This article is more than 5 years old.

This ABCs blog post was written by Nancy Sullivan, Volunteer in Special Collections & Archives.

L is for…

Laurence Stallings Papers

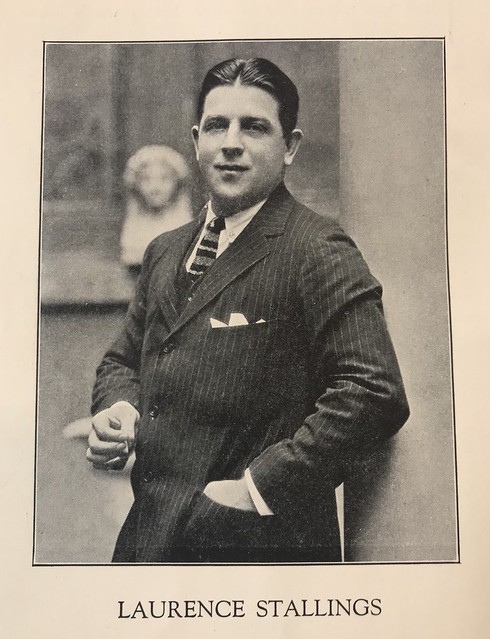

Having a prolific writing career that spanned five decades and a most interesting and accomplished life, one quickly concludes that a blog post about Laurence Tucker Stallings can only be a “tip of the iceberg” attempt at introducing this fascinating man and alumnus of Wake Forest.

Born November 25, 1894 in Macon, Georgia, Laurence Tucker Stallings was the youngest child of Larkin Tucker Stallings, a bank teller, and to Aurora Brooks Stallings a homemaker. It was Stallings’ mother who is credited with first introducing Laurence and his two older siblings (George Brooks Stallings and Ruth Stallings) to the world of literature. Laurence graduated from Gresham High School in Macon, Ga. in 1911, and following his graduation he went to work for the Royal Insurance Company of Atlanta. With the help of a Baptist minister and family friend, Rev. John E. White, Stallings received financial aid that enabled him to enroll at Wake Forest College in the fall of 1912.

Once at Wake Forest, Stallings became an active member of the Wake Forest community where he served as editor of the campus newspaper the Old Gold & Black. Stallings left Wake Forest in 1915 to return to Georgia to work as a reporter for the Journal. His return home put Stallings back in his home community that was richly steeped in military history from the Civil War. This influenced Stallings to join the National Guard unit of which his father was a member. In 1916, Stallings returned to Wake Forest, graduating later that year with a major in Classics.

While he was a student at Wake Forest (1912-1916), Stallings met and fell in love with Helen Purefoy Poteat, the daughter of Dr. William Louis Poteat, the president of the college from 1905-1927. Helen Poteat was born in Wake Forest, NC, April 6, 1896 while her father was a professor of biology, and she soon became a “campus fixture” of the school. So it is no surprise that Stallings, with his “winning smile … and (his) soft Southern voice” would win Miss Poteat’s heart during his time at Wake Forest. The two would eventually marry, and have two daughters. The marriage ended in divorce in December of 1936.

One month after America’s entry into World War I (April of 1917), Laurence Stallings joined the United States Marine Reserve on May 29th,1917. On July 25, 1917 he was assigned to active duty in the Marine Corps as a Second Lieutenant. In the spring of 1918, Stallings and his US Marine Second Division set sail for France. Upon their arrival to France in June,1918, Stallings and his comrades were sent to Chateau Thierry to join the raging battle against the Germans at Belleau Wood.

On June 26,1918, while fighting at Belleau Wood, Laurence Stallings was leading an assault on a machine gun installation when his right knee cap was blown off. Despite his wound, Stallings was able to deliver a grenade which proved to eliminate the enemy position. In a letter written from his hospital bed three days after his injury Stallings describes “I was shot by machine gun fire in the right knee while going ‘over the top’ the other day and have a nasty, uncomfortable wound which will keep me on bed in splints for perhaps two or three months. No one can tell the outcome of my injury. I hope for the best but may be crippled. It was a real experience. We attacked for the third time, a nest of boche machine guns concealed in a deep wood … it was discovered that the devils were still operating one gun which imperiled our lives. Four of us went out to get it, crawling indian fashion, when I got mine. I lay on my back under its fire for an hour fearing to move, but gradually crawled to safety in a ravine and back to our lines.”

The Battle at Belleau Wood raged from June 6 – July 1, 1918, with June 26 marking the end of one of the most important and legendary battles in US Marine Corps history. This was a battle that exemplified the Marine Corps’ core values of honor, courage, and commitment. It was a battle that catapulted the Marine Corps to worldwide prominence. Belleau Wood was the first large-scale battle fought by American soldiers in WWI, and over the last 100 years, this rural forested battleground has remained an important pilgrimage sight for US Marines.

Stallings would spend eight months in a French hospital recovering from his leg injury. His heroic actions at Belleau Wood would win Stallings the Silver Star awarded by the US Government, and the Croix de Guerre by the French Government. Like so many soldiers from the Great War, Stallings returned from WWI deeply impacted by his war experiences, and his time on the Western Front proved so pivotal for Stallings that a great number of his professional writings would focus on war themes.

Following the end of WWI, Stallings became a reporter, critic, and entertainment editor at the The World newspaper. In 1922, Stallings suffered a fall on ice which required his injured leg to be amputated. While recuperating at Walter Reed Hospital, he began writing his novel Plumes, which would be the only novel Stallings would ever write. Plumes, which focuses on the aftermath of the Great War, reveals the personal trials of soldier, Richard Plume, who returned home disabled and disillusioned. Set in the post-war world, crippled Richard Plume comes home to find a changed world. Richard is faced with the inevitable struggles and endless consequences of war, just as Stallings himself had to face. Richard Plume ultimately concluded “all wars are criminal and never worth the cost and suffering.”

Stallings’ Plumes was described as “a great story…. it is written with dynamic power. It sets forth the wickedness and folly of war in its true colors. It lays bare the greed, the utter selfishness and the brutality of war with tremendous clearness and force.” Plumes almost won the Pultizer Prize for fiction in 1924, and it was so immediately well received that it required eight printings in the first six months after its publication in 1924. Despite its popularity, Stallings refused additional publication of the book after 1925.

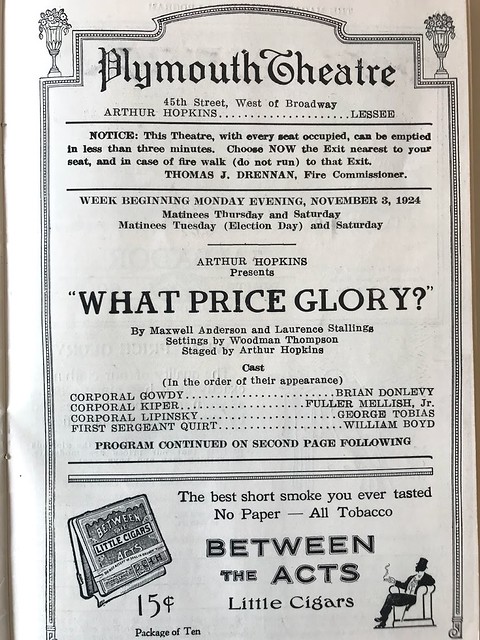

In 1923, while a theatre reviewer for the New York World newspaper, Stallings became acquainted with the playwright Max Anderson and his first play, White Dessert. The two developed a friendship and ultimately they co-wrote the long running play, What Price Glory. Produced by Arthur Hopkins, What Price Glory opened at the Plymouth Theatre in New York City in 1924, and it ran for 433 performances.The huge success of the play elevated Stallings to a point of great notoriety as a writer.

What Price Glory, “has been called the American theater’s most memorable war play.” Leonard Hall, a theatre critic of the time wrote, “a magnificent play magnificently played.” Alexander Woollcott wrote, “no war play written in the English language since the German guns boomed under the walls of Liege, has been so true, so alive, so salty, and so richly satisfying as the piece called What Price Glory.”

Stallings continued his collaboration with Anderson, and the two co-wrote the plays, First Flight which and The Buccaneer, both in 1925. Neither of these plays garnered the acclaim that What Price Glory had, so the partnership between Stallings and Anderson was dissolved. Laurence Stallings continued his writing for both theatre and screen producing the musical ”Deep River” (1926), screenplays “Old Ironsides”, “Northwest Passage,” “The Jungle Book,” “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon,” and “Miracles Can Happen.” Stallings collaborated with Oscar Hammerstein on “Rainbow” and he wrote the stage adaptation of “A Farewell to Arms”.

By 1925 (at the age of 31) it was written that “Laurence Stallings has achieved brilliant success in three literary fields. He is co-author of What Price Glory, the big dramatic hit of 1924-1925: he published a novel Plumes of outstanding quality: and he is the always arresting penman behind his famous newspaper department, “The First Reader” in the New York World. Stallings’ amazing success has been achieved in spite of years in the Marine Corps, hard fighting in the decisive Belleau Wood action, and months spent in hospitals as a result of serious wounds. Nothing seemed to daunt his splendid vitality and he even wrote books and stories on his hospital bed.”

It is now believed that Stallings worked on both his novel, Plumes and the play, What Price Glory at roughly the same time, and possibly from his hospital bed at Walter Reed Army Hospital following the amputation of his leg. Plumes served as Stallings’ inspiration for the very successful silent film The Big Parade, released in 1925. One critic wrote at the time of the release, “The Big Parade represents the finest, most beautiful and most moving drama to be found anywhere on either stage or screen. It is easily the best film ever made.” The film would become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s largest grossing film until Gone With the Wind in 1939. Many years after the movie’s release it has been written “in terms of cinematic history, The Big Parade is regarded as one of the finest and most influential films about the First World War and a classic of the silent era.” It was “The Big Parade that allowed Stallings to earn a place as a highly productive screenwriter” and between 1925 and 1953 he produced some eighteen scripts.

In 1933 Stallings compiled another type of book where he wrote brief captions for several hundred photographs showing all aspects of World War I. The book, The First World War: A Photographic History, has been regarded as the thing “that pointed the way to a new kind of photojournalism.”

Laurence Stallings served in WWII as a Lieutenant Colonel. He was chief of the Interview Section of the US Marines. Completing this second wartime commitment with the Marines, Stallings was then under contract with MGM Studios where he authored and co-authored several John Ford films including Three Godfathers (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and The Sun Shines Bright (1954).

In 1963, during what reviewers refer to as “a World War I revival”, Stallings published what would be his last book The Doughboys: The Story of the AEF, 1917-1918. Without losing focus on the facts of history, Stallings was able to “summon up details (of his wartime experiences) and write how the weapons and equipment worked or didn’t: how the uniforms fit and felt: what they had to eat and how it tasted: how the wounded were treated and mistreated … paying full attention and honor to the average American soldier, the Doughboy.”

In 1968, following a brief illness, Laurence Stallings died of a heart attack and was buried with full military honors at Fort Rosencrans National Cemetery in California. In his obituary it was written “the burly 6-footer was known to acquaintances as genial and friendly.” Looking at Stallings’ writing career it was written, “taking his work in all forms as a single whole, Laurence Stallings has done more than any one American author to cut away the romantic glamour of war and to expose its wretchedness.”

Many years after his death, when the University of South Carolina Press re-published Stallings’ book, Plumes (2006), George Garrett’s preface says, “The voice of Laurence Stallings is an authentic American voice and what he has to tell us is as fresh and dismaying as this morning’s headlines.” Garrett continues to describe Stallings “as an active recorder of his times and as a wounded witness to the almost constant warfare of the twentieth century, he demonstrated a mastery of these several distinct literary forms to make his statement, to send his message loud and clear.” Stallings had a “passionate and obsessive concern with the horror and futility of war. His position on war was not that of a pacifist.

A close friend wrote, “he hates war, he loathes it. Not because of what it has cost him, but because history has taught him that his son and his son’s son will tread the same path into the yapping maw of the war god.” Stallings knew, “youth, eager as ever, follows the flag down the village street.”

To learn more about Laurence Stallings, you can look through his manuscript collection housed in Special Collections and Archives. Email archives@wfu.edu to make an appointment.

L is for Lou Rogers Wehlitz Papers

Lou Rogers Wehlitz could be considered an elusive soul, but it was once written “life for Lou Rogers Wehlitz, has been literature. As a collector. As a teacher. As author. As editor. As poet.” Throughout her life Lou Rogers Wehlitz was very aware she was not well known in literary circles, but she felt very satisfied and rewarded even though she did not have notoriety. The process of writing was her great joy. She once said, “writing for me is an urge. It’s something I’ve got to do … it’s always been something I do for enjoyment, and that’s how it should be.”

Researching Wehlitz’s life and literary career is like taking an adventure where one discovers rich rewards at every turn. Wehlitlz wrote for six decades and during that time she published 400 works which include educational and religious articles, biographical sketches, human interest stories, children’s fiction, historical pieces and poetry. She wrote three books, Tar Heel Women’ (published in 1949) which features short sketches of 39 influential women throughout NC history, two of which are Dolly Madison and Mathilda McNeill Whistler (mother of painter John Whistler). Wehlitz’ second book, The First Thanksgiving (published in 1962) which is a children’s story, she wrote while she was working as a textbook editor in Chicago. Memory Is a Star was her last book, is a collection of Wehlitz’s poetry dedicated to her late husband, H.F. Wehlitz who died in 1964. In an interview given in 1984 Wehlitz professed the books she wrote were her greatest accomplishment.

Lou Rogers Wehlitz did exhaustive research to compile her books, articles, and publications. She did a series of articles about men and women who were pivotal in shaping our NC history for the magazine We The People. These biographical writings included both well known and little known folks that were instrumental in shaping the state of NC. Wehlitz used her masterful skill with words to make these historical biographies well worth reading. Within the Lou Rogers Wehlitz Papers, house in Special Collections & Archives, it is fascinating to see all the stages of her writing process from her manuscripts, to letters where Wehlitz wrote requesting information on particular historical figures, to the response letters that Wehlitz received sharing information and insights and finally, to the completed publications.

As I have become acquainted with the collection of Lou Rogers Wehlitz’ papers, one thing has been both interesting and striking. Although biographical writing is a large part of her body of work, her collection of papers here at ZSR contains virtually no biographical information on Wehlitz’ life. From an interview written about Wehlitz in a Fayetteville, NC newspaper in 1984, when she was 77 years old, we learn she was born in Hope Mills, NC (circa 1907). The only other bit of biographical information on Wehlitz that can be found in her collection is a poem she wrote for a newsletter at Brookridge Retirement Center in Winston-Salem. So we would assume that the final days of her life were spent here. Given we have no details on her family, or her education, we do know Wehlitz’ extensive writings speak to her deep love of the written word, her deep love of her home state and the people of North Carolina.

L is for Library Record Group, Director’s Office, Ethel Taylor Crittenden

The history of the Zachary Smith Reynolds Library (ZSR Library) is most likely a topic that is very rarely thought about, but for this letter L blog post I’ve chosen to delve into the Library Record Group papers (Library Record Group, Director’s Office, Ethel Taylor Crittenden). This blog post focuses on some early history of ZSR as well as a look at the librarian whose 28 year career significantly impacted the growth of the library making it what it is today.

First, a brief look at the history of the early years of the Wake Forest Library is important. For the first forty or so years after Wake Forest College’s founding in 1834, the school did not have an official library. In 1879 the Heck-Williams Library opened on the old campus in Wake Forest, NC. Prior to the library’s opening, the Philomathesian and Euzelian literary societies on campus maintained libraries for their members, and in the History of Wake Forest College it was written that in 1866, each literary society had about 4,000 volumes, many more than they had room for on the shelves, so that many were lying in piles on the floor. As the Heck-Williams Library building was being completed, the school’s Trustees voted on March 1, 1879, that “Halls in the new building are tendered to the Societies on condition that the books of the two libraries be consolidated into one general library, which library shall be under control of the Trustees of Wake Forest College for the benefit of the two Societies and others as they deem best.” This proposition was promptly accepted by the Societies. Faculty and students were in charge of the shelving and classification of the books, as well as serving as superintendents of the Reading Room. It was not until September, 1908, that the appointment of a regular librarian, Mr. E. P. Ellington, took place. From 1908 to 1911 Mr. Ellington did the accessioning and cataloguing of books. In 1911 Miss Louise P. Heims, a trained librarian, began doing the job of cataloging. During her time at the library, Miss Heims greatly improved the catalogue, adding many cards and making it a dictionary catalogue with title cards for most books. In January 1915, Miss Heims left her position as librarian at Wake Forest and Mrs. Ethel Taylor Crittenden assumed the role as college librarian.

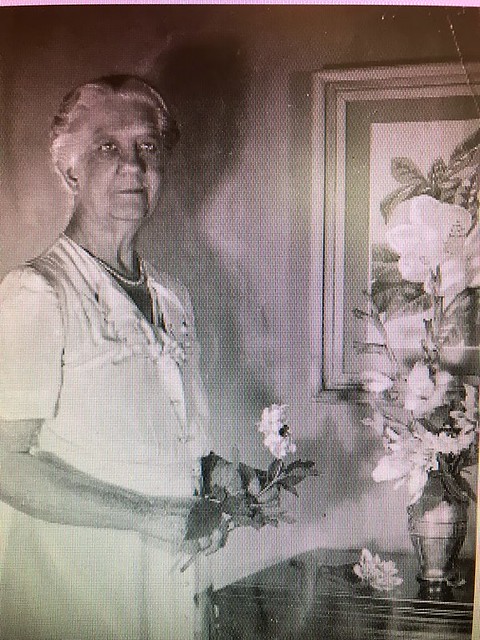

The third of seven children, Ethel Taylor Crittenden was born in Wake Forest, NC on February 7, 1881 to Dr. Charles Elisha and Mary Hinton Taylor. Ethel’s father had joined the faculty of Wake Forest College in 1870, and was elected to be its sixth president in 1884. Ethel Taylor spent her childhood on the campus of Wake Forest and it was there she met her husband, Charles Christopher Crittenden. Dr. Crittenden came to Wake Forest to teach Pedigogy (Education) and Ethel attended some of his lectures. Ethel and Dr. Crittenden began dating and with their romance blossoming, the two married in 1901 when Ethel was twenty years old. Their life together was brief, as Dr. Crittenden died from rheumatic fever when he was not quite 31 years old in 1903.

Like her father, Ethel Taylor was very cultured, quiet, and retiring, and when she became the Wake Forest librarian “she was known as no ordinary librarian because she was so well-read.” Apparently this was a rarity among librarians at the turn of the century. Although Ethel developed a love of literature at a young age, and was a graduate of Oxford Seminary and Meredith College, she had very little special training in library work. She quickly educated herself in library studies by attending approved library schools during her summer vacations.

Prior to 1901, the Wake Forest library had no card catalog for its 15,000 books but the cataloging was complete by 1904. Prior to Mrs. Crittenden’s arrival on the job in 1915, great strides had been taken in both the accessioning and cataloging of books. Once she came to the library, Mrs. Crittenden and her 5 student assistants continued with the cataloging but by 1924 the need for a full-time cataloguer had become imperative. Mrs. Crittenden’s position as librarian had been so taxing that it was necessary for her to spend the entire school year of 1925-26 in recuperating her lost strength, and during this period the cataloger resumed Mrs. Crittenden’s duties.

With her return to work, Mrs.Crittenden gave focus to her efforts and created the Rare Books Collection in the library. She was quite interested in rare books and in order to fund their purchase she founded the “Friends of the Library.” The members made gifts of books or money, and the money enabled the purchase of collections of books and pamphlets.

In the History of Wake Forest Vol III (pages 158-173) there are extensive listings of the collections secured by Ethel Crittenden for the growing Wake Forest Library. Mrs. Crittenden was responsible for (securing) many of the distinguished books in the Wake Forest Library, particularly the vast collection of NC Baptist Historical materials. In 1970, the Wake Forest University trustees named the collection “The Ethel Taylor Crittenden Collection in Baptist History.” “By her untiring interest and industry she has had a chief part in the development of the Baptist collection to be the best in the South.”

The other area that Mrs. Crittenden focused her collection efforts toward were history books for what is now the NC Collection. It was written about Mrs. Crittenden that she “has done invaluable service in building up the special collections … and in securing others. The Baptist Collection, the NC Collection as well as the rare books collection of ZSR Special Collections and Archives exist thanks to the exhaustive work of Ethel Crittenden and her long career as librarian at Wake Forest that spanned from 1915 to 1943.”

At the time of her retirement, Ethel Crittenden continued living in Wake Forest, NC. Nine years prior to her death it was written “Mrs. Ethel Taylor Crittenden is in every sense of the word a lady. She enjoyed reading and writing passionately until her eyesight and hearing began to fail. Her life is a perfect example of genteelness and humility. Although she has retired officially from Wake Forest College, her presence remains as an incentive to all who know and love her.” On February 7, 1983, Ethel Taylor Crittenden died at the age of 102, and her legacy continues on within the walls of the existing ZSR Library. Crittenden’s long presence as the librarian of Wake Forest unquestionably impacted the exponential growth of the library’s collections, making the ZSR the respected hall of learning that it is today.

Stay tuned for M!

If you are interested in looking through any of the collections in Special Collections & Archives, please email archives@wfu.edu for an appointment.

3 Comments on ‘ABCs of Special Collections: L is for…’

Thank you for these interesting and informative reports, including the reminders about the origins and history of the ZSR Library.

Thank you, Nancy, for this informative blog post and your time and effort dedicated to our collections. I like hearing more details about the names I see every day and learning more about their impact on Wake Forest!

Enjoyed learning from these “L” entries!