This article is more than 5 years old.

A dramatist once wrote a play

about an Irish peasant,

We heard some of the audience say

“The motive is not pleasant.”

Our own opinion, we admit,

Is rather—well—uncertain,

Because we couldn’t hear one bit

From rise to fall of curtain.The Abbey Row (Dublin: Maunsel & Co., 1907)

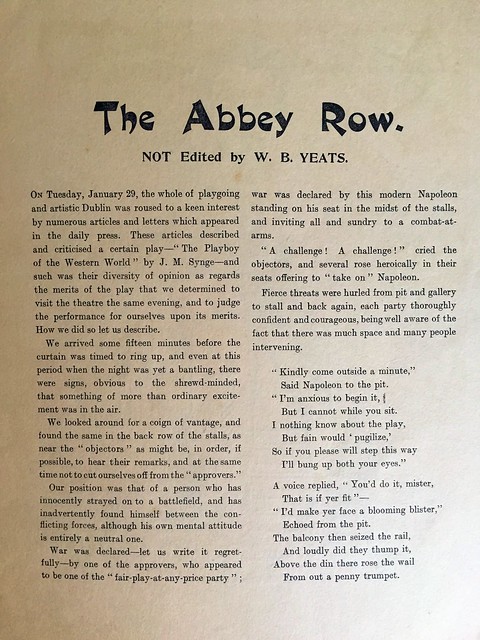

John Millington Synge’s drama The Playboy of the Western World had its premiere at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin on January 26, 1907. But the actors on that first night never made it to the end of the play. Halfway through Act 3, a group of audience members broke out in a near riot, storming the stage and threatening the life of the author.

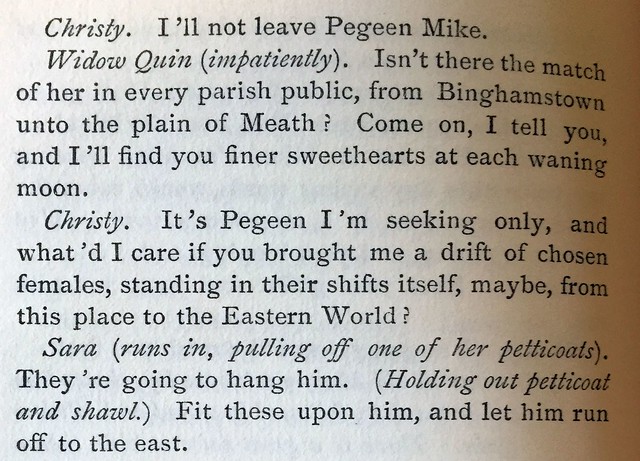

The apparent trigger for the playgoers’ wrath was an indelicate reference to “a drift of chosen females, standing in their shifts [i.e. underwear]”—which prompted Abbey playwright and patron Lady Gregory’s famous telegraph to William Butler Yeats: “Play broke up in disorder at the word ‘shift’”. But in fact Synge’s conjuring of nearly-naked maidens was just the last straw. The real problem was that the play took deadly satirical aim at many things that Irish nationalists held most dear—Catholicism, Gaelic hero tales, and the general nobility of the Irish peasant class.

The play fared no better over the next several days of its week-long run. Organized protesters showed up at the theater to disrupt the proceedings each night, sometimes clashing with supporters of Synge and the Abbey. Yeats, who was the Abbey’s artistic director, cut short a lecture tour and hurried back to Dublin in an attempt to restore order—to no avail. At one point he called in police to arrest the rioters. This further enraged the nationalist protesters, who accused the Abbey– which purported to be Ireland’s national theater–of colluding with officers of the English colonial oppressors.

The nationalist newspaper The Freeman’s Journal was the first to review The Playboy on January 28, 1907. It condemned the play as an

. . .unmitigated, protracted libel upon Irish peasant men, and, worse still, upon Irish peasant girlhood. . . . The worst specimen of stage Irishman of the past is a refined, acceptable fellow compared with that imagined by Mr. Synge, and as for his women, it is not possible, even if it were desirable, to class them. . . . It is quite plain that there is a need for a censor at the Abbey Theatre.

(In James Kilroy, The Playboy Riots (Dolmen, 1971) 7-9.)

Like most attempts to suppress creative works, the “Playboy Riots,” as they came to be known, reflected the controversies of their time and place. And in 1907 Dublin there was heated debate over what—and who—represented true Irish culture and heritage. Synge, Yeats, Lady Gregory, and the Abbey Theatre were one faction—educated, Protestant, and English speaking. But there were many who resented their cultural dominance and questioned their right to speak for the majority rural, Roman Catholic native Irish population.

It was these staunch nationalists who were incensed when Synge (who was descended from many generations of wealthy English landlords) wrote characters who seemed to embody the worst stereotypes of Irish peasantry. The foolish, drunken, and ignorant “stage Irishman” had been the butt of English jokes for centuries, and Synge’s satire seemed like just another insult.

Not all reviews of the play were negative. P.D. Kenny writing in the Irish Times, called it a “highly moral play” and admired Synge’s courage:

He has led our vision through the Abbey street stage into the heart of Connaught, and revealed to us there truly terrible truths, of our own making, which we dare not face for the present. . . . The words chosen are, like the things they express, direct and dreadful, by themselves intolerable to conventional taste, yet full of vital beauty in their truth to the conditions of life, to the character they depict, and to the sympathies they suggest. It is as if we looked in a mirror for the first time, and found ourselves hideous. We fear to face the thing. We shrink at the word for it. We scream. (Kilroy, 37-38)

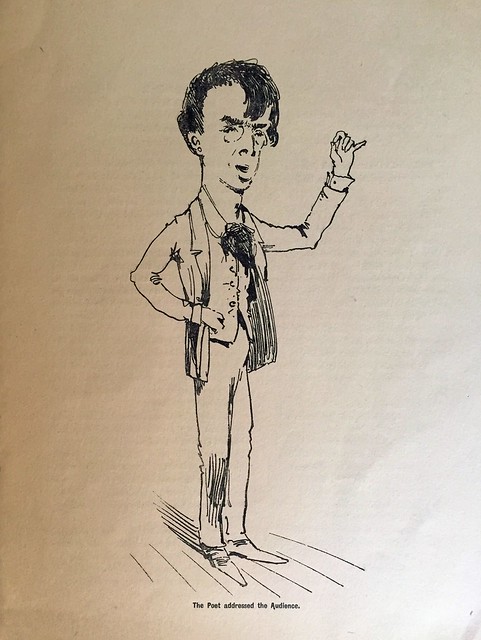

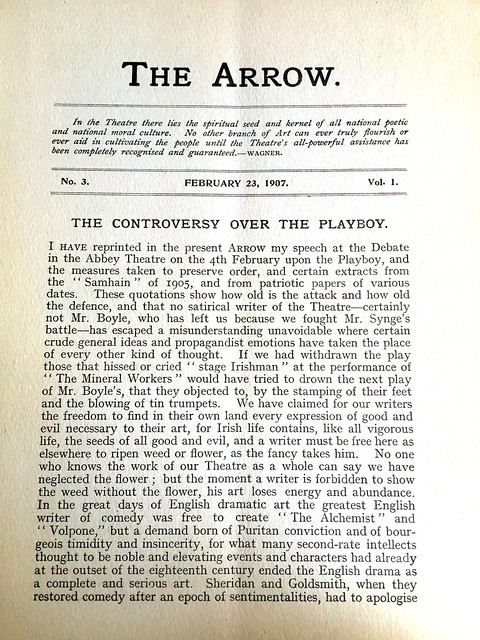

On February 4 Kenny found himself in the perhaps unenviable position of moderating a public debate on The Playboy, held at the Abbey Theatre. W. B. Yeats published his remarks of that evening in the February 23 issue of the Abbey’s magazine The Arrow. Addressing a large and unruly crowd, Yeats asserted that

I certainly would never like to set plays before a theatrical audience that was not free to approve or disapprove, even very loudly, for there is no dramatist that does not desire a live audience. We have to face something quite different from reasonable expression of dislike. On Tuesday and on Monday night it was not possible to hear six consecutive lines of the play, and this deafening outcry was not raised by the whole theatre, but almost entirely by a section of the pit, who acted together and even sat together. It was an attempt to prevent the play from being heard and judged. We are under contract with our audiences, we receive money on the understanding that the play shall be heard and seen; we consider it is our duty to carry out our contract.

(W. B. Yeats, “The Controversy over The Playboy,” in The Arrow)

His opponents countered that Yeats, by having protesters arrested, was depriving the theater-going public of its right to express disapproval. Yeats disagreed:

It has been said…that the forty dissentients in the pit were doing their duty because there is no government censor in Ireland. The public, it is said, is the censor where there is no other appointed to the task. But were these forty—we had them counted upon Monday night and they were not more—alone the public and censor? What right had they to prevent the far greater number who wished to hear from hearing and judging? They themselves were keeping the plays [sic.] from the eyes and ears of its natural censor.

(W. B. Yeats, “The Controversy over The Playboy.”

Opponents of the play were having none of it. Arthur Griffith wrote in Sinn Feinn

On Tuesday this story of unnatural murder and unnatural lust, told in foul language was told under the protection of a body of police. . . . The circumstances were appropriate, but we are sorry for the Abbey Theatre. It invited the opinion of the public upon its play, and when that opinion was unfavourable it invited the aid of Dublin Castle to crush its expression. And yet its directors talk of “freedom”. (Kilroy, 67)

The Freeman’s Journal (31 January) opined that

Surely the managers of the Abbey Theatre have by this time had enough of their police-protected drama. Mr. Yeats prophesied that his friend Mr. Synge would profit by the popular condemnation of his play through the sale of his book. In that fashion the repulsive calumny can be brought to the knowledge of all who are anxious to read it without the scandal of its public performance in Dublin. (Kilroy, 41)

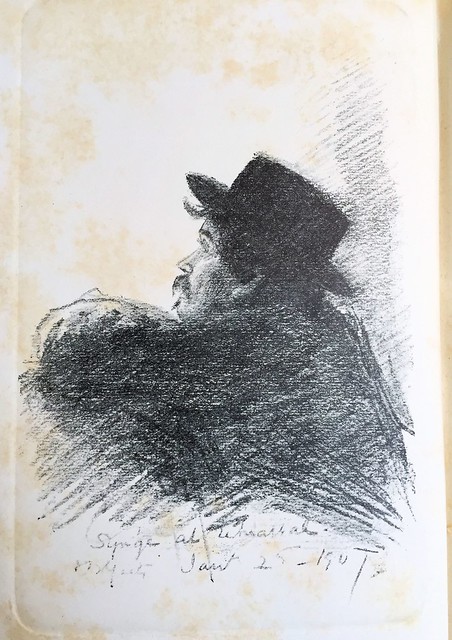

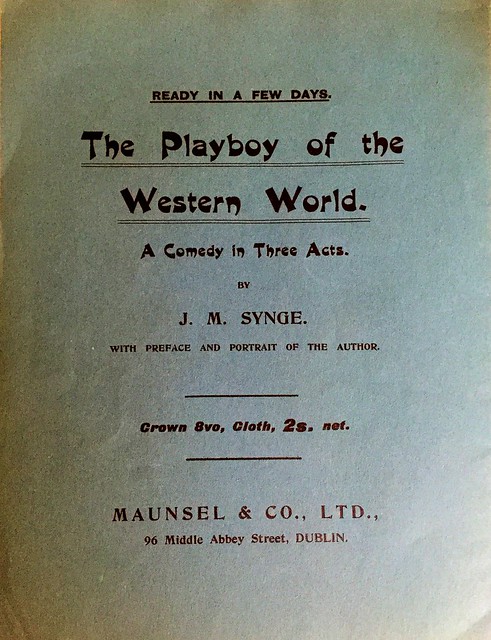

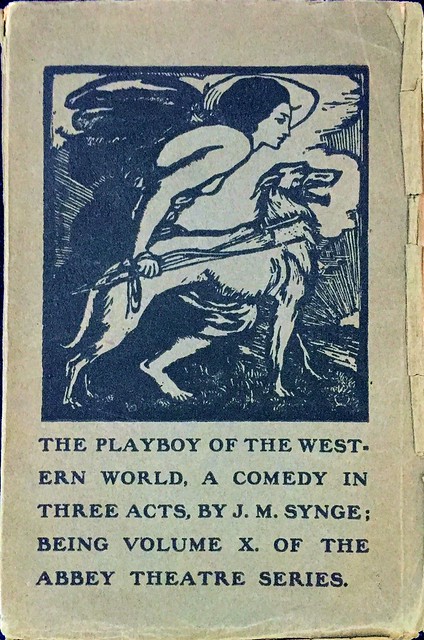

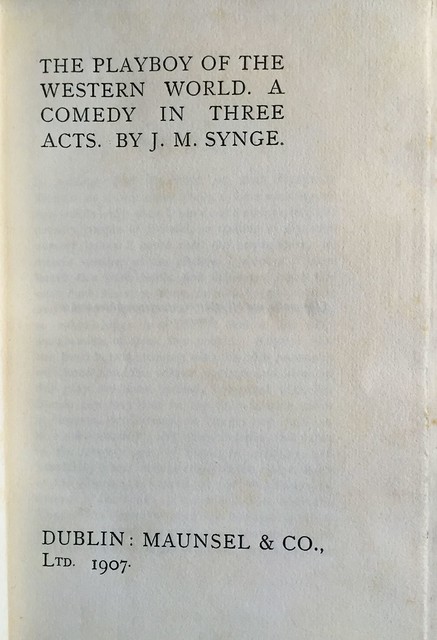

Print editions of The Playboy were indeed popular sellers in February and March of 1907. The new Dublin publishing house Maunsel & Co. published a “Theatre edition” as part of the Abbey Theatre series.

This was very soon followed by a Library Edition, which included a portrait of and preface by Synge.

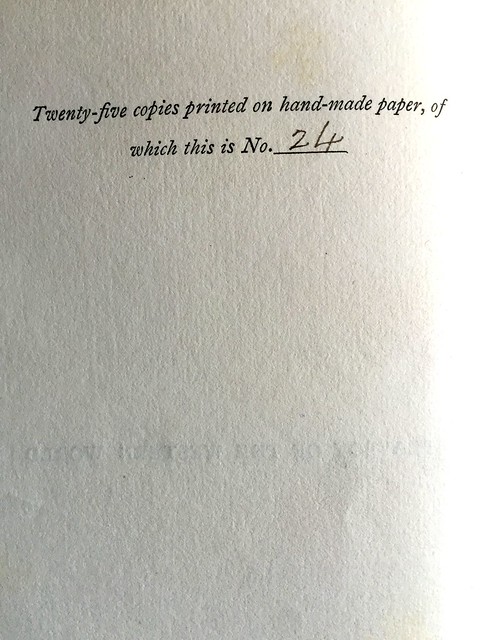

A limited edition of 25 copies on hand-made paper was also available for collectors.

In his author’s preface, Synge asserts that his play reflects the authentic language of Irish peasants, with whom he had “lived in real intimacy.”

It is not clear how closely the published editions reflect the staged versions (or attempted versions) of 1907. Synge and Lady Gregory both maintained that the text had not been extensively censored in response to the protests. At any rate, there were no attempts to ban the book versions of The Playboy. But the play again drew protests when it was staged later that year in London and then in America.

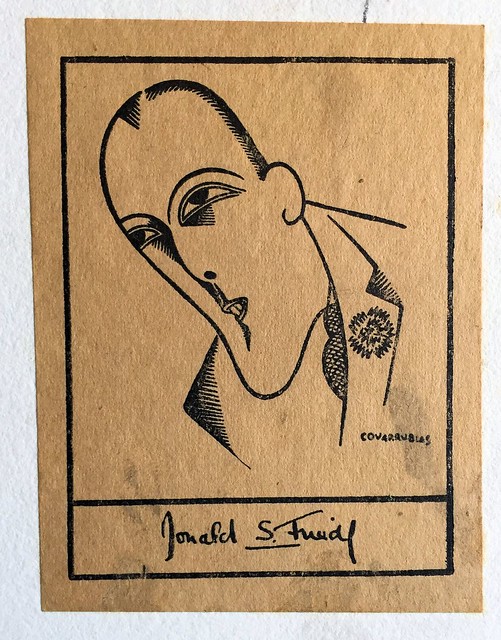

As it turned out, The Playboy of the Western World was Synge’s last completed work. Already ill in 1907, the playwright would be dead two years later at the age of only 38. But the rest of the world was quick to recognize his Playboy as a literary masterpiece, and eventually his native Ireland followed suit. Copies of the Maunsel & Co. editions became collectors’ items– ZSR Special Collections’ copy was once owned by Chicago publisher and book collector Donald S. Friede.

In some ways the Playboy controversy seems remote for a 21st century reader. Objections to onstage brawling or mentions of women’s lingerie are laughably quaint for a modern theater-goer. But many aspect of the Abbey Theatre’s dilemma are quite familiar, especially during Banned Books Week as we are made aware of challenges to texts deemed objectionable for a wide variety of reasons.

Ireland in 1907 had done away with most official government censorship—as has most of the developed world today. But then as now, questions persist about the relationship between creative works and the societies in which they exist. When does satire cross the line into class, gender, racial, or ethnic slur? Must national cultural institutions always reflect the values of their constituents? And is a vocal minority ever justified in preventing a wider audience from experiencing creative works that the minority finds disturbing or offensive?

As recent commentators have pointed out, book censorship per se does not really exist in the United States today. But we are still grappling with many of the same issues that faced Synge and his opponents in 1907.