My experience at the 2023 ALA Conference in Chicago was good overall, despite a series of narrowly averted disasters including: receiving zero notification that my booking to Chicago had been changed to a flight 4 hours earlier, which I had missed (luckily, I was able to get a re-booked flight that got me in 4 hours later than planned); a section meeting that I led that was in a hard-to-find hotel ballroom, plus there were no microphones, the hotel had the wrong meeting listed for our room and time, and there was a loud breakfast award presentation in the ballroom next door that ran over into our meeting time and we kept getting people from that meeting drifting into our room that we had to chase off, including a team of photographers (the meeting worked out okay in the end); and a Happy Hour where it took nearly an hour to get a drink (that was not a particularly happy hour, I must say).

Much of my time at ALA revolved around my role as the incoming Chair of the Metadata & Collections Section of Core, but I did attend some sessions that were very interesting. One of them was a panel discussion that was organized by the outgoing Chair of my Section on the metadata rights of libraries. This requires a little background: OCLC recently settled a lawsuit against Clarivate, seeking to stop Clarivate from using bibliographic records that were contributed by libraries to the OCLC cooperative database on the grounds that OCLC owns the copyright to member contributed records. Many librarians objected to this claim, of course. ICOLC (the International Coalition of Library Consortia) issued a strongly worded statement asserting that metadata created by libraries cannot be copyrighted by a third party. The Metadata & Collections Section of Core crafted a revised joint statement with ICOLC and is currently encouraging the whole of the Core Division to sign on to it. The panel discussion was around the issue of who owns the metadata created by libraries. The panelists included a practicing cataloger (Amanda Sprochi of the University of Missouri-Columbia), a library science professor (Karen Snow of Dominican University), a member of ICOLC who was involved in drafting the initial statement (Elijah Scott of the Florida Academic Library Services Cooperative), and a lawyer who is a copyright expert (Kyle Courtney, Harvard University). Sprochi argued that cataloging is a cooperative endeavor and always has been. In fact, the entire point of OCLC’s existence is to share metadata and make it easier on libraries (she said a book is the same in Washington as it is in Missouri, why not just use the same metadata?). She argued that catalogers generally believe that no one owns the catalog record, it’s there to be used and repurposed as necessary. Scott took a harder line, arguing the ICOLC position that any corporate entity that attempts to claim ownership of cooperatively created metadata does so against the interests of libraries and the public. Snow pointed to the Cataloging Code of Ethics which encourages collaboration to make standards and tools financially, intellectually and technologically accessible. Courtney discussed the legal aspects of the issue. He informed us that ideas, methods, recipes, data and facts cannot be copyrighted. So facts like the title of a book cannot be copyrighted. A work needs to have a creative aspect in order to be copyrighted, and, in as much as catalog records are almost entirely simply recitations of facts about a bibliographic entity, they cannot be copyrighted. OCLC claimed that by adding things like control numbers to records, they had added a creative component and could therefore copyright the records. Courtney pointed out that OCLC didn’t sue Clarivate for copyright infringement but for “tortious interference,” that is, inducing libraries to violate their contracts with OCLC. He further said that the fact that OCLC didn’t sue for copyright infringement is a giveaway that they weren’t sure about the strength of their own claims. Also, it’s a bad business idea to sue a paying customer. Sprochi said, as a cataloger, that there is some creativity to cataloging, but it’s constrained by a complex set of rules and guidelines. She said it’s kind of like painting by numbers, which I thought was a very apt metaphor. Scott brought the discussion around to first principles by asking why are we doing this work? It’s to make metadata findable and sharable, not to enrich one company over the other. Sprochi added that OCLC has a hard needle to thread. Either the metadata is open and shareable, which means even competitors can use it, or it’s not. It can’t be open and closed at the same time. The room was packed for the session and everybody stayed until the end. I now have a high bar to meet if I try to propose a session next year as Chair of the M&C Section.

Okay, I now realize I’ve already written a lot, so to be quick, I’ll just say that I also went to a very good session called “Small Team, Big Job: A Model for Sustainable Critical Cataloging and Reparative Description” by Melissa James, Marian Matyn, and Laura Thompson of Central Michigan University. In brief, they described how they developed a project to make changes to their catalog records from a DEI perspective. In this case, changing subject headings for “Indians” to use more accurate and inclusive language, such as using the names that native peoples have for themselves. We on the Resource Services Team have been wrestling with how to go about developing our own project along these lines and this presentation gave me several good, solid ideas for how we might proceed. That almost never happens at a conference presentation!

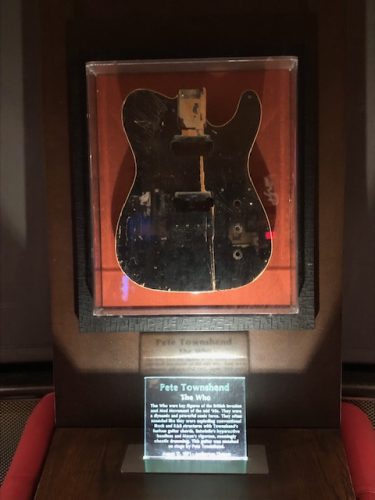

I didn’t really do anything in the way of sight-seeing in Chicago, but the Happy Hour that was kinda cranky for the first hour was held at the Hard Rock Cafe. Amongst the various bits of rock ‘n’ roll memorabilia, my favorite by far, as someone who’s first musical obsession was the Who, was this chunk of a guitar that Pete Townshend smashed in 1971.

One last note, the attendance at this year’s ALA was noticeably much higher than last year’s, which was the first back in-person. And the mood was much lighter, it felt like a normal ALA.

6 Comments on ‘Steve at ALA 2023’

The lawsuit stuff is really interesting, Steve! Thanks for sharing more about it.

Agreed, thanks for sharing – never considered how ownership of catalog records (or lack thereof) might be used or misused. Looking forward to hearing more about RS’ re-description work!

Thanks for your recap Steve. It is a very interesting about the question of whether catalog records are copyrightable. You did an excellent job of summarizing what must have been a complicated conversation.

Great post, Steve! Thanks for introducing us to the term “tortious interference” and the behind the scenes drama between OCLC and Clarivate. Thanks for supporting open access to catalog records!

Ooh, I’d’ve loved to be in the session about metadata ownership! I agree with Kyle (no surprise there: he and I go way back as copyright nerds!) and believe that over-assertion of rights by OCLC is problematic on a number of fronts. And yay for seeing smashed guitars!!

Good stuff to share — thanks, Steve!