – Get companies to promise to protect/expunge library data. Separating data brokering from research products.

- Access problems – Get companies to provide open/affordable options.

- Quality problems – Get companies to use profits from paywalls to invest in quality control and vetting, not just Data Analytics R&D.

While I appreciate the optimism embodied in Lamdan’s proposed solutions, I don’t share her hopefulness. My assessment is that if companies find a way to make a buck off something, they will never give it up.

Well, that’s enough from me. My report on next year’s NASIG Conference will be quite different because I have agreed to be the Co-Chair of the Conference Planning Committee (because, as I’ve said, I guess I don’t like myself).

6 Comments on ‘Steve at 2022 NASIG Conference in Baltimore’

Thanks, Steve, for this in-depth session description!

Conversations about the risks of data analytics being consolidated in the hands of the few – and overly mighty – are increasing in my circles as well. Glad to know you had such an in-depth keynote about it. Like you, I’m not optimistic about where things will go…

Thank you for sharing this, Steve. I’m aware of a clause to allow data analysis appearing in a library system contract as early as 15 years ago. It raised questions then and I think it raises even more now, as you’ve described.

This was really informative, Steve, thank you– I don’t know much about this, but now I want to learn more.

Important topic to discuss and take action on! Thanks for sharing, glad it was a good NASIG conference.

I think because of this post, this bit of news caught my eye — a “first ever top 100 brands report” from Clarivate: https://librarytechnology.org/pr/27480/clarivate-top-100-new-brands-report-reveals-trends-and-hotspots-in-rapidly-evolving-global-brand-landscape