This article is more than 5 years old.

A couple of weeks ago, I flew out to Denver for LITA Forum. By the way, the options for flying from Charlotte (major American Airlines hub) to Denver (major United hub) are pretty meager, so if you want to know what Highway 52 is like at 4:45am, I can tell you!

As a recent LITA president, I was gratified to see attendance was up for the third year in a row – about 30% higher than the 2014 meeting. It’s a very productive, manageably sized conference about technology in libraries, and more people should go – and present (I’m looking at several of you…).

Last week, I was at the CNI fall meeting, which is always a densely packed day of high-power meetings on application of technology in academic and research libraries. These two meetings always fall almost back to back (relative to the speed at which I write conference reports), so I get to compare them for overall trends and report on them jointly.

Trend 1: You Aren’t Changing the Physical Space in Your Library Fast Enough.

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”

—The Red Queen, Through the Looking Glass

Denver’s Auraria Campus is a single site that is home to three collocated institutions of higher ed, all sharing one library. The Auraria Library is nearing the end of a six-year cycle of renovations that have largely reinvented the library space, eliminating physical barriers at service points (so, no actual desks at reference and circ), putting a lot of thought into traffic flow (multiple entrances and exits with non-cattle chute security gates), and self-service technology, including a no-hassle video wall (in a very visible public area, but with a way to seat a class of about 20), self-service checkout, and self-service check-in (with a device that e-mails you a receipt and auto-sorts incoming books for main stacks and for reserves – returned reserve items are back on the shelf in minutes).

Purdue recently opened a new 164,000 sq ft building that combines their science and engineering library with multiple active learning classrooms, a 300-seat performance space (absolutely forbidden for use as a lecture hall), a data visualization lab, a gallery and exhibits (the site was previously a 1920s power plant in which many generations of engineering students did internships – lots of old equipment has been preserved), and a cafe. A standing rule is that after 5:30pm all classrooms become open study space. As a but of technology future proofing, the building wifi was constructed to support 2.5 connections per user (1.8 is pretty standard today).

Temple University is currently constructing a new library that will put about 80% of its previous main stacks collection into an automated retrieval facility, similar to the NCSU Hunt Library. They didn’t present a lot of information about the building itself, but focused on how their discovery services will have to change to support searching, browsing, and serendipity in finding the books that used to be on open shelves.

Trend 2: Second Wave Repository Planning – Now With Preservation!

A year ago, there was a lot of pessimism about whether institutional repositories had been a failure. This year, there is at least cautious optimism that there is a future there, but with a lot of work to do. One of the big concerns is that we’re putting a lot of content in a lot of silos (“the” IR, other repositories on campus, discipline-specific repositories, regional or national repositories), and as a result, we have really put ourselves in a tough spot in regards to discovery and preservation. And then there’s the issue of a major repository platform (Bepress’ DigitalCommons) being bought by Darth Vendor.

At CNI, librarians from Stanford and the University of Florida reported on their approaches to improve access and discovery in their repositories; librarians from Northwestern reported on managing preservation responsibilities when repository material goes into national systems; and with the program title of the year (“Beprexit: Rethinking Repository Services in a Changing Scholarly Communications Landscape”), presenters from Penn discussed their firm but decisive move off of DigitalCommons, and how they are taking this as an opportunity to move forward with repository improvements they have wanted for a while now.

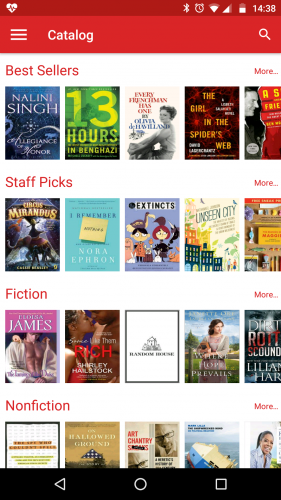

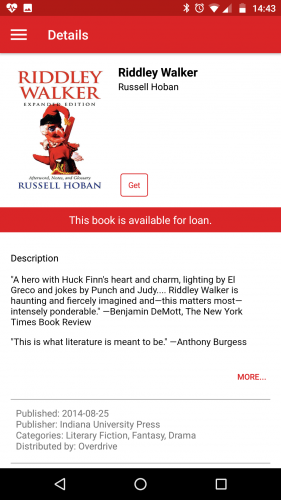

Trend 3: The E-Book Experience in Libraries Sucks, But Maybe Doesn’t Have To.

Ever get a book from Amazon to read on your Kindle, or from Google Play Books to read on a tablet? Simple, right? Now try to do the same with any e-book from your public or college library. Multiple sites, multiple logins, multiple apps to download (if app-based reading is even an option)… The New York Public Library has documented the painful 17-part process one of their e-book vendors foists on users; the library at Columbia University works with a vendor that thinks the way to distribute an e-book is as a zip file containing one PDF for each chapter. [Insert Sideshow Bob noise here.]

I’m seeing a program called SimplyE show up in a lot of places. In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, the Queens Public Library received free tablets to loan out, and decided to work on a custom interface to help find e-books (NYPL currently offers over 300k e-books). They’ve gotten enough buy-in from vendors, and IMLS money, to be able to pull metadata streams that can be loaded into a catalog or used to populate a web portal or app; and they’ve built an open source app for iOS and Android (and it’s seriously good).

On the back end, they’re getting uniform usage data, so assess that. Now they’re working with other libraries, including Amigos and Minitex (Minnesota public libraries), and Columbia and NYU to expand the idea into academic libraries. I’m really hoping this takes off in a big way.

6 Comments on ‘Thomas in Denver/DC for LITA/CNI’

Really interesting trends! Thanks for the report, Thomas!

I would love to see renting academic e-books made easier! Great to hear that IR discovery and access is improving, too. And Darth Vendor, lol.

Enjoyed your report immensely!

Thanks for all of these great highlights!

I will never be as cool as you Thomas. I hope one day to be able to read through a conference report without doing at least one side internet search to see what the heck that meant. But you do always make me WANT to do those searches so I come away with way more than just a conference report. Thanks for this; it was entertaining and enriching.

Darth Vendor! HA! Funny – and scarily apt. I am encouraged, though, to hear that others are seeing a future for IRs, albeit with new foci. I hope that is our future for WakeSpace, especially with the addition of the Digital Curation Librarian this spring…