This article is more than 5 years old.

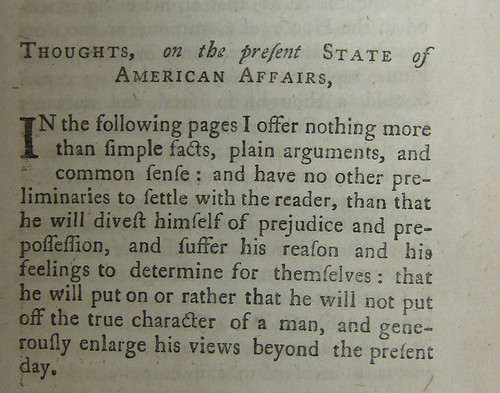

Volumes have been written on the subject of the struggle between England and America. Men of all ranks have embarked in the controversy, from different motives, and with various designs; but all have been ineffectual, and the period of debate is closed. Arms as the last resource decide the contest; the appeal was the choice of the King, and the Continent has accepted the challenge.

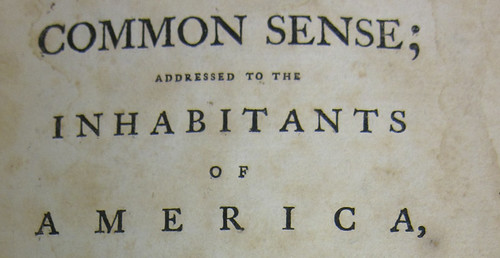

Thomas Paine, Common Sense

Thomas Paine’s 79-page pamphlet has achieved a mythic status in the history of the American Revolution. Paine often gets credit for more or less single-handedly galvanizing the reluctant colonists to commit to the war of independence. As one historian puts it “Common Sense swept the country [sic] like a prairie fire,” and “as a direct result of this overwhelming distribution, the Declaration of Independence was unanimously ratified on July 4, 1776.” [Gimbel, 57]

This may be overstating the case a bit. Paine’s pamphlet was certainly popular and influential in revolutionary America, but the real story of Common Sense‘s creation, dissemination, and reception is less straightforward– and perhaps more interesting– than the myth.

Thomas Paine was born to a Quaker family of modest means in Norfolk, England in 1737. His formal education ended when he was 12 years old, after which he pursued various occupations without great success. In 1774 he emigrated to Philadelphia, where he soon took on the job of editing Robert Aitken’s radical new monthly newspaper, the Pennsylvania Magazine. Paine loved controversy, hated the British aristocracy, and was devoted to the Enlightenment ideal of individual liberty. So it comes as no surprise that he was an immediate and vocal supporter of American independence.

In October 1775 King George III gave a speech to Parliament in which he declared that the American colonies were in rebellion against the crown and therefore subject to military intervention. Paine wrote a response to the king’s pronouncement, for which his friend Dr. Benjamin Rush suggested the title Common Sense.

Paine had originally intended Common Sense to appear in newspapers in several installments, but he realized that his argument was more convincing when taken as a whole. So he contracted with Philadelphia printer Robert Bell to publish the work.

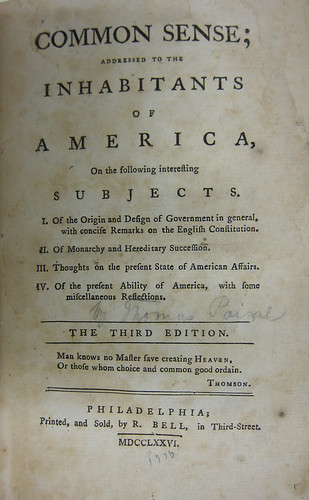

Wake Forest’s copy of Common Sense is Bell’s third edition, published in February 1776.

Common Sense was first published on January 9, 1776. This first printing consisted of 1000 copies, with profits to be split evenly between the author and publisher. By January 20 Bell was advertising a “new edition” in press, which likely means that the first printing had already sold out.

Paine had already publicly announced a plan to use his share of the profits from Common Sense to buy mittens for the Continental Army in Quebec. However, Robert Bell insisted that printing costs had eaten up all the profits from the first edition and that he owed Paine nothing. A very public feud commenced between Paine and his publisher, with accusations and counter-accusations printed in the Pennsylvania Evening Post.

Bell published his unauthorized “second edition” (really just a reprint of the first edition) on January 27. Paine meanwhile contracted with printers Thomas and William Bradford to publish, at the author’s expense, a “new edition” with “large and interesting additions by the author” and a response to Quaker objections to a military rebellion. The Bradford edition was published in February and sold for half the price (one shilling) of Bell’s.

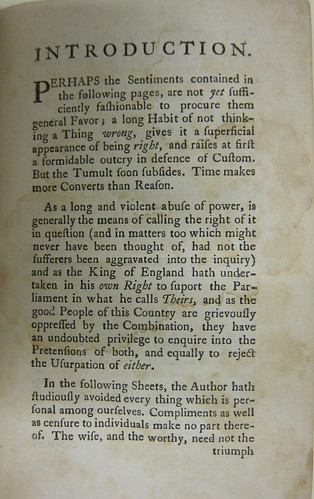

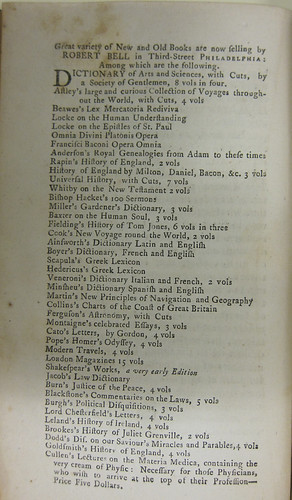

A publisher’s advertisement from Bell’s 3rd edition of Common Sense gives an idea of the reading habits of Philadelphians in 1776.

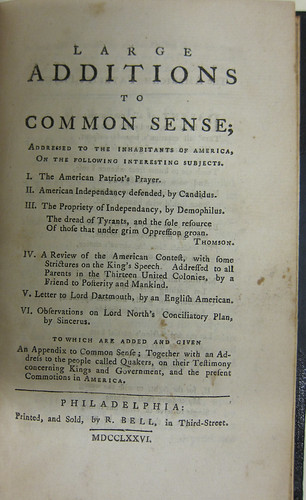

Undeterred, Bell produced a third edition that not only pirated the additional materials from the Bradford edition, but also included a section called “Large Additions to Common Sense,” which reprinted several pieces by other authors. Paine was predictably incensed by this and published another denunciation in the Post, to which Bell then responded in kind.

Despite–or more likely, because of– this feud, copies of Common Sense continued to sell briskly in Philadelphia.

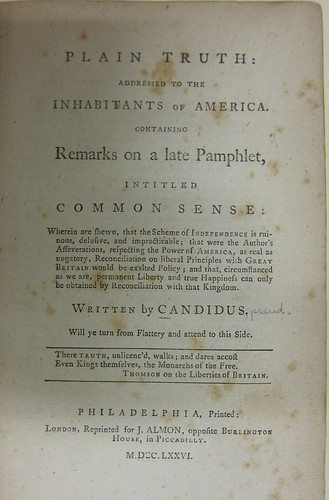

There were many loyalist rebuttals of Common Sense. One of the earliest and best known is Plain Truth: Addressed to the Inhabitants of North America, written by Maryland planter James Chalmers under the generic pseudonym Candidus.

Wake Forest’s 1776 London edition of Plain Truth

Both Bell and Bradford published several more editions of Common Sense in 1776, and it was also reprinted by dozens of publishers in North America and eventually in Europe. But there is no way to know how many actual copies were produced. Thomas Paine made various claims that 100,000 to 150,000 pamphlets were printed and distributed in the first months of 1776. But he had no evidence for these very large figures (a sale of 150,000 copies in three months in colonial North America would be comparable to a modern Harry Potter book release), and it seems likely that the actual numbers were considerably lower. And since Common Sense was published only once south of Philadelphia (in Charleston), it is also likely that the North American distribution was concentrated in the urban centers of New England. A close look at the dissemination and reception of Common Sense suggests that its influence was strongest among people who were already sympathetic to the revolutionary cause [Loughran, 13].

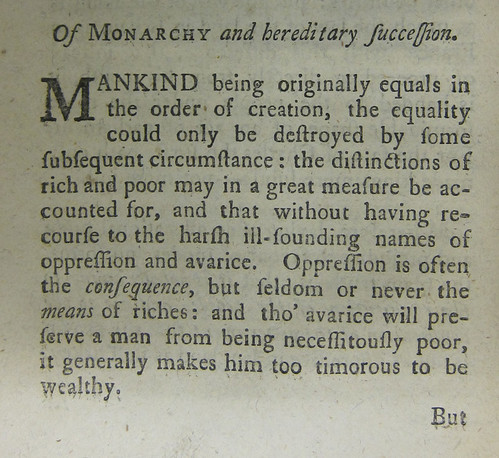

But if Common Sense is not necessarily the book that sparked a revolution, it is certainly the book that came to symbolize the American Revolution for later generations. One need only read a few pages of Paine’s pamphlet to see why this is so.

Paine’s gift for rhetoric, his persuasive power, and his ability to make complex ideas accessible to any audience have ensured his status as an American icon. And our 1776 copy of Common Sense– stained, dog-eared, and hastily printed on cheap paper– is a tangible link to the birth of the American republic.

Sources

Gimbel, Richard. Thomas Paine: a Bibliographical Check List of Common Sense with an Account of its Publication. New Haven: Yale U.P., 1956.

Gilreath, James. “American Book Distribution,” in Needs and Opportunities in the History of the Book: America, 1639-1876, David D. Hall and John B. Hench, eds. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1987.

Loughran, Trish. “Disseminating Common Sense: Thomas Paine and the Problem of the Early National Bestseller.” American Literature 78.1 (March 2006): 1-28.

4 Comments on ‘Common Sense, by Thomas Paine (1776)’

Fascinating and well-written-thanks!

Happy Independence Day to Thomas Paine!

How interesting! Thanks, Megan.

Megan,

Can you possibly help me. Do you know the physical dimensions of the Jan 9, 1776 first edition of Common Sense. Also the total number of pages? Any help can give me will be most appreciated.

We don’t have the first edition, so I can’t help with specific information about that. But our third edition is about 19.5 cm (may have been trimmed slightly for binding), and the original Paine essay is 79 pages.