This article is more than 5 years old.

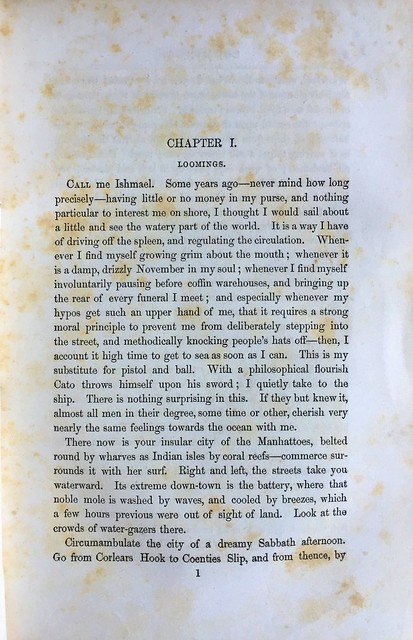

Herman Melville’s Moby Dick has one of the most recognizable opening lines of any American novel. Everyone knows about Ishmael, Captain Ahab, and the Great White Whale. But how many readers have actually made it to the end of Melville’s epic?

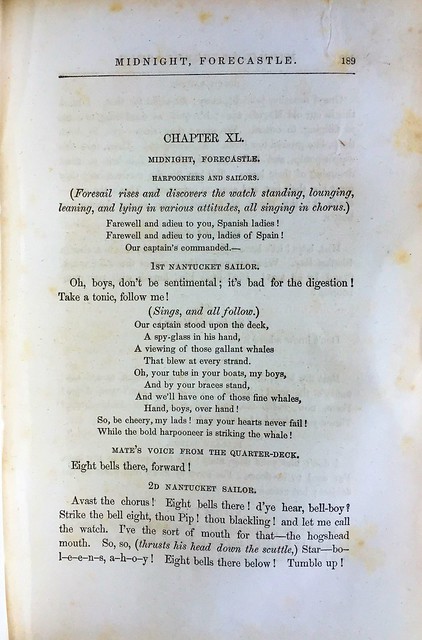

Moby Dick; or, The Whale is today a staple of Best American Novel lists and college syllabi. For the past 160 years, readers have been fascinated and frustrated by Melville’s genre-bending work. A look at the book’s beginnings shows that its story was complicated from the outset.

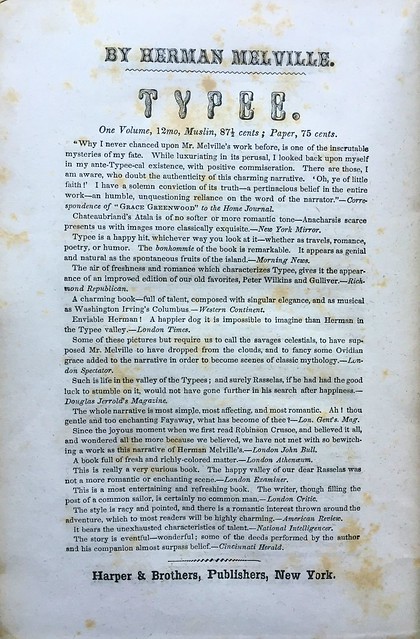

In 1850 Herman Melville was an up-and-coming young author. He had published popular adventure tales like Omoo, Typee, and Redburn, drawn in part from his experiences as a sailor in the South Pacific. But he was ready to write something different. He had recently had a number of formative experiences—a tour of Europe, a passionate encounter with the works of Shakespeare, and a new friendship with one of the most prominent American literary figures of the day, Nathanial Hawthorne. As a result, Melville’s writing was about to take a turn toward the metaphysical.

But Melville also needed his writing to be profitable. His father, a New York merchant, had died bankrupt when Melville was a teenager, and at age 30 he was helping to support his widowed mother and sisters and raising his own young family. Early in 1850 he began writing a book called The Whale, inspired in part by stories of real shipwrecks and giant albino whales.

But after meeting Hawthorne late that summer, he moved his family to rural Massachusetts to be near his new mentor and turned his seafaring tale into a metaphysical tour de force. Melville wrote for 18 months, with his wife and sisters making clean copies of his manuscript pages, and in the fall of 1851 he presented his publishers with a monumental work. It was, in Melville’s own description, “a strange sort of book” (Letters, 108).

Melville hoped that his new book would establish his reputation as a serious literary author. In order for this to happen, Moby Dick would need to be published and reviewed in Britain as well as the United States. American authors of the 19th century were eager to reach a readership in Britain—and vice versa. But the copyright situation in the mid-1800s made this complicated. There was no international copyright agreement between the two English-speaking countries, so pirating of books was rampant. Unscrupulous publishers would sometimes even meet ships at the docks to acquire copies of newly printed books by popular authors. They would then hastily print unauthorized copies and claim American (or British) copyright for the work—with no profit to the author or the original publisher.

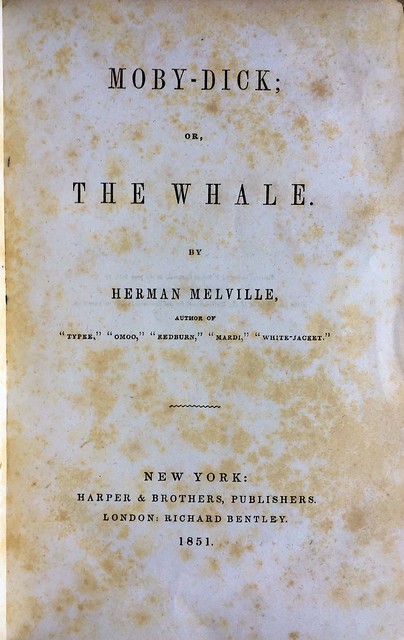

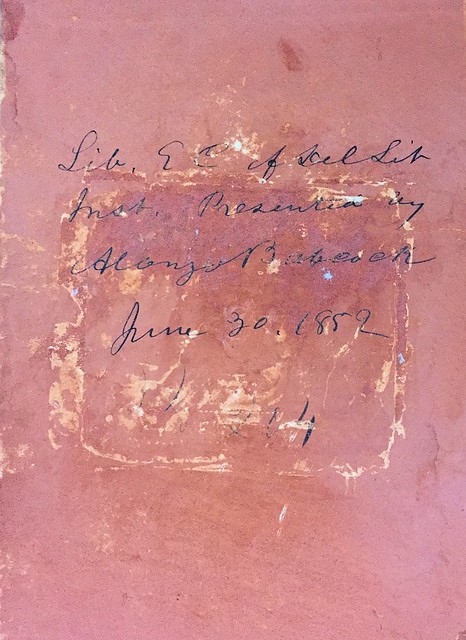

Authors were well aware of this and had strategies to prevent piracy. Melville’s tactic for Moby Dick was one used by many authors: he had the book published first by his London publisher (Robert Bentley) so that he could claim British copyright, but he arranged for the American publication (by Harper & Brothers) to follow quickly on its heels so that book pirates would not have time to print and market unauthorized editions. Bentley’s edition of the book, still titled simply The Whale, was published in October of 1851; Harper’s came out with the renamed Moby Dick just a few weeks later, in November 1851.

Even aside from copyright concerns, there were challenges for an American author dealing with 19th century London publishers. Libel laws were more strictly enforced in Britain, and publishers felt free to alter or expurgate manuscripts without permission from the author– especially when said author was not on hand to see the book through the press.

Melville’s work suffered this fate, even though he had taken measures to avoid it. Instead of turning his handwritten copy over to his publishers, Melville had arranged—possibly at his own expense—to have the book typeset and made into stereotype plates. Stereotyping was a widely used printing technology in the mid-19th century. It involved making a cast of pages set up in moveable type, and then creating metal plates that were used for the actual printing. The great advantage of stereotype plates was that, if a book proved very popular, more copies could be printed quickly, without having to reset the type. But it also made it more difficult to make changes in the text.

Proof sheets were printed from the original plates of Melville’s book, and these proofs were sent to Bentley in London. Since he knew Bentley would set his own type for the English edition, Melville also included manuscript corrections on the printed proofs. Many of these corrections would not make it into the text of the American edition, which would be printed from the already- made plates.

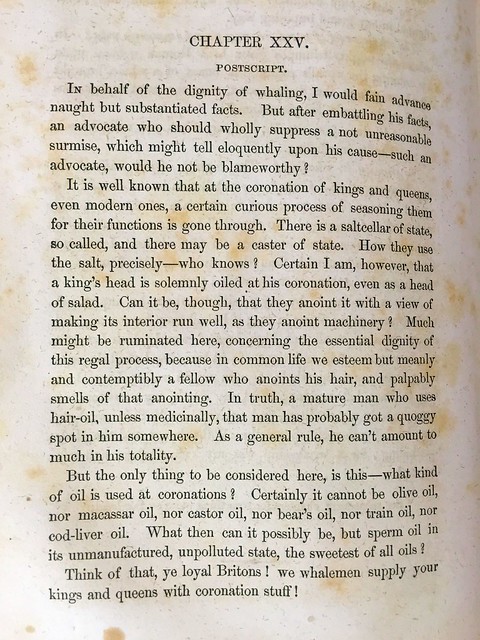

There are about 600 variants between the text of the English and American first editions of Moby Dick. Some are minor differences, but many are not. In addition to incorporating (presumably) Melville’s edits, Bentley expurgated anything vaguely offensive in the text– including all of chapter 25, which speculated on the use of whale oil in English coronation ceremonies.

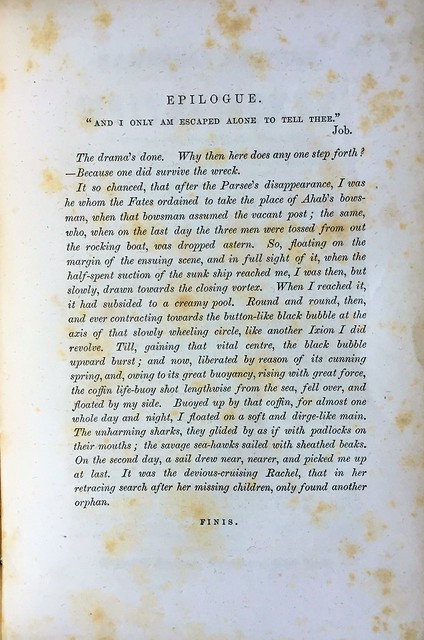

Bentley’s edition transposed Melville’s introductory “Extracts” to the end of the book. And perhaps most egregiously, it did not include the “Epilogue” that explains how Ishmael survived the shipwreck of the Pequod to tell his tale—leaving English readers to puzzle over why the book was narrated by a dead person.

And Bentley was apparently unable or unwilling to accommodate Melville’s request, rather late in the printing process, to change the book’s title to Moby Dick. The English edition retained the more generic title The Whale.

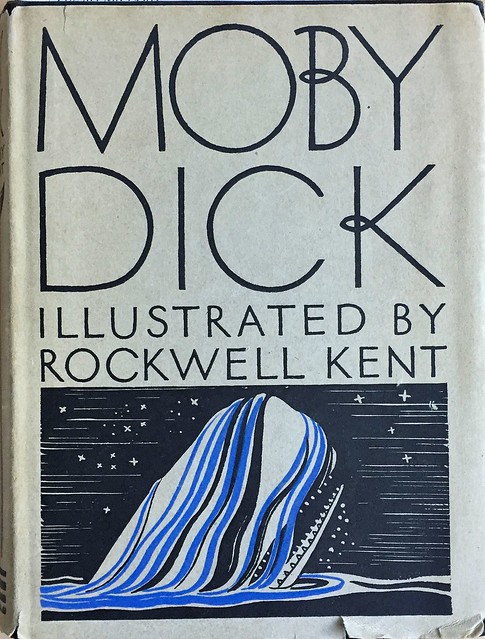

Bentley’s edition was a three volume affair with a decorative binding. Harper and Brother’s American edition was one hefty volume, with most of the copies bound in sea-blue cloth.

Reviews of the book, on both sides of the Atlantic, were decidedly mixed. A reviewer for the English magazine John Bull (October 1851) was enthusiastic:

Of all the extraordinary books from the pen of Herman Melville this is out and out the most extraordinary. Who would have looked for philosophy in whales, or for poetry in blubber? Yet few books which professedly deal in metaphysics, or claim the parentage of the muses, contain as much true philosophy and as much genuine poetry as the tale of the Pequod’s whaling expedition.

But other reviewers and readers agreed with the London Athenaeum (25 October 1851), which groused that “The idea of a connected and collected story has obviously visited and abandoned its writer again and again in the course of composition.”

The Boston Post’s (November 1851) reviewer did not even feel obligated to finish the book before offering his readers a caveat emptor:

We have read nearly one half of this book, and are satisfied that the London Athenaeum is right. . . . It is a crazy sort of affair, stuffed with conceits and oddities of all kinds, put in artificially, deliberately and affectedly, by the side of strong, terse and brilliant passages of incident and description. . . . The production under notice is now issued by the Harpers in a handsome bound volume for one dollar and fifty cents—no mean sum, in these days. . . . “The Whale” is not worth the money asked for it, either as a literary work or as a mass of printed paper. Few people would read it more than once, and yet it is issued at the usual cost of a standard volume. Published at twenty-five cents, it might do to buy, but at any higher price, we think it a poor speculation.

The reviewer for the London Atlas (November 1851) summed up many readers’ frustration with the sprawling and apparently incoherent narrative :

In all Mr. Melville’s previous works, full of original genius as they are, there was to be found lurking a certain besetting sin of extravagance. . . . The book before us offers no exception to the general rule which more or less applies to all Mr. Melville’s fictions. . . . Extravagance is the bane of the book, and the stumbling block of the author. He allows his fancy not only to run riot, but absolutely to run amuck, in which poor defenceless Common Sense is hustled and belaboured in a manner melancholy to contemplate. Mr. Melville is endowed with a fatal facility for the writing of rhapsodies. Once embarked on a flourishing topic, he knows not when or how to stop.

But for Moby Dick’s fans, Melville’s over-the-top style was central to the work’s appeal:

The book is not a romance, nor a treatise on Cetology. It is something of both: a strange, wild work with the tangled overgrowth and luxuriant vegetation of American forests, not the trim orderliness of an English park. Criticism may pick many holes in this work; but no criticism will thwart its fascination. (London Leader, 8 November 1851)

Unfortunately for Melville, the book was not a huge commercial success. And his next book, Pierre; or, The Ambiguities was even less popular. Discouraged, Melville turned to writing magazine articles and short stories; eventually he took a job as a customs inspector in New York. In his later life he took up poetry, but by the time he died in 1891 he was nearly forgotten as a literary figure.

However, the 1920s saw a resurgence of interest in Melville’s works. By the 1930s Moby Dick had been enshrined as a classic of American literature, and its hold on the imaginations of readers has never waned. Melville’s most famous work was reprinted many times during the 20th century, in popular, scholarly, and frequently in lavishly illustrated editions.

Melville himself never denied that Moby Dick was a difficult read. Writing in response to Hawthorne’s praise of the novel, he asserted that “I am not mad. . . But truth is ever incoherent, and when big hearts strike together, the concussion is a little stunning” (November 17, 1851). Moby Dick’s creator would no doubt be delighted that readers are still wrestling with his great metaphysical whale of a book.

4 Comments on ‘Moby Dick, by Herman Melville (1851)’

Awesome post Megan. Thanks!

Fascinating illustration of how, if you think about it, the publishing world really has not changed much, seeing as how we’re all still contending with the metaphysics of copyright strategies, technology problems, printing errors, illustration issues, and cranky reviewers.

Still, ya gotta admire the dude for keeping it weird:

“It is not down on any map; true places never are.”

― Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale

Fascinating differences between the British and American versions. Thanks, Megan!

It’s true—At WFU Press we deal with these same issues between Irish/English editions and our U.S. editions all the time. Great post, thanks!