This article is more than 5 years old.

The following is a joint post by Megan Mulder (Special Collections Librarian) and Chelcie Rowell (Digital Initiatives Librarian).

History of Alexander’s Feast

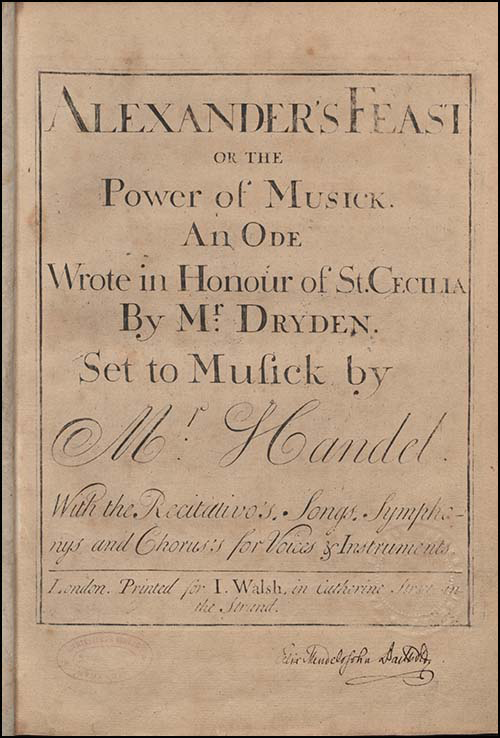

The 18th century edition of Handel’s Alexander’s Feast has one of the most interesting provenances of any book in Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s Special Collections department.

The work is based on an ode in commemoration of St. Cecilia’s day by English poet John Dryden (1631-1700). Dryden’s “Alexander’s Feast” tells a story from the life of Alexander the Great, in which the conqueror and his soldiers enjoy a drunken feast in celebration of their victory over the king of Persia. The bard Timotheus provides entertainment, and his poetic and musical skill inspire Alexander and his men to a frenzy of revenge against the conquered city of Persepolis. Dryden’s poem is more cautionary than celebratory, as the “power of music” is used for morally questionable ends.

Nonetheless, Dryden’s poem was a great critical success when it was first published in 1697, and it was apparently still popular enough nearly 40 years later for George Frideric Handel (1685- 1759) to choose it as the inspiration for a new musical work. Handel’s Alexander’s Feast was well received at its 1736 London premiere and was performed many more times during the 18th century. Published versions of Handel’s score began to appear shortly after its first performance.

Wake Forest’s copy of Alexander’s Feast was likely published around 1750. Its first recorded owner was William Hawes (1785–1846) an English musician who eventually became master of choristers at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

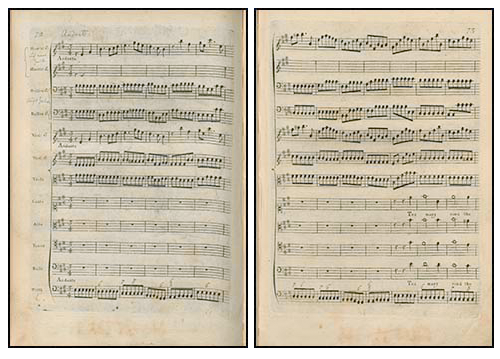

At some point the book made its way to a Stuttgart bookseller and was purchased by the famous German composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847). Mendelssohn signed the front endpaper and the title page, and he also annotated many pages of the score. The notes may well have been for a performance at the Aachen music festival in 1846, which featured an appearance by the famous singer Jenny Lind.

After Mendelssohn’s death in 1847, the book’s provenance again becomes murky. But it was, at any rate, purchased from a rare books dealer in 1958 for the Wake Forest University library. For the past 50 years the volume has been part of the Rare Books Collection at Z. Smith Reynolds Library. It is an interesting object for students of music history. But in the absence of a large collection of related materials at Wake Forest, it has not been well known to Mendelssohn scholars. So Special Collections librarians were pleased to learn of an opportunity to contribute to a project at the Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften in Leipzig. This project, which began in 1959, is working to publish the complete works of Mendelssohn.

Digitization of Alexander’s Feast

In order for ZSR’s Alexander’s Feast to be included in the Leipzig Mendelssohn project, we needed to digitize the entire book. We wanted to do this in such a way that users of the digital surrogate would experience the materiality of the book—the physical organization and details—in addition to being able to read the text.

Capturing digital images of each page of Alexander’s Feast presented a familiar challenge for the Digitization Lab at ZSR. We wanted to make sure that we created a faithful digital representation of the physical object. To this end, we cropped the images of the front cover and back cover such that all four edges are visible. Additionally, we cropped the images of interior pages such that the gutter is visible on the right side for images of verso (left) pages, while the gutter is visible on the left side for images of recto (right) pages. Our goal is to provide viewers as much context about the physical object as possible within the constraints of the hardware and software that we use for digitization.

A best practice for the digitization of special collections materials is to create both a preservation copy and an access copy. In the case of Alexander’s Feast, we created a high-resolution TIFF file of each page of the volume, including the front cover, the marbled endpapers, and the back cover. The advantage of preservation copies is that they’re flexible; they allow different kinds of access copies to be generated as the needs of viewers, as well as the constraints of the systems that present these materials to viewers, both evolve.

The access copy of Alexander’s Feast, available in our Digital Collections, is a single PDF that incorporates all of the pages of the bound musical score.

Future Uses of Alexander’s Feast

Wake Forest’s copy of Alexander’s Feast has been cataloged and available to researchers for decades, and Special Collections has provided digital files and photocopies of relevant pages to remote researchers on request. But its inclusion in the Mendelssohn project will situate the material within the context of Mendelssohn’s career and may bring the item to the attention of international researchers. If this occurs, we will be able to provide remote researchers with high-quality digital images of the book’s pages.

In addition to broadening accessibility, digitizing special collections may enable new paths of inquiry, especially in the digital humanities community. Digitizing sheet music presents tantalizing opportunities. For instance, imagine an interface that displays a moving bar indicating the place in time on the sheet music alongside an audio or video recording of a performance.

Do you have an idea for a digital humanities project that could build upon digitized music scores? Contact us!

6 Comments on ‘Alexander’s feast; or, The power of musick (1750)’

What a great collaborative project and story. Thanks so much.

Beautiful work and interesting project. Thanks for sharing it,

What a treasure in ZSR Library’s collection. Thanks for sharing!

Simply amazing! I talked with a student who worked on this project and he told me he had the best [student] job in the Library. After seeing this, I completely understand why he would say that!

Woo Hoo! Takes me back to my days as a musicology student! 🙂

Had no idea we had this fascinating artifact documenting Mendelssohn’s campaign to revive the Baroque masterpieces for 19th-century audiences. Thanks so much for doing this!