This article is more than 5 years old.

By the end of the 18th century, Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779) was the most famous furniture designer in England and North America. The term “Chippendale” had come to refer to a style of furniture prevalent throughout Europe and the United States. What started Thomas Chippendale on the road to this renown was the publication of a book.

In 1754 Chippendale was an up-and-coming young furniture designer, recently moved to London. Raised in a family of woodworkers, he presumably received extensive hands-on training in his early life, which no doubt served him well once he began to design his own furniture based on the popular styles of his day. But fashionable London was a competitive market, and Chippendale needed a way to distinguish himself from the crowd.

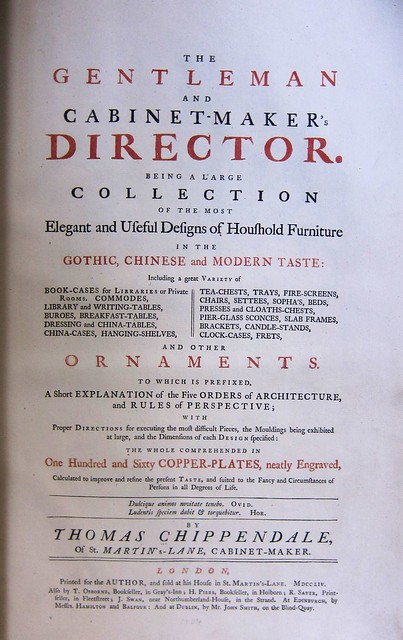

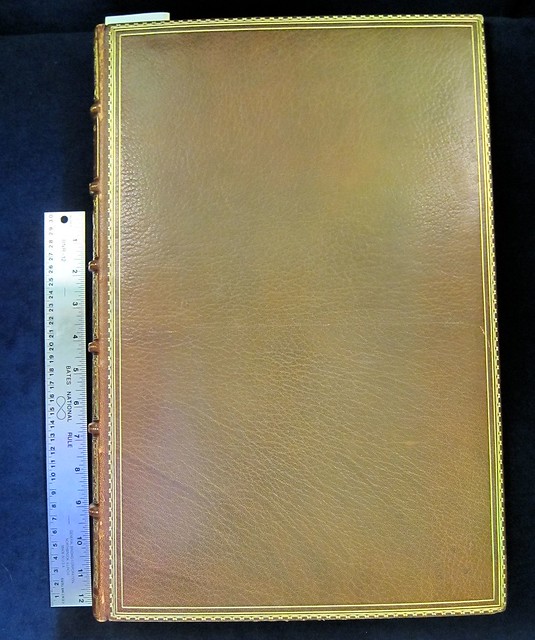

He hit upon the idea of publishing what was essentially a deluxe catalog of his designs. It was titled The Gentleman and Cabinetmakers Director. A few English furniture makers had published their designs before, but nothing had come close to the scale of Chippendale’s large folio volume.

The book was, its subtitle announced, “A Large Collection of the most Elegant and Useful Designs of Houshold [sic.] furniture in the Gothic, Chinese and Modern [i.e., English Rococo] Taste.”

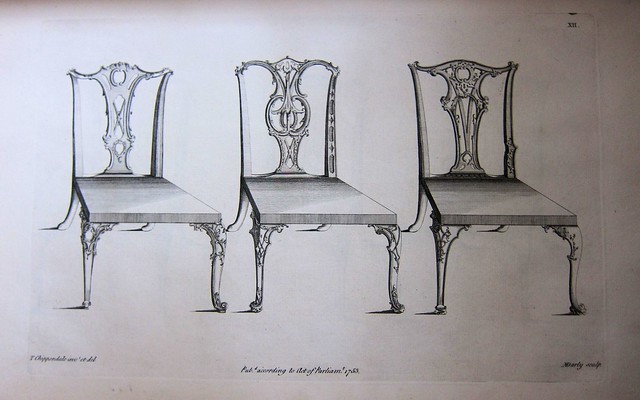

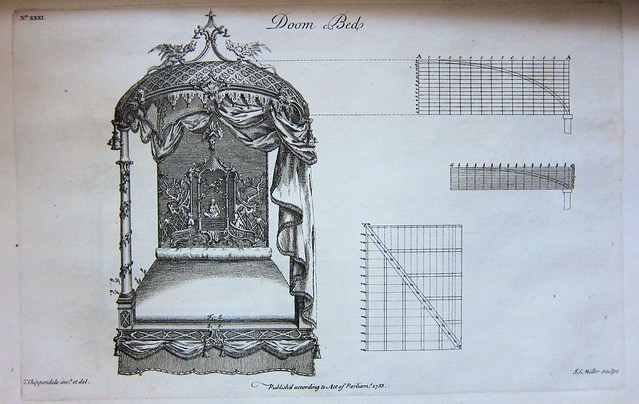

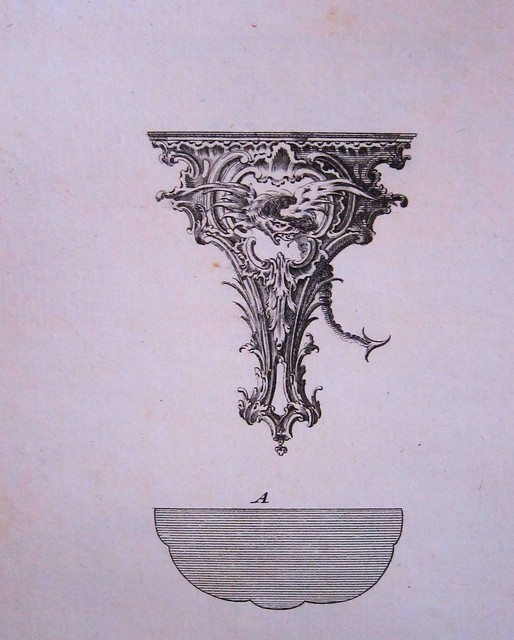

The Rococo style, a French import, was the prevailing fashion in the mid-18th century. It was characterized by elaborate carving and sinuous forms, often featuring decorative elements taken from the natural world—leaves, shells, animals.

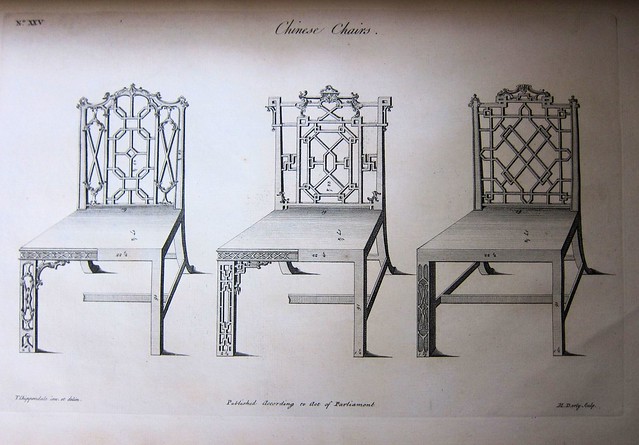

The Gothic style of furniture was part of the medieval revival in art and architecture, which began in the 18th century and became even more prevalent in the Victorian era. Gothic furniture tended to feature elements found in medieval architecture, such as arches and openwork patterns.

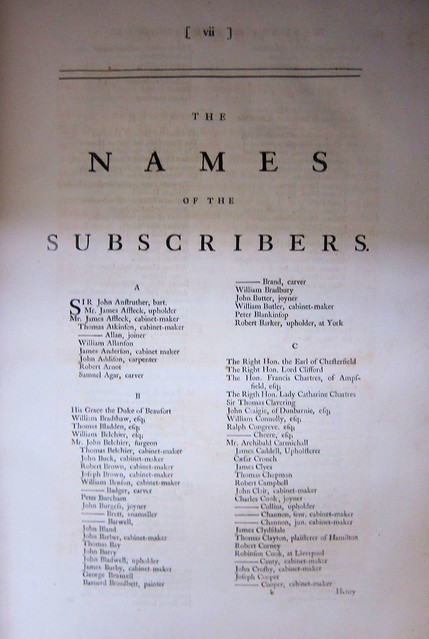

Chippendale self-published the Director, financing his venture by recruiting subscribers—buyers who pre-paid for their copies of the finished book. This was a fairly common practice in the 18th century.

The list of over 300 subscribers in the 1754 first edition of the Director includes both categories of reader mentioned in the book’s title: Gentlemen—members of the aristocracy who would purchase Chippendale’s furniture; and Cabinetmakers—Chippendale’s fellow craftsmen who could adapt his designs for their own use.

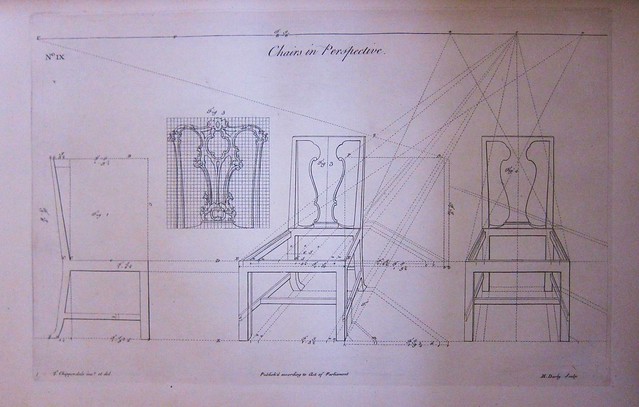

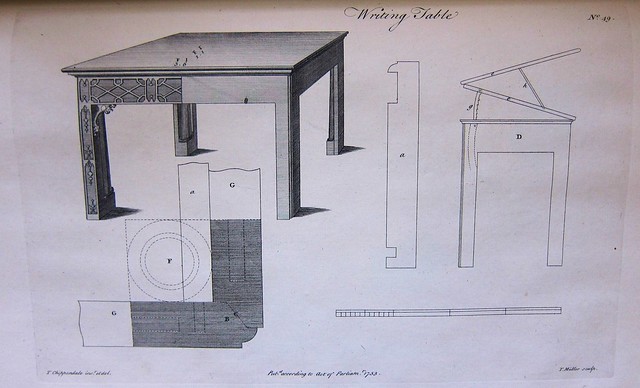

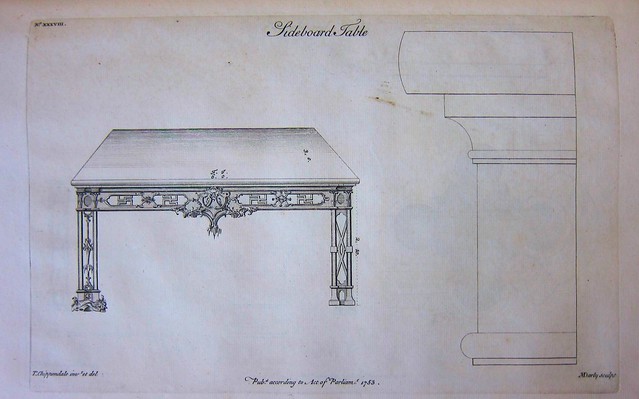

Chippendale’s friend Matthew Darly engraved most of the illustrations, based on Chippendale’s own drawings. The 160 plates show the wide variety of furniture and decorative objects that his workshop could produce. Chippendale also included at the beginning of the book a brief discussion of five orders of architecture and instructions on drawing furniture in perspective.

The more elaborate pieces featured in the Director obviously required a very high level of woodworking skill to execute.

Upon the whole, I have here given no design but what may be executed with advantage by the hands of a skillful workman, tho’ some of the profession have been diligent enough to represent them (especially those after the Gothic and Chinese manner) as so many specious drawings, impossible to be work’d off by any mechanic whatsoever. I will not scruple to attribute this to malice, ignorance and inability: And I am confident I can convince all Noblemen, Gentlemen, or others, who will honour me with their commands, that every design in the book can be improved, both as to beauty and enrichment, in the execution of it…

In fact, many of the designs include instructions for the less experienced cabinetmaker and options for making pieces more or less elaborate, as the craftsman’s skill level and purchaser’s income demanded.

Chippendale’s catalog offered designs for many other household items besides furniture. Candle holders, clock cases, fire screens, shelves, mirror frames, and many other elaborately carved items were available from his workshop.

Chippendale’s Director was not an inexpensive book. It sold for £1.17s in unbound sheets, slightly more for a pre-bound copy. But it apparently sold well enough to warrant a second edition less than a year after its appearance. And in 1762 Chippendale published an updated third edition.

As a marketing tool, the Director was a great success. Chippendale’s business took off, and he was soon overseeing a large workshop of skilled craftsmen. With the publication and wide distribution of his book, Chippendale also –unintentionally—insured his legacy as the 18th century’s best known designer of furniture. Copies of the Director circulated across Europe and North America. Chippendale’s influence was particularly strong in the English colonies, later the United States, as woodworkers adapted his designs to American materials and tastes.

Many copies of the Director made their way to North America, and many examples of Chippendale-inspired furniture from 18th century America have survived. The collection of Winston-Salem’s Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts includes a sideboard based on Chippendale’s design pictured above. By publishing his designs in text and illustrations, Chippendale spread his influence far beyond the reaches of his London workshop.

Interested in learning more about American furniture design? Be sure to visit Reynolda House Museum of American Art’s special exhibit The Art of Seating: Two Hundred Years of American Design.

5 Comments on ‘The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754), by Thomas Chippendale’

Fascinating!

Great post, Megan! I am looking forward to visiting the Reynolda House exhibit, too.

So interesting, Megan! Your timing couldn’t be better, since The Art of Seating includes this quote, writ large above the exhibition: “A chair is a very difficult object. A skyscraper is almost easier. That is why Chippendale is famous.” (Mies van der Rohe). And the sideboard at MESDA is a must-see.

I love it! For those coming to see the Reynolda House exhibition, there is a chair riffing off designs by a later 18th-century cabinetmaker who published a drawing book in four parts, beginning in 1791: Thomas Sheraton.

I loved this post-as usual, excellent reading and I learned something. Thanks!