This article is more than 5 years old.

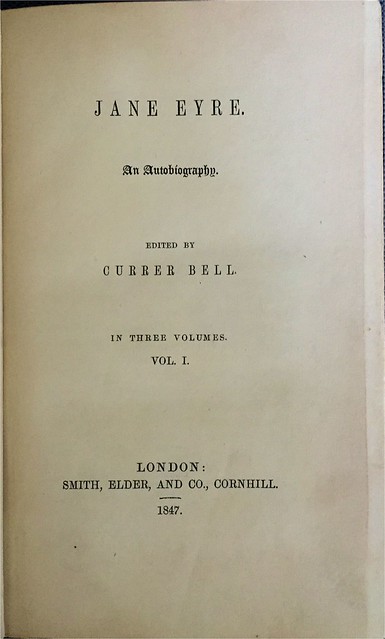

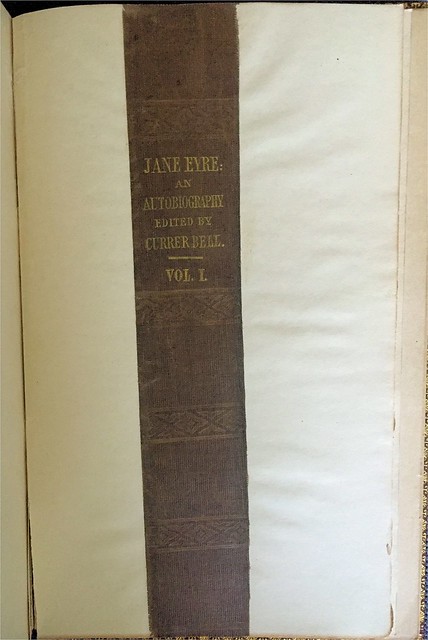

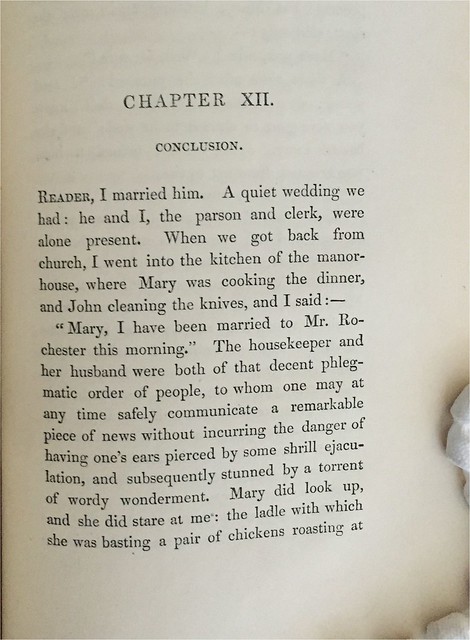

April 21, 2016 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charlotte Bronte. Her best-known novel, Jane Eyre, was first published in 1847. ZSR Special Collections’ copy of the first edition of Jane Eyre was part of Charles H. Babcock’s collection and is currently on view in the Special Collections & Archives Reading Room (ZSR625) as part of the exhibit Books and Bibliophiles at Wake Forest.

Charlotte Bronte and her sisters, Emily and Anne, are, as author Tracy Chevalier puts it, “part of the furniture that makes up the house that is Britain.”

Partly they are famous because of the sheer improbability of what they accomplished. Picture your siblings: how likely is it that you could all produce novels within the same year, which are still classics 150 years later? Not only that, but they were all women, at a time when women were not encouraged to write, much less publish.

Although the Bronte siblings began writing fiction as children, it was Jane Eyre that launched the sisters’ brief careers as published novelists.

In 1847 Charlotte and her sisters were back at home in Yorkshire after a stint as teachers in Brussels (which experience provided the inspiration for Charlotte’s later novel, Villette). After a failed attempt to start their own school at Haworth, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne turned to writing as a potential source of income. In 1846 they published, at their own expense, a volume of their collected poetry—which sold a total of two copies. Undaunted, Charlotte sent manuscripts of her novel The Professor, along with Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, to various publishers, under the gender-ambiguous pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. They met with little success at first, but when Charlotte received a rejection for The Professor from the small firm of Smith, Elder and Co., she came back with another proposal:

Your objection to the want of varied interest in this tale is, I am aware, not without grounds—yet it appears to me that it might be published without serious risk if its appearance were speedily followed up by another work from the same pen of a more striking and exciting character. . . I have a second narrative in 3 vols. now in progress and nearly completed, to which I have endeavoured to impart a more vivid interest than belongs to the Professor; in about a month I hope to finish it—so that if a publisher were found for “the Professor”, the second narrative might follow as soon as was deemed advisable—and thus the interest of the public (if any interest were roused) might not be suffered to cool. [Letters of Charlotte Bronte (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995), 535].

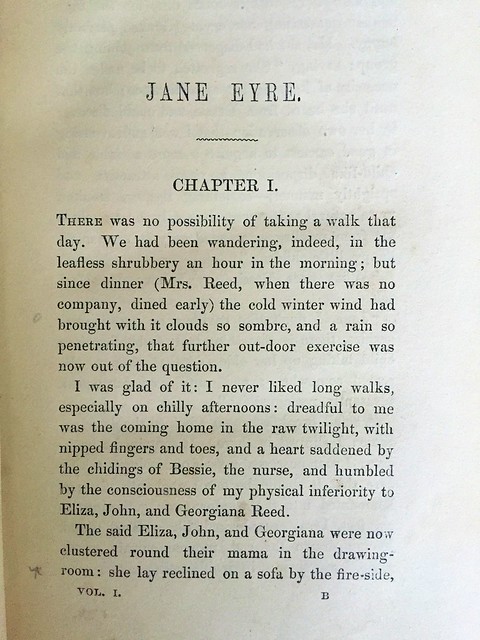

The “more striking and exciting” novel was of course Jane Eyre. Charlotte sent the manuscript to George Smith in August 1847, and the publisher’s enthusiasm was immediate.

Smith wrote to “Currer Bell” with some proposed edits to the manuscript, apparently expressing some misgivings about the early chapters dealing with Jane’s childhood. Charlotte wrote back thanking him for the “judicious remarks and sound advice,” but firmly rejecting his suggestions.

I am not however in a position to follow the advice; my engagements will not permit me to revise “Jane Eyre” a third time, and perhaps there is little to regret in the circumstance; you probably know from personal experience that an author never writes well till he has got into the full spirit of his work and were I to retrench, to alter and to add now when I am uninterested and cold, I know I should only further injure what may be already defective. Perhaps too the first part of “Jane Eyre” may suit the public taste better than you anticipate—for it is true and the Truth has a severe charm of its own. [Letters 539]

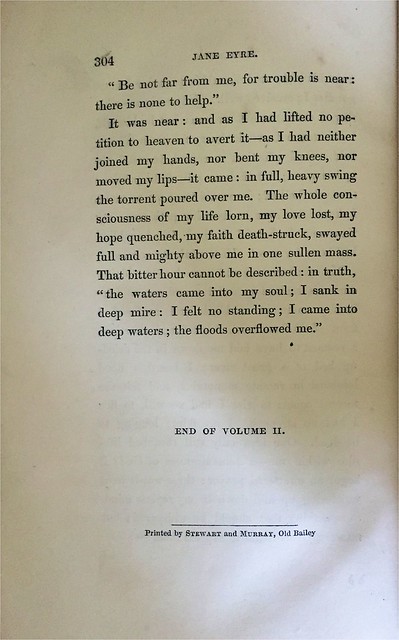

Charlotte’s judgment prevailed, and Jane Eyre was published in three volumes in October 1847. Charlotte wrote to Smith: “You have given the work every advantage which good paper, clear type and a seemly outside can supply. . . . I now await the judgment of the press and the public.”[Letters 552]

The reviews, when they arrived, were mixed. Some were very enthusiastic, but the December 1848 notice in the Quarterly Review was typical: the reviewer (Elizabeth Rigby, writing anonymously as was standard practice) took Jane Eyre to task for its “vulgar-minded”ness and unlikeable heroine, but admitted that

it is impossible not to be spell-bound with the freedom of the touch. It would be mere hackneyed courtesy to call it ‘fine writing.’ It bears no impress of being written at all, but is poured out rather in the heat and hurry of an instinct, which flows ungovernably on to its object, indifferent by what means it reaches it, and unconscious too.

This view of Charlotte’s writing (and even more so Emily’s) as the outpourings of a gifted but naïve and unsophisticated author with little control over her art is a persistent one, but it is hard to reconcile with the reality of Charlotte’s novels—especially Jane Eyre, which was written deliberately for the literary marketplace.

Another of Jane Eyre’s early reviewers was George Henry Lewes, who wrote a mostly glowing notice in Fraser’s Magazine for December 1847. But he took issue with the more sensational features of the novel, observing that it had “too much melodrama and improbability, which smack of the circulating-library.” (“Circulating library”being 19th century code popular/sensational/women’s literature; Oprah’s book club might be a modern equivalent). Charlotte felt compelled to respond, and in a letter to Lewes she pointed out, with some understandable exasperation, that her first novel (The Professor) had been a sober and non-melodramatic outing that was rejected by six publishers:

They all told me it was deficient in “startling incident” and “thrilling excitement”, that it would never suit the circulating libraries, and as it was on those libraries the success of works of fiction mainly depended they could not undertake to publish what would be overlooked there. . . . I mention this to you, not with a view of pleading exemption from censure, but in order to direct your attention to the root of certain literary evils—if in your forthcoming article in “Frazer” you would bestow a few words of enlightenment on the public who support the circulating libraries, you might, with your powers, do some good. [Letters 559]

Critics notwithstanding, sales of Jane Eyre were excellent. Its success sparked interest in the other “Bell” siblings’ writings, so Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey were published in 1848. There was much speculation about the true identity of the authors, but Charlotte worked to retain the sisters’ anonymity for as long as possible. Eventually Charlotte and Anne paid a visit to the Smith, Elder offices to reveal their true identity (in part to try to resolve a copyright dispute with the American publisher of Wuthering Heights).

The sisters had little time to enjoy their celebrity (or not, in Emily’s case). Both Emily and Anne were dead of tuberculosis within two years. Charlotte published two more novels, Shirley and Villette. But by 1855 she too was dead, at the age of 39. Elizabeth Gaskell’s posthumous biography, published in 1857, sparked a public fascination with the lives of Charlotte and her sisters that is still going strong. Jane Eyre continues to be the most widely read Bronte novel, a perennial favorite on English Lit reading lists, and the subject of many stage and screen adaptations and literary homages, prequels, and sequels.

4 Comments on ‘Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte (1847)’

I enjoyed this very much. _Jane Eyre_ was my favorite novel through high school and college, until Jane Austen intruded in a major way!

Thank you for sharing this, Megan! Jane Eyre is still one of my favorite novels, and I went to the live stream of the National Theatre’s production of Jane Eyre earlier this month at the Hanesbrands Theatre: http://ntlive.nationaltheatre.org.uk/productions/51859-jane-eyre It is a story that has certainly stood the test of time and still has much to say.

Thanks for the history lesson. It was very interesting to read of the circumstances surrounding this publication!

I loved the comparison of the circulating library to Oprah’s book club!