This article is more than 5 years old.

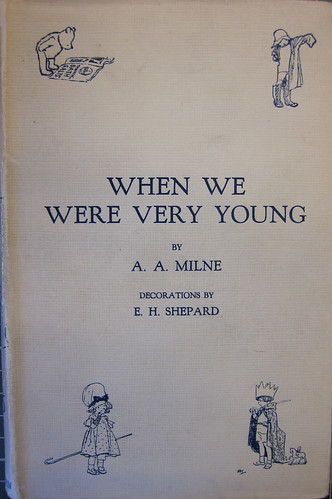

Alan Alexander Milne (1882-1956) never intended to be a children’s author. A former editor at Punch magazine, Milne was by 1924 a successful playwright and author of several volumes of essays and poetry for adults. When he announced to his editors (at Methuen in London and Dutton in New York) that his next manuscript was a book of children’s poems, they were skeptical. But When We Were Very Young was an immediate bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. The publishers reprinted the book four times in November and December of 1924.

Note from dust jacket flap, first edition

Note from dust jacket flap, first edition

Punch illustrator Ernest H. Shepard provided the “decorations.”

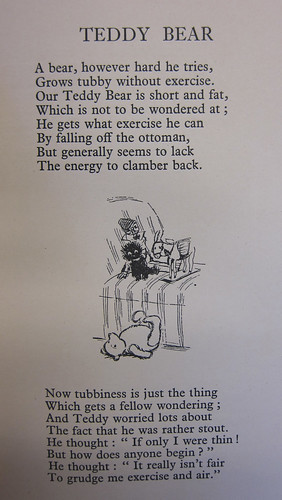

The bear who would become famous as Winnie-the-Pooh made his first appearance (as Edward Bear) in the poem “Teddy Bear.”

Milne took his craft seriously, observing that

The practice of no form of writing demands such a height of technical perfection as the writing of light verse. . . When We Were Very Young is not the work of a poet becoming playful, nor of a lover of children expressing his love, nor of a prose-writer knocking together a few jingles for the little ones, it is the work of a light-verse writer taking his job seriously even though he is taking it into the nursery.

Autobiography, 282

Although his English-nursery parlance can strike modern readers as a bit twee, Milne’s depiction of childhood is not sentimental. He later wrote that he sought to strike a balance between conveying the “artless beauty… innocent grace… [and] unstudied abandon of movement” of young children while also recognizing their “lack of moral quality, which expresses itself…in an egotism entirely ruthless” [Autobiography, 283].

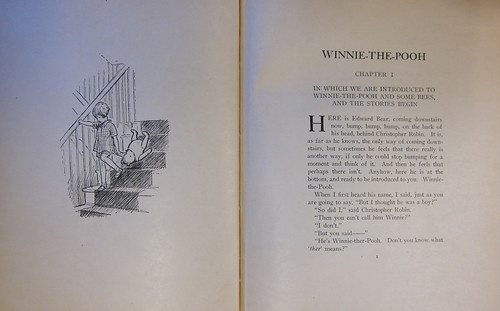

Two years later Milne brought out a volume of stories about Winnie-the-Pooh and other stuffed animals from the collection of his young son, Christopher Robin.

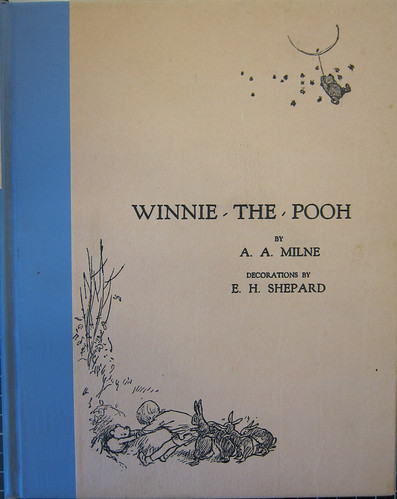

Title page from first American edition (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1926)

Title page from first American edition (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1926)

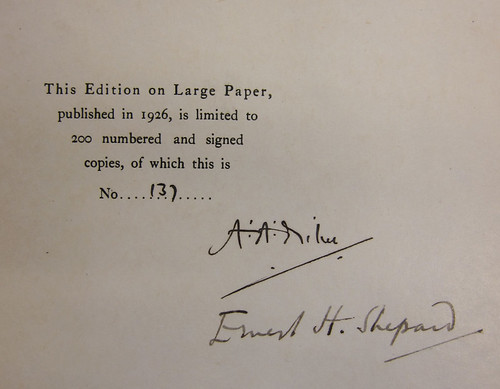

Milne’s publishers this time anticipated the demand for his book, and they ordered two sets of electrotype plates from which to print. The first American edition included 200 signed and numbered large-paper copies, of which Wake Forest’s is number 137.

The foibles of Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends Piglet, Eeyore, Owl, Rabbit, and Kanga and Roo were told with wry humor that captivated readers young and old. Milne later confirmed that all of the animals except for Rabbit and Owl were based on actual toys. The originals are still on view at the New York Public Library. The illustrations for Pooh, however, were actually based on a teddy bear named Growler, which belonged to Shepard’s son Graham.

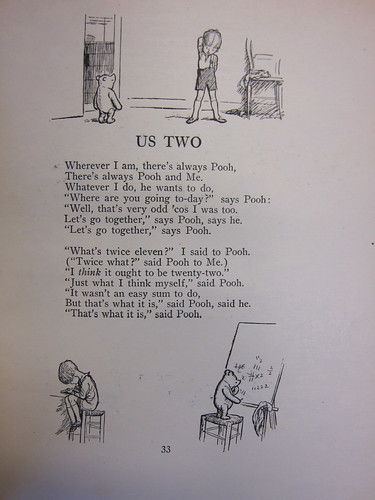

Winnie-the-Pooh was indeed wildly popular, and Milne followed it in 1927 with another book of verse, Now We Are Six. Pooh makes an appearance in one of the poems, “Us Two.”

From the first edition of Now We Are Six (London: Methuen & co., 1927)

From the first edition of Now We Are Six (London: Methuen & co., 1927)

The animals of the Hundred Acre Woods also appear in several illustrations.

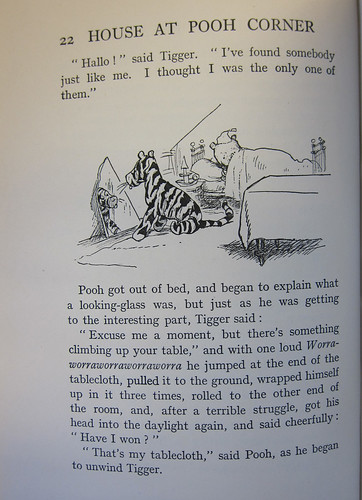

The next year Milne published another volume of stories about Pooh and friends, The House at Pooh Corner, which introduced the character of Tigger.

From the first edition of The House at Pooh Corner (London: Methuen & co., 1928)

From the first edition of The House at Pooh Corner (London: Methuen & co., 1928)

The House at Pooh Corner (1928) was Milne’s last work for children. He returned to writing plays, essays, and novels for adults. But none of Milne’s other writings approached anywhere near the popularity of Pooh. Literary critic Alison Lurie contemplated Pooh’s lasting renown on the fiftieth anniversary of Winnie-the-Pooh‘s publication, wondering “why this mild story about a group of English toys should have almost instantly become, and remained for 50 years, an international classic- probably the best-loved children’s book of the 20th century.” She concludes that

In spite of their apparent simplicity, “Winnie-the-Pooh” and its sequel, “The House at Pooh Corner,” tell a story with universal appeal to any child anywhere who finds himself, like most children, at a social disadvantage in the adult world. What Milne has done is to turn this world upside down, so that Christopher Robin becomes the responsible adult, while everyone around him has turned into toys or animals, inferior in both size and authority.

In later years Milne resented being pigeonholed as a children’s author.

I wrote four ‘Children’s books,’ containing altogether, I supposed, 70,000 words–the number of words in the average-length novel. Having said good-bye to all that in 70,000 words, knowing that as far as I was concerned the mode was outmoded, I gave up writing children’s books. I wanted to escape from them as I had once wanted to escape from Punch. . . . In vain. England expects the writer, like the cobbler, to stick to his last.

Autobiography, 286

Milne once complained that critics viewed all of his subsequent work through the lens of Pooh and Christopher Robin:

As a discerning critic pointed out: the hero of my latest play, God help it, was ‘just Christopher Robin grown up.’ So that even when I stop writing about children, I insist on writing about people who were children once.

Autobiography, 287

But Milne’s protests were indeed for naught. His children’s books, with their enduring appeal both for children and for people who were children once, have made Winnie-the-Pooh his legacy.

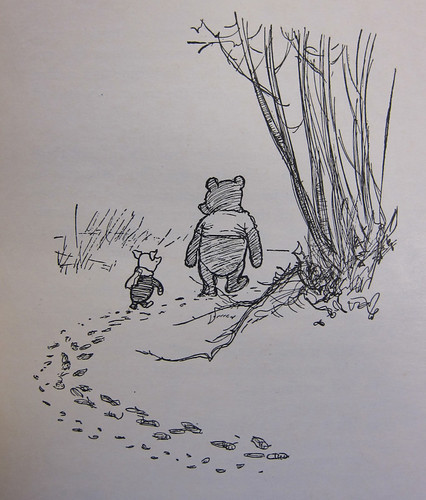

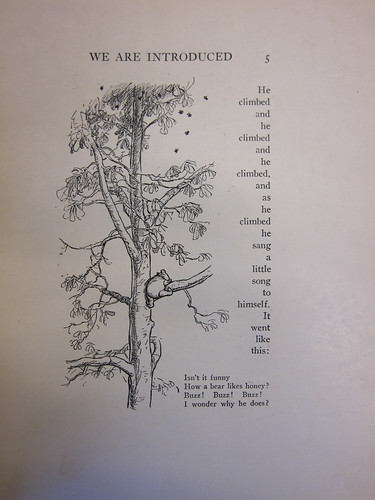

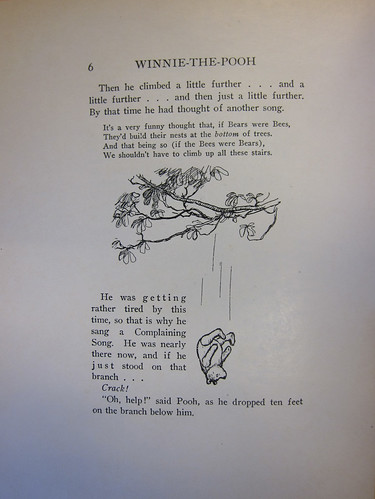

Illustration from the first edition of Winnie-the-Pooh

Illustration from the first edition of Winnie-the-Pooh

The books in Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s A.A. Milne collection were acquired from a variety of sources. The signed and numbered first edition of Winnie-the-Pooh was part of publisher Lynwood Giacomini’s collection, which was purchased by the library in 1976. When We Were Very Young came from the Charles Babcock collection and also has the bookplate of Dickens bibliographer John C. Eckel. Other volumes were purchased by the library.

References

Alison Lurie. “Back to Pooh Corner.” Children’s Literature 2 (1973): 11-17; “Now We Are Fifty.” New York Times Book Review (14 November 1976).

A. A. Milne. Autobiography. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1939.

John R. Payne. “Four Children’s Books by A. A. Milne.” Studies in Bibliography 23 (1970): 127-139.

6 Comments on ‘Winnie-the-Pooh, by A. A. Milne (1926)’

Excellent! I thought I noticed the copy in Preservation for repair was missing. I enjoyed reading your account of Milne-thanks.

Megan, what a great essay on Pooh in the ZSR collection. Thank you for bringing context to the works in the collection!

I loved Winnie the Pooh but never gave much thought to his author. Thanks for the post. It’s very interesting and is timely as Christmastime always brings out the child in us!

Great job. The writing and illustrations really do put a smile on your face. Thanks!

Such a delight! Thanks for featuring.

Thank you for sharing this. I have loved Winnie-the Pooh since my mother read it out loud to my 2 yr. old sister and I was 12 and listened in. Thank you also for sharing the link to the pictures of the “originals”.