This article is more than 5 years old.

E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, one of the most beloved children’s books of the 20th century, was first published 60 years ago this month.

Elwyn Brooks White (1899-1985) had a long career as a contributor and an editorial staff member at The New Yorker. He wrote poetry and novels for adults and was perhaps best known for his nonfiction essays. White had a lifelong affinity for animals and love of the natural world. He married New Yorker editor Katherine Angell in 1929 and soon after bought a farm in Maine. White’s keen observations on farm life in Charlotte’s Web and other writings were informed by his firsthand experience of life in the barnyard.

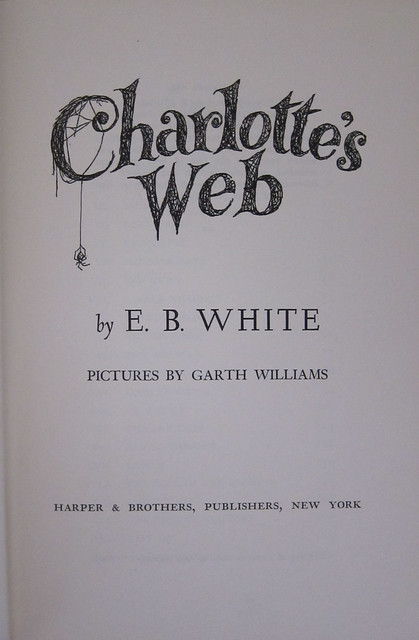

< Title page from ZSR Library’s copy of the 1952 first edition of Charlotte’s Web

Title page from ZSR Library’s copy of the 1952 first edition of Charlotte’s Web

White wrote three children’s books: Stuart Little (1945), Charlotte’s Web (1952), and The Trumpet of the Swan (1970).

Ursula Nordstrom was chief editor of the children’s book division at Harper and Brothers when E.B. White submitted the manuscript for Stuart Little. White was already well known by then for his pieces in The New Yorker and other literary magazines, and Nordrstrom later recalled that

Only another children’s book editor can know the emotions one has on hearing that a famous writer of adult books is going to send a book for children to the house, for talent in the former does not always carry over to the latter. And so it was with a certain relief that I read the manuscript and found that I adored it.

Stuart Little was published in 1945 to widespread (if not universal) acclaim. Some years later White delivered another manuscript to Nordstrom:

One day in the early spring of 1952 I was sitting in my Harper office and the receptionist came in to tell me E. B. White was outside. I went out to the elevator and greeted him, and he said, “I’ve brought you a new manuscript.” I hadn’t known he was even close to finishing a second book and I was overwhelmed. Thinking immediately that it was already pretty late to get it illustrated and printed and bound in time for the fall list, I said, “Have you given me a carbon copy too, so I can rush it off to Garth [Williams]?”

“No,” he said, “this is the only copy; I didn’t make a carbon copy.” And he gave me the only copy in existence of “Charlotte’s Web,” got back on the elevator and left.

An editor seldom has the luxury of enough time in the office to read manuscripts, but I decided I would have to give myself just that luxury that afternoon. There were no Xerox machines in 1952, and I didn’t dare take a chance on losing the manuscript on the train home, or whatever. So I sat down and began to read.

By the time she finished reading, Nordstrom recalled, “I knew that this was one of the great ones.”

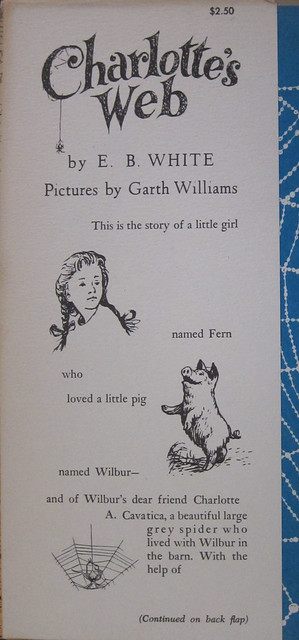

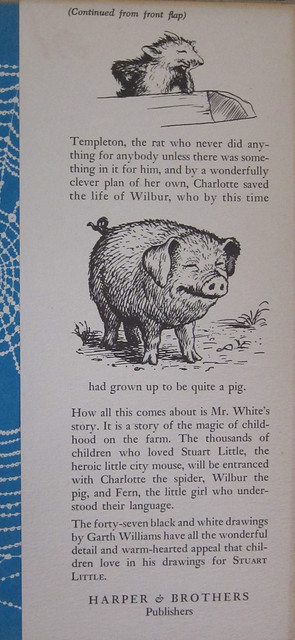

Dust jacket description from the first edition

Dust jacket description from the first edition

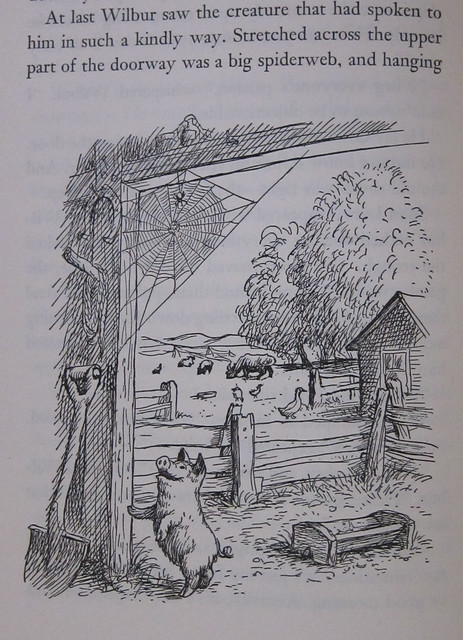

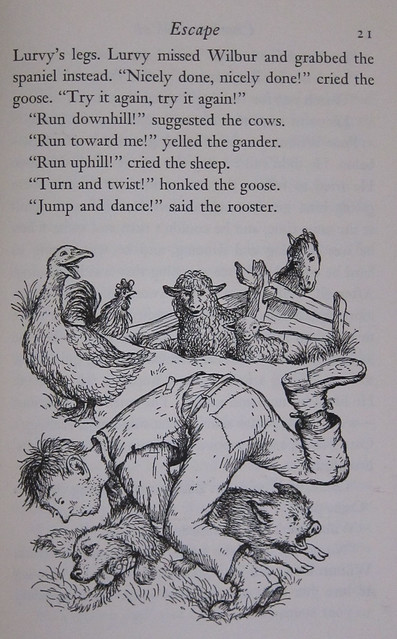

Part of the enduring appeal of Charlotte’s Web is White’s loving but entirely unsentimental depiction of farm life. The idea for the book grew out of White’s experiences on his own farm, in particular his attempt to save a dying pig, which he wrote about in a 1948 essay. The talking animals in Charlotte’s Web are funny and charming, but they exist in a real world where children grow up, friends die, and animals (including humans) kill and eat other animals to survive.

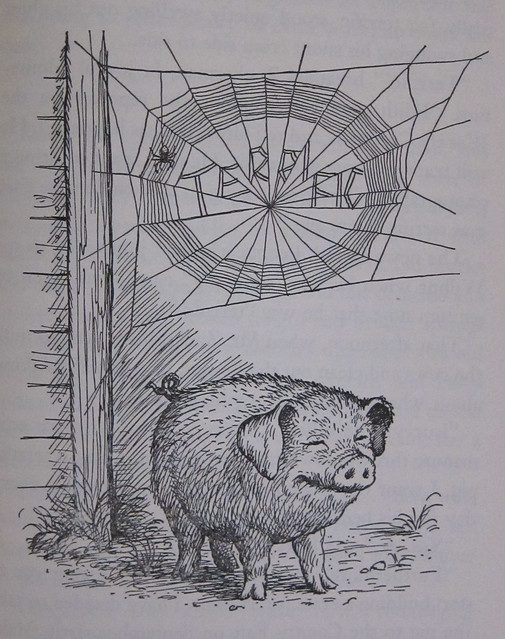

White was fascinated by spiders and thoroughly researched the lives and habits of American arachnids while writing his book. At one point he brought an egg sac from the Maine farm back to the family’s Manhattan apartment. A few weeks later he was delighted to find hundreds of baby spiderlets swarming the top of his bedroom dresser. One suspects that the kindly Dr. Dorian is speaking for the author of Charlotte’s Web when he observes that

I don’t understand how a spider learned to spin a web in the first place. When the words appeared, everyone said they were a miracle. But nobody pointed out that the web itself is a miracle.

Charlotte’s Web was a popular and critical success when it appeared in the fall of 1952. In a review in the New York Times (October 15, 1952) Eudora Welty praised White’s melding of the whimsical and the profound.

What the book is about is friendship on earth, affection and protection, adventure and miracle, life and death, trust and treachery, pleasure and pain, and the passing of time. As a piece of work it is just about perfect, and just about magical in the way it is done. What it all proves — in the words of the minister in the story which he hands down to his congregation after Charlotte writes ”Some Pig” in her web — is ”that human beings must always be on the watch for the coming of wonders.”

Interviewed by George Plimpton and Frank H. Crowther in the Paris Review (Fall 1969), White shared his thoughts on writing for children:

Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time. You have to write up, not down. Children are demanding. They are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth. They accept, almost without question, anything you present them with, as long as it is presented honestly, fearlessly, and clearly. I handed them, against the advice of experts, a mouse-boy, and they accepted it without a quiver. In Charlotte’s Web, I gave them a literate spider, and they took that.

Some writers for children deliberately avoid using words they think a child doesn’t know. This emasculates the prose and, I suspect, bores the reader. Children are game for anything. I throw them hard words, and they backhand them over the net. They love words that give them a hard time, provided they are in a context that absorbs their attention. I’m lucky again: my own vocabulary is small, compared to most writers, and I tend to use the short words. So it’s no problem for me to write for children. We have a lot in common.

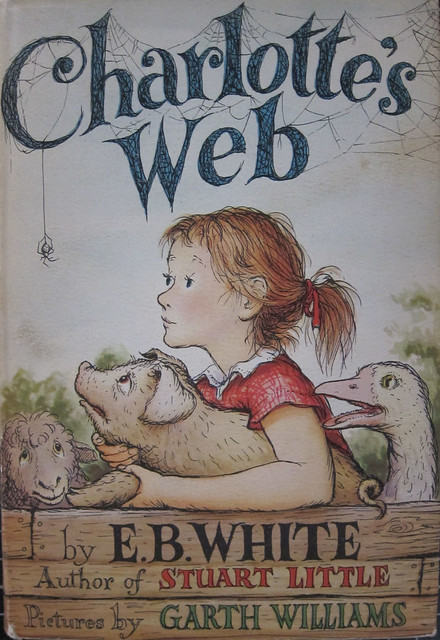

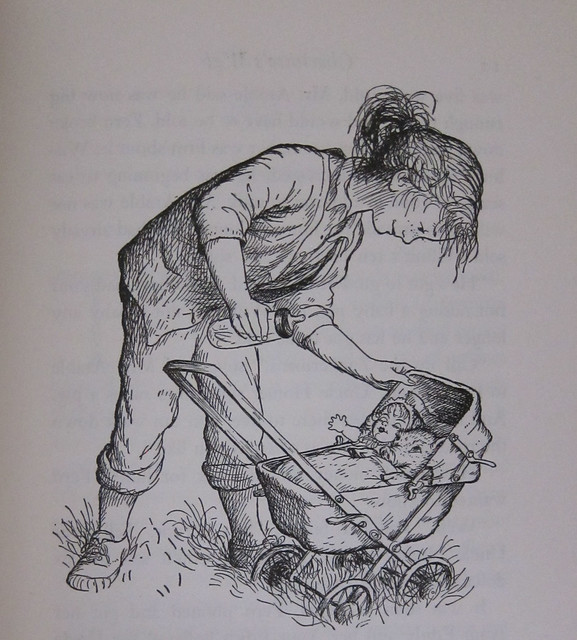

The first edition of Charlotte’s Web featured 46 illustrations by Garth Williams. Williams had also illustrated White’s first children’s book Stuart Little. An aspiring but unsuccessful New Yorker cartoonist at the time, Williams had been offered the Stuart Little assignment by Ursula Nordstrom after several other illustrators turned it down. But Williams’s precise line drawings proved a good match for E. B. White’s prose, and he was Nordstrom’s immediate choice for Charlotte’s Web. Williams went on to illustrate nearly 100 children’s books, including titles by Margaret Wise Brown, Charlotte Zolotow, George Selden, and the 1960s reissue of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s complete Little House series.

Williams is said to have used his oldest daughter, Fiona, as the model for Fern Arable.

ZSR Library’s first edition of Charlotte’s Web is one of many E. B. White titles from the Lynwood Giacomini collection of 20th century American literature. The Giacomini collection was purchased by the library in 1976.

8 Comments on ‘Charlotte’s Web, by E. B. White (1952)’

Thanks for picking this book of the month, Megan. It is one of my all time favorites, and I’ve read it to each of my children and they now love it too.

What a bright spot in the day! Thanks for sharing the back story of Charlotte’s Web and EB White. It’s one of my favorites, too.

As the web says: “Terrific”

Lovely post, Megan.

I look forward to being able to share this, and many other children’s treasures, with my own son one day! And EB White’s assessment of children in his “Paris Review” interview recounted above is spot-on: “They are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth. They accept, almost without question, anything you present them with, as long as it is presented honestly, fearlessly, and clearly.”

This post was a wonderful way to wrap up my day today! Stuart Little was a favorite of mine too. Do we have it as well?

Yes, we have Stuart Little and Trumpet of the Swan, as well as many of E.B. White’s adult titles.

A great post, Megan! It makes me want to read them again. I haven’t read Trumpet of the Swan but will make it a point to do so.