This article is more than 5 years old.

Modern cooks have it easy. If our Thanksgiving preparations go awry, we have shelves of books to consult for advice, not to mention Google, or, as a last resort, the Butterball hotline. Preparers of the original 17th century feast would have had to rely on oral traditions and perhaps a few handwritten “receipts,” which tended to be minimally instructive.

In the late 18th century, authors and publishers recognized a need (not to mention a market niche) for books that provided not just lists of ingredients, but instructions on how to acquire, store, cook, preserve, and serve food. Most were targeted at young, middle-class women setting up housekeeping for the first time. These books proved extremely popular, and a new genre was born—the cookbook.

Authors like Hannah Glasse, Maria Rundell, and Amelia Simmons dispensed helpful advice along with varying degrees of moral instruction to the young housewives of late 18th and early 19th century England and America.

Many cookbooks published in the United States in the early 19th century were reprints of English titles. By the 1830s America was asserting its cultural independence from Europe, and cookery books were no exception. Cookbook author and hotel chef J.M. Sanderson wrote that

The American stomach has too long suffered from the vile concoctions inflicted on it by untutored cooks, guided by senseless and impracticable cook-books; and it is to be hoped, that as this subject is now becoming more important in these days of dyspepsia, indigestion, &c., a really good book will be well patronized, and not only read, but strictly followed; and let it not be said hereafter that “the American kitchen is the worst in the world.”

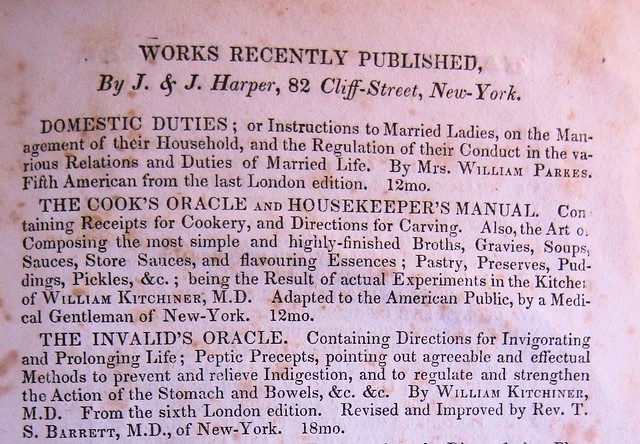

The New York publishing firm Harper & Brothers offered many affordable books on cookery and housekeeping.

In 1831 they came out with a new title, Modern American Cookery, by one Prudence Smith.

Research yields no biographical information on Prudence Smith, and a perusal of the lengthy “Author’s Preface” to Modern American Cookery suggests why. Described in a note from the publishers as a “very singular and learned” treatise on “the great importance of Cooks and Cookery,” the preface is a tongue-in-cheek parody of earnest introductions found in previous cookbooks.

“Prudence” is purportedly a middle-aged spinster who has devoted her life to the intensive study of food and cookery. Citing both classical sources and modern philosophers, she argues that cooking is superior to all the other arts and sciences:

Why doth the poet steal verses, the historian invent history, the romance-writer compile romances, the critic retail all other opinions save his own, and the philosopher stultify himself and his readers with abstract speculation? Of a certainty for no other end than that they may be enabled to partake in the marvelous productions of the genius of [cookbook author] Mrs. Glass, videlicet, that they may eat. . . . Without eating there would be no philosophy, no poetry, no fine arts, no creations of fancy, or productions of the intellect.

In her 30 years of research, Prudence has compiled thousands of recipes and has “tried every one and tasted the result.”

If it was marvelously excellent, and of a triumphant relish, I did forthwith record it in my receipt-book. . . with certain notes of admiration, the number of which indicated the degree of its perfection.

Eventually Prudence accumulates enough recipes to fill 20 volumes. Although her brother discourages her from publishing them (“saying, that after all there was nothing original in them except a new recipe for making apple-sauce”), Prudence journeys to New York with her manuscript in hand. A publisher is found, but he is unwilling to commit to more than one volume, and Prudence must select only “those receipts which had six notes of admiration to them by which means the cream of my twenty volumes was skimmed, as it were, into one milkpan.”

Nevertheless, Prudence remains confident that her small volume of six-star recipes can be life-changing, especially for young girls, to whom she addresses herself in the preface’s closing paragraph:

Let [them] abandon mischievous novels, unseemly romances, and naughty poetry, and cultivate as well as enrich their minds by a constant perusal and practice of the precepts contained in this new, darling little book. . . . So may they in good time wed some rich husband who can afford to practice all my precepts, live in a three-story house with mahogany doors, red window-frames, and marble mantelpieces, keep a French cook, and liquidate his debts at least once in his life by advertising his creditors that he has stopped payment.

Sadly, the nameless Harper & Brothers employee responsible for creating Prudence Smith did not add any editorial commentary on the actual recipes in the collection. They are a standard compilation of early 19th century cooking, probably largely borrowed from other cookbooks. (Though as Prudence herself observed, “if people now-a-days published nothing but what was original the press would stand as still as old Squire Doolittle’s mill… built on Little Dry River.”)

Modern American Cookery was nonetheless popular enough to merit a second edition published in 1835, of which ZSR Special Collections holds a copy. It was well used by its original owner, Hannah Jane King, for penmanship practice as well as (presumably) cooking.

Although Hannah Jane likely would not have celebrated Thanksgiving in the 1830s and 40s, Modern American Cookery provided her with plenty of instruction on how to roast a turkey, covered in both the “Roasting” chapter and another titled “To Dress Poultry.” The latter advises that

The best way to roast a turkey is, to loosen the skin on the breast, and fill it with forcemeat made thus:– Take a quarter of a pound of beef-suet, as much crumb of bread, a little lemon-peel, an anchovy, some nutmeg, pepper, parsley, and thyme; chop and beat them all well together, mix them with the yelk [sic.] of an egg, and stuff up the breast. When you have no suet, butter will do.

There were also instructions, with diagrams, on how to carve turkey and other meats.

An entire chapter devoted to “Gravies and Sauces” offered many options for condiments. For a “Rich Sauce for Fish or Turkey” one should

Roll three-quarters of a pound of butter with a tablespoonful of flour, to which add a small quantity of water, and melt it; to this you must add half a pint of thick cream, one anchovy finely minced, but not washed; place the whole over the fire, and, as it boils, add two or three tablespoonfuls of soy. Pour it into the sauceboat, with the addition of salt and lemon. In making this sauce, great care is requisite to keep it stirring, as it will otherwise curdle.

Vegetables got short shrift in Modern American Cookery, with just one very brief chapter on their preparation. Hannah Jane would have been left to her own devices for making mashed potatoes. But there was a promising, if labor intensive, recipe for green beans:

First string them, then cut them in two, and again across; but if you would do them nice, cut the bean in four, and then across, which is eight pieces. Lay them in water and salt; and when your pan boils, put in some salt and the beans. When they are tender, they are done enough. Take care they do not lose their fine green. Lay them in a plate, and have butter in a cup.

Pies, on the other hand, were covered extensively. For pumpkin pie

Take out the seeds and pare the pumpkin; stew and strain it through a colander. Take two quarts of scalded milk and eight eggs, and stir your pumpkin into it; sweeten it with sugar or molasses to your taste. Salt this batter, and season with ginger, cinnamon, or grated lemon-peel to your mind. Bake with a bottom crust.

Modern American Cookery also assumed that cranberries would be served in pie form:

The cranberries must be stewed with the sugar; the seasoning is nutmeg or cinnamon. Bake them in deep plates, with one crust.

With the lack of coffee shops in antebellum America, Hannah Jane would have had to be her own barista. Fortunately there were instructions for making a latte- a.k.a. “Coffee Milk”:

Boil two ounces of well-ground coffee in a quart of milk for twenty minutes, and put in a shaving or two of isinglass to clear it; let it boil a few minutes, stand it by till fine, then sweeten to taste.

A chapter called “Useful Recipes” offered solutions for the spills and accidents that often occur at holiday dinners. Various potions were recommended for cleaning spots from linen and upholstery, and for mending broken dishes. This one was intended “To Mend Broken Glass”:

Take two quarts of litharge, one of quicklime, and one of flint glass, each separately and very finely powdered, and work the whole up into a paste with drying oil. This is an excellent cement for china or glass, and only becomes the harder by being immersed in water.

And finally, if Hannah Jane’s guests overindulged at the table, a chapter on “Family Medical Recipes” offered one for “Stomachic Pills”:

Take extract of gentian one drachm, powdered rhubarb and vitriolated kali each half a drachm, oil of mint sixteen drops, and of the common sirup enough to make the whole into pills. Three of these pills taken twice a day will strengthen the stomach and keep the body gently open.

Modern American Cookery, and countless other books like it, offered guidance on how to keep a family healthy and fed—and suggested that this endeavor required some skill, intelligence, and even artistry. On the eve of a major cooking holiday, one likes to think that “Prudence Smith” was not entirely tongue-in-cheek in her meditations on the importance of food:

In vain may philosophers confound themselves and their readers with definitions of reason and instinct, which run into each other like butter and sugar in a hot apple-pie. I say in vain; for were it not for the art of cookery, it would for ever remain impossible to give a just definition of man. He is emphatically a cooking animal, or he is nothing.

2 Comments on ‘Modern American Cookery, by Prudence Smith (1835)’

I love the picture of the “well ordered mid 19th century kitchen” complete with mouser! This is a lovely, timely look at the “art of cookery.” Thanks!

A perfect read for this Thanksgiving morning!