This article is more than 5 years old.

Banned Books Week is observed each September by librarians, publishers, authors, educators, and readers to show “support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.” By calling attention to various attempts to restrict access to books and other materials, Banned Books Week reminds readers that freedom of access to ideas and information is not something to be taken for granted.

Banned Books Week was begun in 1982, but book banning has a much longer history. ZSR Special Collections holds a copy of one of the most famous banned books of all time, Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) became interested in physics and astronomy while a student at the University of Pisa. By 1592 he was a professor of mathematics at the University of Padua and was conducting extensive scientific experiments. He was naturally interested in one of the great controversies of his day, which concerned the theories of Polish mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543).

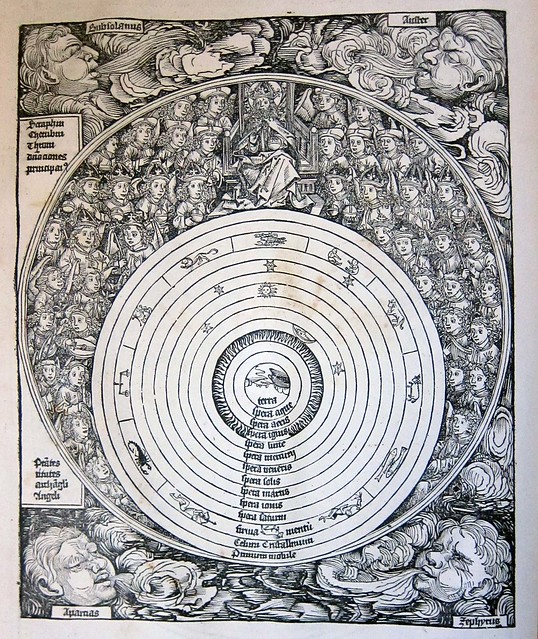

Copernicus had been one of the first European scholars to question the traditional Ptolemaic universe—the idea that the earth remained immobile at the center of the universe while the sun, planets, and stars revolved around it in concentric spheres. This model was posited by the Greek astronomer Ptolemy (ca. 150 CE), based on the philosophy of Aristotle (384-322 BCE).

Aristotle’s concept of an imperfect and changeable earthly realm surrounded by an eternal and immutable heaven had become integral to medieval Christian theology. Thus many religious authorities – in particular the Catholic Church—found Copernicus’s challenge to this model an unwelcome threat.

Galileo’s work in astronomy and physics lent support to the Copernican theory. Working with Dutch prototypes, Galileo developed a telescope that allowed him to make unprecedented observations of the moon, sun, and other planets in the solar system.

His work made him famous and gained him the patronage of the powerful Medici family. But it also attracted the attention of church authorities, who were less impressed.

In 1616 Galileo was called before a committee of the Roman Inquisition and instructed to stop teaching and writing anything that supported Copernicus’s heliocentric model. Galileo’s books were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum—the Catholic Church’s list of banned books.

Galileo kept a low profile for the next decade, but in 1623 his friend Maffeo Barberini was elected Pope. He requested and received permission from the new Pope Urban VIII to publish a book on the Copernican controversy. The result was Diologo … Sopra I Due Massimi Sistemi del Mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems), published in Florence in 1632. Pope Urban had specified that Galileo should present the argument as a purely mathematical hypothesis and that he should give equal weight to both the Ptolemaic and the Copernican theories.

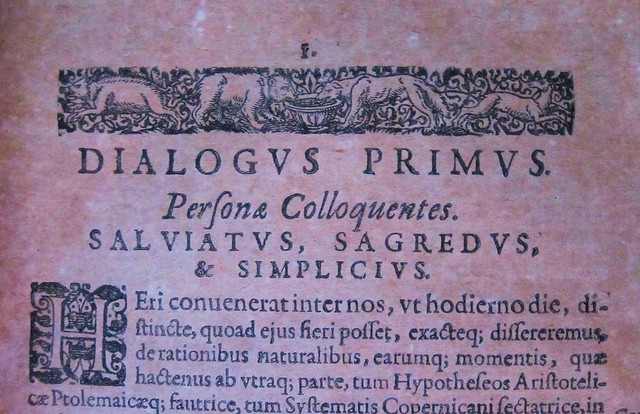

Galileo framed his argument in a dialogue (or more accurately, a triologue) among three fictional characters: Salviati, a proponent of the Copernican theory; Sagredo, his friend, who has no fixed opinion but is eager to learn; and Simplicio, a traditionalist who defends the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian view.

It seems that Galileo genuinely believed he was presenting an unbiased account of the argument. But it was immediately clear to his readers where his sympathies lay: in the fictional debate, Salviati easily bests the unfortunately named Simplicio, who comes across as fairly dimwitted. Pope Urban was not pleased when he realized that the objective and dispassionate treatise he had approved was actually a thinly veiled manifesto for Copernicanism. Worse, Urban believed that Simplicio was in fact a satiric portrait of himself. Galileo had lost a vital ally, and within a year of the Dialogue’s publication he was called before the Inquisition, convicted of heresy, and placed under house arrest.

Galileo was by then nearly 70 years old and in poor health. His scientific career was over, but his influence on the scientific revolution in Europe had just begun.

Even as the Dialogue was being banned in Rome, Galileo’s friend Elia Diodati was making plans for an international edition. Diodati recruited Matthias Bernegger, a university professor in Strasbourg, to translate Galileo’s text into Latin, the universal language of European scholarship.

Diodati also found a publisher for the book, the Dutch Elzevier firm, one of the most prestigious scholarly publishers in 17th century Europe, based in safely Protestant Leiden. Anticipating an eager audience, the Elzeviers hurried the book into print. Printing (by David Hautt of Strasbourg) was begun while the translation was still ongoing. And the book was published in a large edition of about 600 copies.

Copies were available for sale by March of 1635. The book bore the new title Systema Cosmicum, but the text was nearly identical to the 1632 Dialogue. One striking difference, however, was the newly engraved frontispiece for the Elzevier edition. As in the Italian edition, the engraving showed Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Copernicus engaged in conversation. In the Italian illustration, all three were elderly and all were equally absorbed in the debate.

In the new edition the Greek philosophers were still elderly—Aristotle appeared to be leaning on a cane—but Copernicus was much younger. While Aristotle and Ptolemy focused on the model of the old universe, Copernicus, holding his new model, looked out at the reader, as though appealing directly to the sophisticated, intelligent European of 1635.

The banner overhead pays tribute to Galileo’s patron, Ferdinando II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Since the pages would have been sold unbound, in typical 17th century publishing practice, the illustration would have served as a sort of cover advertisement for the contents inside.

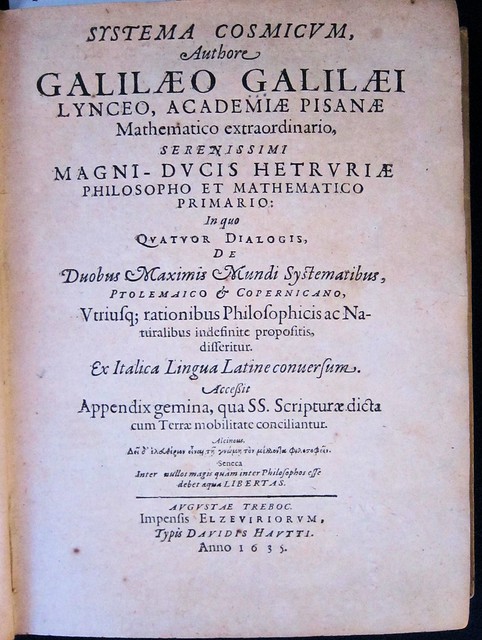

For the editors and publishers of the Systema Cosmicum, the idea of intellectual freedom was as important as the specific arguments about the nature of the universe. The title page of the Elzevier edition prominently featured Galileo’s credentials, and it announced that the two world systems would be evaluated in “philosophical and natural” arguments. It also advertised an appendix in which it would be demonstrated that the Copernican system was compatible with Christian scriptures.

The two quotes near the bottom of the page reinforced the theme of intellectual freedom and free inquiry. The first, from the Greek philosopher Alcinous reads “It is necessary for one intending to be a philosopher to be free in thought.” The second, a quote from Seneca, reads “Especially among philosophers should be equal liberty.”

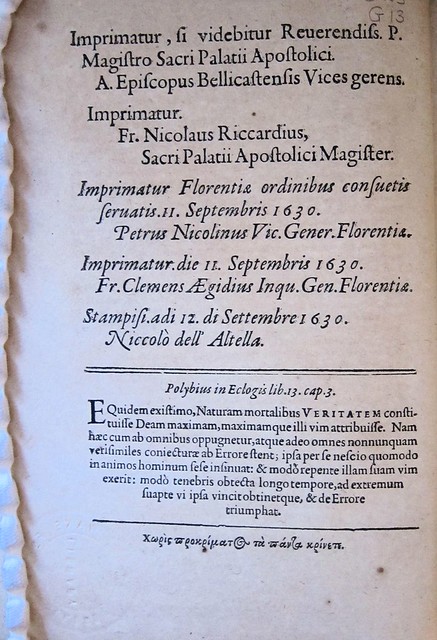

The verso of the title page listed the Catholic authorities who had originally approved publication of the Dialogue and later reneged. And for good measure, there was another quote from a classical author on the theme of truth triumphing over falsehood.

A note by translator Matthias Bernegger addressed to the “Kind Reader” described the reasons for publishing a new edition of the Dialogue. Bernegger claimed that the book had been published without Galileo’s knowledge or consent, a patent falsehood intended to protect the author from more persecution. In fact Galileo knew about and enthusiastically supported the project.

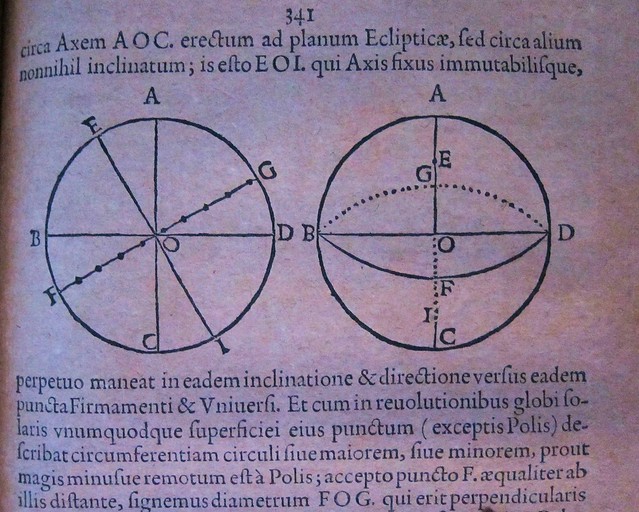

The text of Systema Cosmicum was an example of a new type of discourse taking shape in Renaissance Europe. Instead of basing his discussion of cosmology on theological principles and classical authorities, Galileo evaluated the Ptolemaic and Copernican systems in scientific terms, using mathematical proofs and direct observation to bolster his arguments.

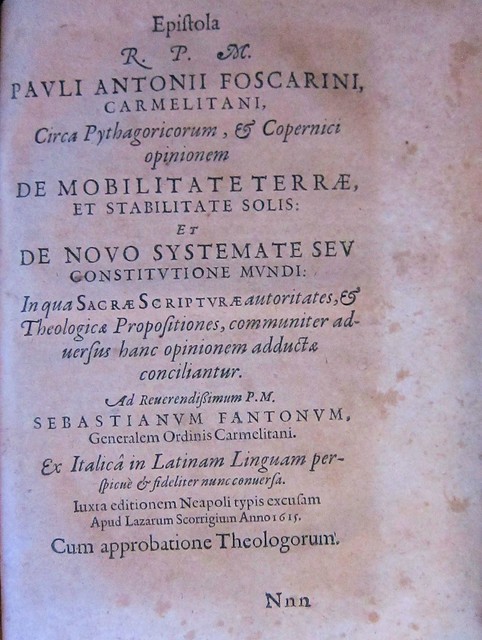

The appendices to Systema Cosmicum were an excerpt from the writings of German astronomer Johannes Kepler and an essay by Carmelite monk Paulo Foscarini, which had also been placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. Both argued that Christian scripture was not incompatible with the Copernican theory, in part because Biblical teachings were not meant to answer questions about physics and astronomy.

The Latin edition of Galileo’s Dialogue was distributed widely throughout Europe. As is generally the case, the controversy surrounding the book only served to pique interest in it. Fierce public debate continued for the next decade, but by the mid-17th century the Copernican model was accepted by most educated Europeans.

Galileo’s works remained on the Catholic Index until the early 18th century. In 1992 Pope John Paul II issued an official apology for the church’s persecution of Galileo.

Galileo would not have called himself a scientist: the term was not coined until the 19th century. But his contribution to modern scientific thought is immeasurable. And Galileo himself has become a symbol of the visionary individual victimized by oppressive authority. Albert Einstein, in a foreword to a 1967 English translation of the Dialogue (University of California Press), wrote that

The leitmotif which I recognize in Galileo’s work is the passionate fight against any kind of dogma based on authority. Only experience and careful reflection are accepted by him as criteria of truth. Nowadays it is hard for us to grasp how sinister and revolutionary such an attitude appeared at Galileo’s time, when merely to doubt the truth of opinions which had no basis but authority was considered a capital crime and punished accordingly. Actually we are by no means so far removed from such a situation even today as many of us would like to flatter ourselves… (xvii)

Not all banned or challenged books end up becoming seminal works in the history of western civilization. But Galileo’s example reminds us that history seldom looks kindly on those who try to suppress “unorthodox or unpopular” ideas through censorship and intimidation.

References

J.L. Heilbron, Galileo (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Maurice A. Finocchiaro, Retrying Galileo (University of California Press, 2005).

Galileo, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, translated by Stillman Drake (University of California Press, 1967).

4 Comments on ‘Dialogus de Systema Cosmicum, by Galileo Galilei (1635)’

Megan,

Awesome story. Thanks for sharing!!!

Can I post your last sentence on my door? That’s a keeper.

Wonderful! Thank you for another fascinating post.

Illuminating stuff, it is always a pleasure to read your essays.

As usual, your posting is captivating!