This article is more than 5 years old.

I WRITE the Wonders of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION, flying from the Depravations of Europe, to the American Strand: And, assisted by the Holy Author of that Religion, I do, with all Conscience of Truth, required therein by Him, who is the Truth it self, Report the Wonderful Displays of His Infinite Power, Wisdom, Goodness, and Faithfulness, wherewith His Divine Providence hath Irradiated an Indian Wilderness.

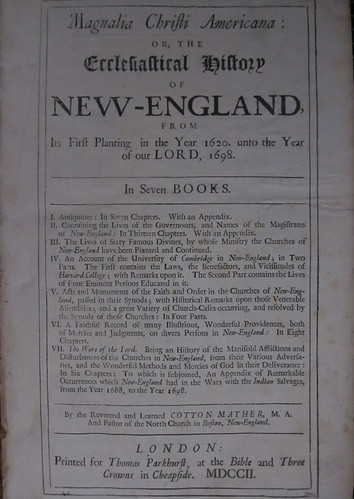

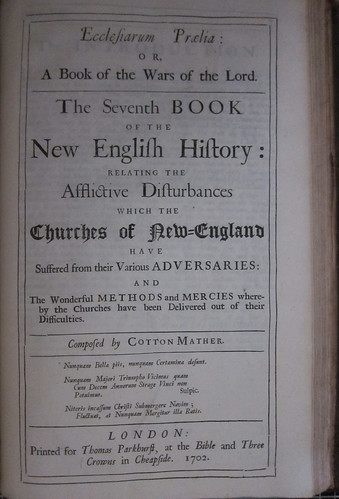

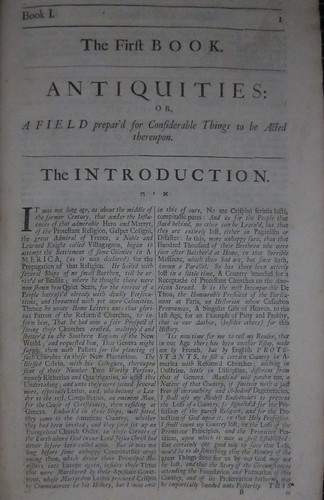

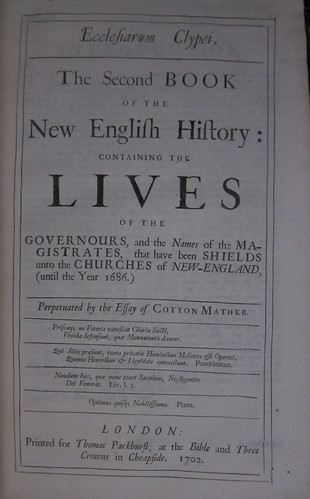

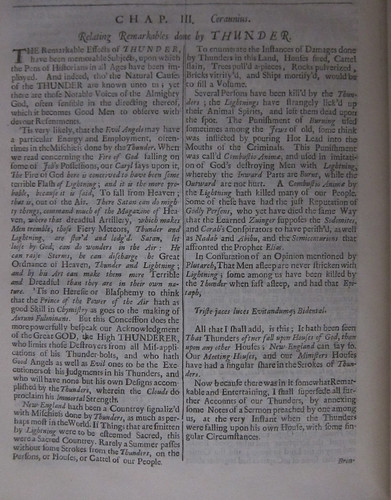

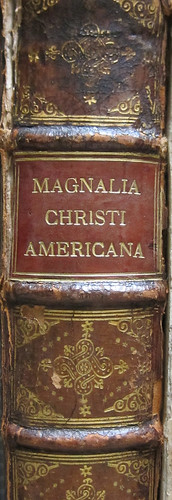

These opening lines of Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana set the tone for his epic and exhaustive account of 17th-century Puritan New England. Running to nearly 700 pages in printed form, the Magnalia includes biographical sketches of civic and religious leaders, a history of Harvard College, arguments over church polity and discipline, descriptions of the threats and hardships (Indian attacks, Roger Williams, witches, Anne Hutchinson) endured by the Puritan faithful, and many accounts of the signs and “wonders” experienced by the colonists as evidences of God’s direct intervention in human affairs. For Mather, human history was merely a manifestation of the epic struggle between God and the forces of evil. The Magnalia is, Michael P. Winship observes, “the last great document in the orthodox providential tradition” [74].

Cotton Mather (1663-1728) was the third generation of a dynasty of Puritan ministers in North America. His grandfathers, Richard Mather and John Cotton, were prominent ministers and founders of the New England colony. His father Increase Mather was also an important religious leader, minister of Boston’s Second Church, President of Harvard College, and the colony’s official envoy to the English monarchs James II and William and Mary. Cotton, the eldest son, was from a young age acutely conscious of the family expectations. After receiving degrees from Harvard and the University of Glasgow, Cotton Mather joined his father in ministry at Second Church in Boston.

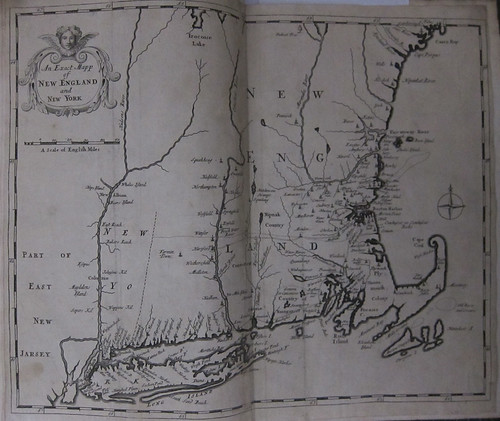

Map of New England included in the first edition of the Magnalia Christi Americana

Map of New England included in the first edition of the Magnalia Christi Americana

In 1693 Cotton Mather recorded in his diary that in July of that year he “formed a Design, to endeavour, THE CHURCH-HISTORY OF THIS COUNTREY.” Encouraged by his fellow-clergy, Mather says that he set himself “to cry mightily unto the Lord, that if my Undertaking herein might bee for His Glory, Hee would grant mee His Countenance and Assistance in it. (However, I did not actually begin this Work, till the latter End of the year.)” The young Rev. Mather worked on his “Church-History ” (as he always referred to it) for the next four years. Finally in August of 1697 he records in the diary a special thanksgiving for “the singular Favour of the Lord unto mee, in upholding, and assisting mee, to finish my CHURCH-HISTORY.”

Mather had published many sermons and small pamphlets with the local Boston printers. But a work the size of the Magnalia was beyond the capabilities of any printing operation in North America. If his manuscript was to be published, it would have to be sent to London. This was not a small undertaking. Since Mather likely had no extra copy of his lengthy manuscript, he did not want to send it across the ocean unaccompanied. It was not until June of 1700 that Mather recorded:

I this Day put up my Church-History, and pen down Directions about the publishing of it. It is a work of near 300 sheets; and has lain by me, diverse Years, for want of a fitt Opportunity to send it. A Gentleman, just now sailing for England, undertakes the care of it; and by his Hand I send it for London. O my Lord Jesus Christ, lett thy Good Angels accompany it!

The gentleman in question was Mather’s friend Edward Bromfield, who delivered the manuscript to Rev. John Quick, a Presbyterian minister and friend of Increase Mather. But London publishers were skeptical about the rather unwieldy manuscript. Mather worked himself into a state of great anxiety about it, but finally in June 1701 he heard from Bromfield that a sympathetic printer, Robert Hackshaw, had been found who was willing to finance the publication. In fact Hackshaw offloaded the printing, along with a large stock of inferior paper from his warehouse, onto another publisher, Thomas Parkhurst.

Mather finally saw a copy of his published work on 30 October 1702. He “sett apart this Day, for solemn THANKSGIVING unto God, for His watchful and gracious Providence over that Work.” But he could not help being somewhat disappointed in the final product. The folio volume was indifferently printed in two columns on cheap paper, and it was riddled with errors. Mather included an errata sheet in some of the copies sold in North America, but most copies remained uncorrected. Some of Mather’s critics took him to task for errors that were in fact the fault of his printer.

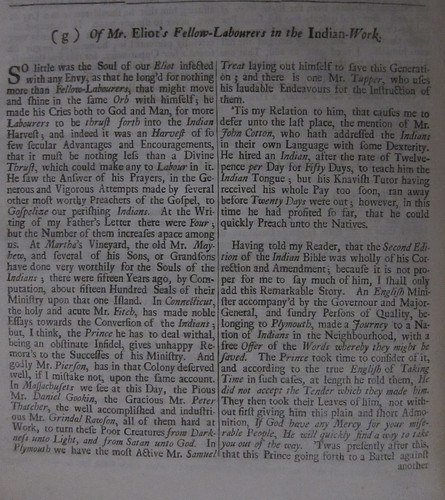

From Mather’s Life of John Eliot, a description of Eliot’s Indian missions and the second edition of his Algonquin Bible

From Mather’s Life of John Eliot, a description of Eliot’s Indian missions and the second edition of his Algonquin Bible

The Magnalia Christi Americana received a mixed reception on both sides of the Atlantic. Many readers praised it, but others thought the work was outdated in both style and substance before it was even published. And indeed, many of the “wonders” that Mather recounted as evidence of God’s providence would be explained away by the next generation as natural phenomena.

Mather’s style was not the “plain” Puritan idiom admired by future literary historians, but a very late Baroque style– wordy, ornamental, studded with metaphor and with classical and Biblical allusions. Many of his contemporaries accused him of being overly pedantic, and later readers tended to agree. Writing in the North American Review in 1818, William Tudor famously described the Magnalia as “a chaotick mass of history, biography, obsolete creeds, witchcraft, and Indian wars, interspersed with bad puns, and numerous quotations in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew which rise up like so many decayed, hideous stumps to arrest the eye and deform the surface.”

The Magnalia Christi Americana was not published again until 1820, when it appeared in its first American edition. American writers of the mid-19th century in particular had a love/hate relationship with the Magnalia. Hawthorne, Poe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and many others borrowed Mather’s source material as they formed a mythology of America’s origins. But they tended to see Mather as at best quaint and credulous, and at worst an example of all that was wrong with the Puritan forefathers– most notably the vanity, religious intolerance, and misogyny that led to the Salem witch trials debacle.

An unbiased reading of Mather’s work suggests that this is not quite fair. In the accounts of the Salem events in particular, Mather comes across in the Magnalia as a bit defensive but also genuinely conflicted.

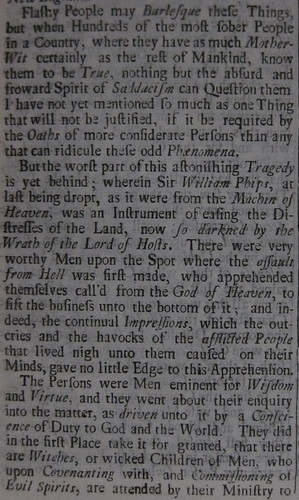

Excerpt from Mather’s Life of William Phips, describing the situation in Salem

Excerpt from Mather’s Life of William Phips, describing the situation in Salem

Mather was not unaware of the changing intellectual currents of his day. He had a keen interest in the new pursuit of natural science: he considered giving up the ministry to study medicine at one point, and he campaigned for controversial smallpox inoculation during an outbreak in Boston. But he remained firmly committed to the theological outlook of his grandfathers, the first generation of New England Puritans. This tension is evident in Mather’s sprawling, messy, flawed, but fascinating book. The Magnalia is, as Kenneth Murdock observes in his introduction to the 1977 scholarly edition, “a completely idiosyncratic document, one which none of Mather’s contemporaries could, or would, have written.”[46]

Wake Forest’s copy of the first edition was part of the library of Charles Babcock, which was donated to the University in the 1970s. It also bears the bookplate of Charles Bruce, (1682-1747). Viscount Bruce’s amassed a large personal library, the catalog of which was published in 1733, one of the first published catalogs of private libraries in Britain.

References

Bercovitch, Sacvan. “New England Epic: Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana”, ELH Vol. 33, No. 3 (Sep., 1966), pp. 337-350.

Mather, Cotton, and Kenneth Ballard Murdock. Magnalia Christi Americana: Books I and II. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1977.

Winship, Michael. Seers of God: Puritan Providentialism in the Restoration and Early Enlightenment. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

1 Comment on ‘Magnalia Christi Americana, by Cotton Mather (1702)’

So interesting, Megan! Thanks again for another great rare book of the month.