This article is more than 5 years old.

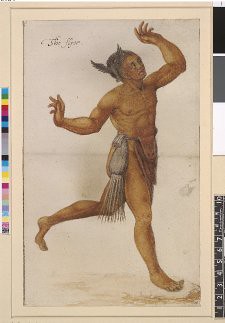

Secotan priest

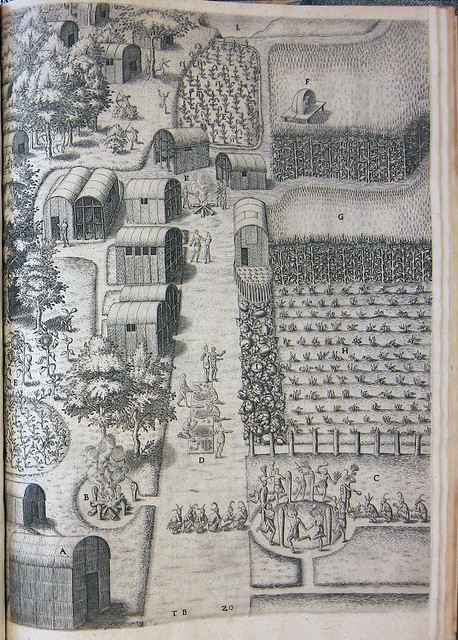

In 1590 the Frankfurt printer and engraver Theodor deBry published a folio edition of Thomas Hariot’s Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia with engraved illustrations based on John White’s watercolor paintings. DeBry’s engravings were the first images of indigenous North Americans that most 16th century Europeans had ever seen.

Thomas Hariot, a scientist, and John White, an artist and cartographer, had journeyed to North America in 1585 as part of Sir Walter Raleigh’s attempt to found an English colony in the new world. Hariot and White were charged with providing an accurate description, in words and images, of the geography, native peoples, and natural resources of the new world.

Raleigh and his associates wanted to encourage settlement in the Virginia colony in order to stake an English claim to compete with the Spanish and French conquests of much of North and South America. Accordingly, Hariot’s account emphasizes the abundant resources and generally friendly Indians that he encountered in Virginia.

John White created the first accurate map of the Virginia coast.He also painted watercolor images of the Indians he encountered, documenting their clothing and tools, religious and social rituals, agricultural methods, buildings, ships, and weapons.

Hariot and White returned to England in 1586 and delivered their accounts to the colony’s backers. In 1587 another group of English colonists set out for Roanoke, with John White as appointed governor of the colony. Also in this group were White’s daughter Eleanor and her husband Ananias Dare, future parents of Virginia Dare. The settlement did not fare well: food supplies ran low, and White was sent back to England for provisions the next autumn. When he finally returned in 1590 the Roanoke settlement had been abandoned and the colonists had disappeared.

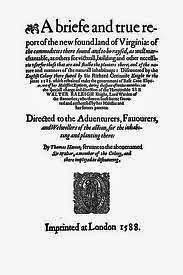

Meanwhile in England Thomas Hariot’s account of his experiences, titled A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, had been published as an individual quarto and as part of Richard Hakluyt’s extremely popular compendium of travel literature, Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589). Hakluyt’s book contained no illustations, however, and in 1590 he contracted with Theodor deBry, a skilled engraver and printer, to publish a deluxe volume of Hariot’s work along with illustrations based on White’s paintings.

DeBry’s edition was the first volume in a series of travel narratives —Collectiones Peregrinationum in Indiam Orientalem et Indiam Occidentalem (1590-1634)– for which he became famous. Accounts of European exploration and conquest of the Americas, Africa, and Asia were hugely popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. And DeBry’s Briefe and True Report has many features typical of the genre. Although ZSR’s copy is in Latin, DeBry also published editions in Hariot’s original English as well as Dutch, German, and French. Latin was still the language of international scholarship in 16th century Europe– but travel accounts were written by soldiers and adventurers, not academics. At the beginning of the century, nearly all printed material was in Latin; by 1600 a shift was underway toward publishing in the vernacular languages.

The 16th century also saw the beginnings of an empirical approach to science and history. Instead of relying on classical and church authority, naturalists and explorers recorded their first hand observations of the new lands and cultures they encountered. Thus the early modern travel narrative set itself in opposition to classical works of cosmography.

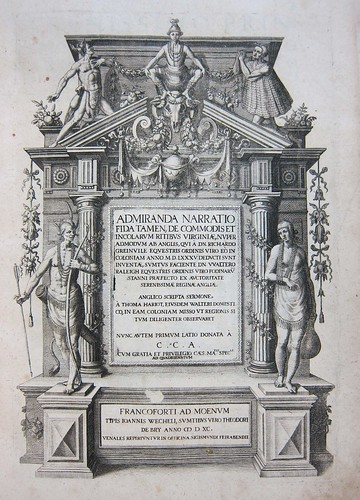

In many ways Thomas Hariot’s narrative and John White’s images typify this new approach. And deBry from his very title page makes it obvious that he is charting new territory. Instead of the classical figures who usually inhabited the ornate architecture on such pages, DeBry’s book features White’s Algonquian Indians. The new world literally replaces the old on the book’s first page.

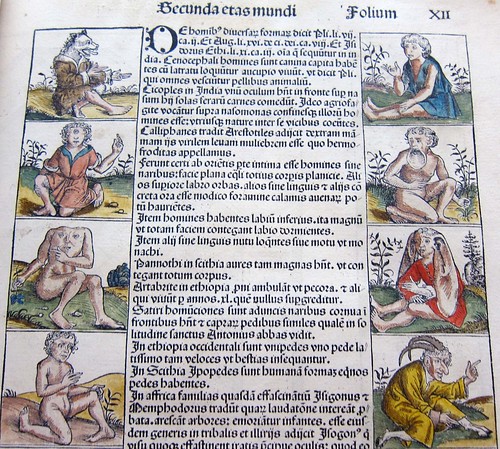

Despite the flood of firsthand travel narratives, 16th century Europeans were still influenced by the ideas of classical authors. In particular, images based on Pliny the Elder’s descriptions of the monstrous races from lands beyond the known world held firm sway over the imaginations of many Europeans.

John White and Theodor deBry’s Indians– exotic but dignified and definitely human– provided one of the first correctives to these mythical images.

DeBry’s engravings reproduce White’s paintings with reasonable accuracy. But a comparison of the paintings and engravings makes clear that deBry felt free to make some alterations. He added multiple perspectives to the depictions of several figures. He also filled in White’s spare backgrounds, and he altered the human figures, giving them more European facial features and the defined musculature typical of figural illustrations of the time.

DeBry also includes some additional images at the end of the volume–John White’s rather fanciful depiction of ancient Picts. For readers steeped in classical learning these images had obvious connotations: they were a reminder that for the Greek and Roman authors, the ancestors of deBry’s European readers were the barbarian races.

The 1590 first edition of this volume is part of the ZSR Special Collections Americana collection. These materials were purchased between 1938 and 1943 with matching funds from the Wake Forest College Board of Trustees and the Tracy W. MacGregor fund.

3 Comments on ‘A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590), by Theodor deBry, Thomas Hariot, and John White’

This is an excellent description of these materials, how and why they were made and a little art criticism as well. I really enjoy reading these accounts of our collections, knowing what their intended purpose was, and how they fit into the historical narrative. Thanks Megan!

Wow! Very interesting stuff. Thanks, Megan

It’s fun to discover all the magnificent materials we have in our collection!