This article is more than 5 years old.

This week I attended the third annual “Understanding the Medieval Book” symposium at the University of South Carolina. It was my first time attending this seminar, which is organized by Dr. Scott Gwara of the USC English department and held in USC Library’s Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. This year’s seminar was led by Dr. Eric Johnson, Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at Ohio State University. Participants included teaching faculty, librarians, and students from various academic institutions. During the two-day symposium Eric described in detail the physical and textual features of medieval manuscripts, with a focus on religious texts. We learned about how manuscript books were created– from the making of parchment, to the scriptorium, to the bindery– and how they were used by their original owners. We also talked a lot about ways to use medieval books and fragments in the college (and even K-12) classroom.

ZSR’s Rare Books Collection does not have an extensive collection of medieval manuscripts. We have five manuscript codices (bound volumes) which I believe date from the late 14th/early 15th centuries. All are religious works in Latin. We also have a few manuscript fragments taken from larger works.

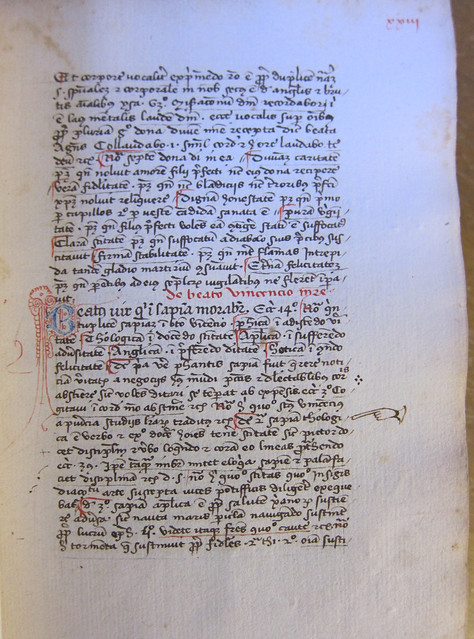

The image above is a page from one of ZSR’s manuscript codices. It is probably Italian (though the text is of course in Latin) and has many typical features of a manuscript from the 14th century. The red and blue ornamentation is not just decorative. Rubrication in medieval manuscripts served as a sort of punctuation, orienting the reader to line breaks and different sections in the text. Marginal notes and symbols, like the manicule (pointing finger), could be used to highlight important passages, add text or commentary, or correct errors in the text.

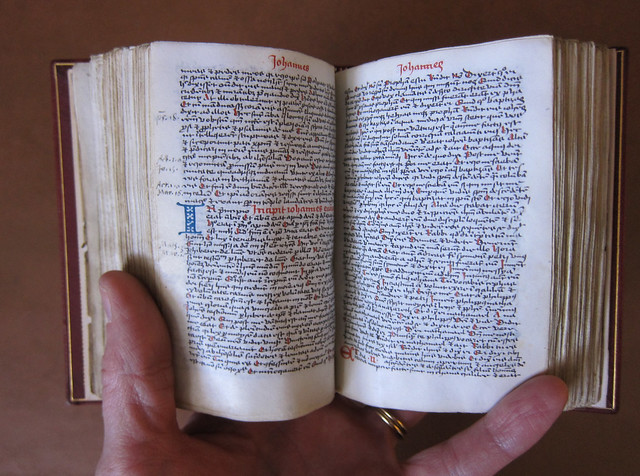

This very small New Testament manuscript from our collection is an example of the trend for “pocket Bibles” which began in the 12th century.

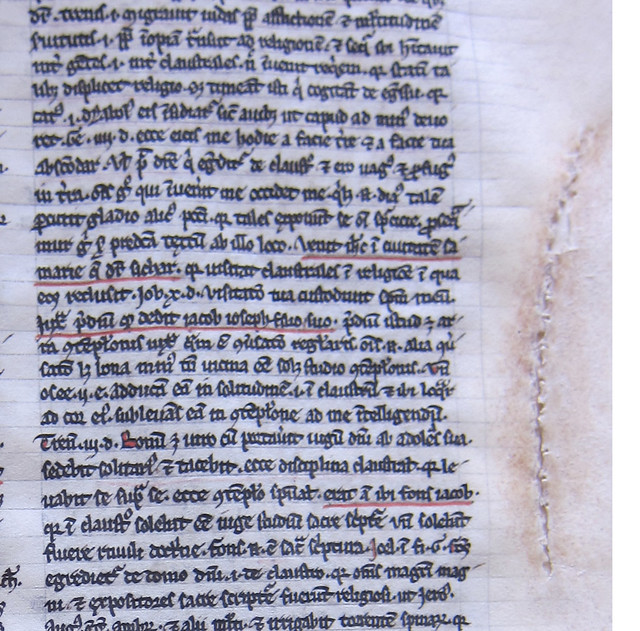

Most medieval manuscripts were written on parchment (also called vellum), which was specially prepared animal skin, usually goat, sheep or calf. Parchment was durable but very expensive, so bookmakers on a budget often made do with lower-quality skins. These might have uneven pigmentation, holes, or other flaws. The image above is a detail from another of ZSR’s manuscript books. The right margin shows a tear in the parchment, which was at one point repaired by sewing up the hole with thread.

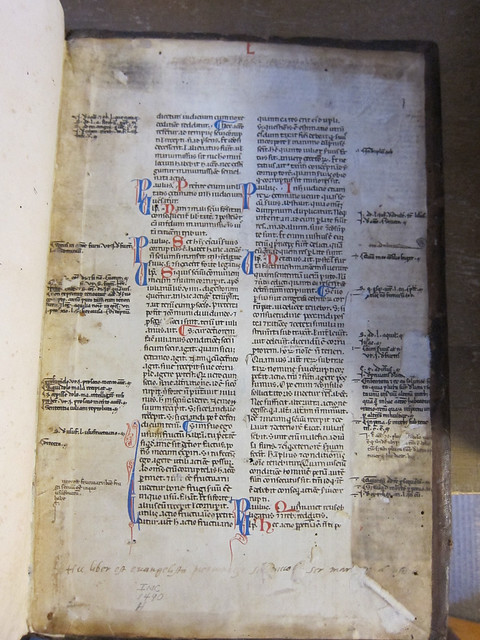

Manuscript production in Europe fell off rapidly with the invention of printing from moveable type in the mid-1400s. Manuscript books were sometimes disbound and the parchment sheets put to other uses. One typical use was in the bindings of other books. Above is a manuscript page pasted inside the cover of a volume of the works of Horace, printed in Venice in 1490. Below, a page from a manuscript missal covers the outer binding of a 1532 Basel imprint.

Though the ZSR medieval manuscripts collection is not large, it gets a lot of use. I show the books to many medieval and Renaissance history and literature classes, and my History of the Book class uses the manuscripts extensively. And of course I pull them out every time someone asks the ever-popular “What’s your oldest book?” question. My goal in attending the USC symposium was to learn more about medieval manuscripts so that I could use them more effectively in teaching and so that I could create catalog records for our codices, which are currently undocumented. I definitely learned a lot, and I met some terrific medievalists. In fact, Dr. Gwara from USC and Dr. Jo Koster from Winthrop University have volunteered to make a site visit to ZSR next week, to look at our manuscripts and help me identify and describe them in detail. So check back for part 2 of this post, in which we’ll learn everything we ever wanted to know about medieval manuscripts at ZSR!

4 Comments on ‘Medieval Manuscripts at ZSR, Part 1’

This sounds like a wonderful symposium, and I look forward to hearing what Dr. Gwara and Dr. Koster have to say about our medieval volumes!

I can’t believe I’m going to miss the medievalists visit! I will now think about parchment paper for baking very differently:) Thanks for the report and I can’t wait to hear more.

I liked the description of the the re-use of manuscripts when movable type came along.

I see this often in preservation work and I believe the practice of using ‘discarded paper’ continued well into the 20th century.

Fascinating Megan!

Looking forward to the report in Part Two!