This article is more than 5 years old.

The Renaissance scholar Aldus Manutius (ca. 1451-1515) began his career in typical fashion, as a tutor to an aristocratic Roman family. We don’t know what prompted him in 1490 to move to Venice and try his hand at a business venture involving the exciting new technology that was spreading across Europe: printing with moveable type. But over the next 25 years Aldus became the most important scholar/printer of the Italian Renaissance.

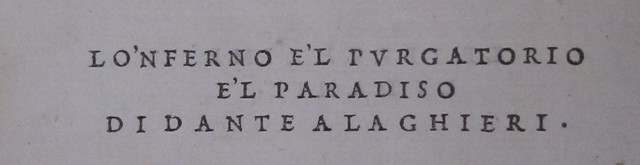

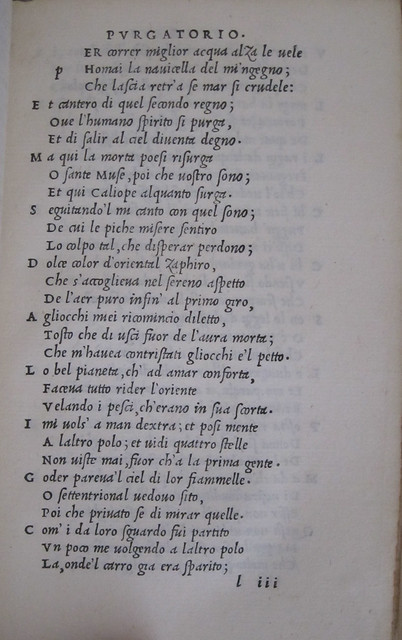

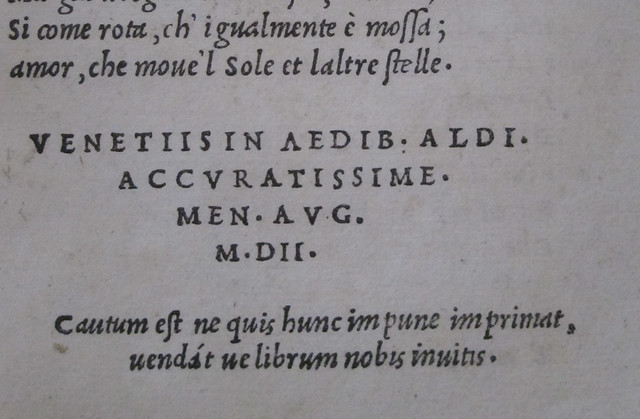

The Aldine Press, as it became known, began by printing editions of Latin and Greek classics that were in demand by scholars. But Aldus also published works in the Italian vernacular, and in 1502 he undertook an edition of the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri (1265-1321).

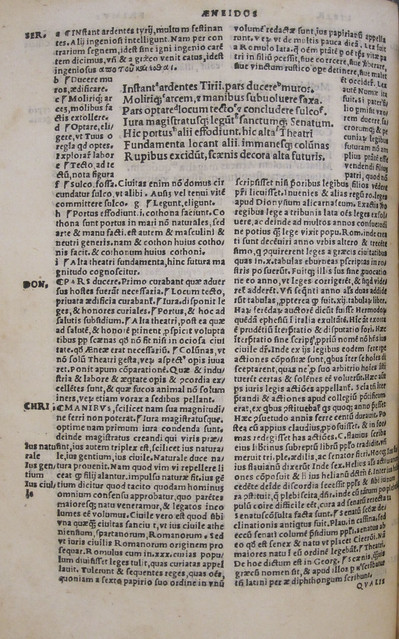

Dante wrote his epic poem between 1308 and 1321. There are no surviving manuscripts in Dante’s own hand, but the work was widely copied and over 400 manuscript copies from the 14th century are known to exist. Dante’s popularity continued unabated into the 15th century, and several Italian printers issued editions of the Divine Comedy between 1472 and 1500. Most of these early editions included the extensive commentary by Florentine scholar Cristoforo Landino. In many of them the commentary almost overwhelmed the text, and little attention was given to accurate editing of the poem itself.

In this page from a 15th century edition of Vergil’s works, seven lines of text from the Aeneid are surrounded by extensive commentary. The Dante editions with Landino commentary would have looked similar.

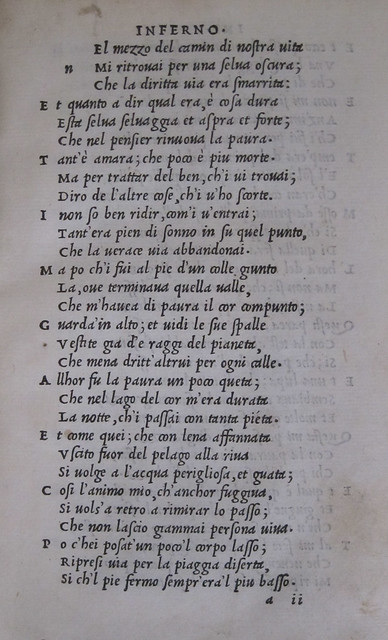

Aldus’s edition, by contrast, dispensed with all commentary and presented the unadorned text of the poem in a small octavo format.

The text itself was a new version edited by Aldus’s friend and frequent collaborator, Pietro Bembo. Its origin was an early manuscript version of the Divine Comedy from the library of Bembo’s father (though it was not, as Bembo claimed, in Dante’s own hand).

Bembo was a Renaissance humanist and an accomplished scholar. Rather than writing a lengthy gloss on the poem, as Landino had done, he concentrated on making the text itself understandable for his 16th century Italian readers. After the publication of Aldus’s 1502 edition, Bembo’s version became the standard Dante text until well into the 19th century.

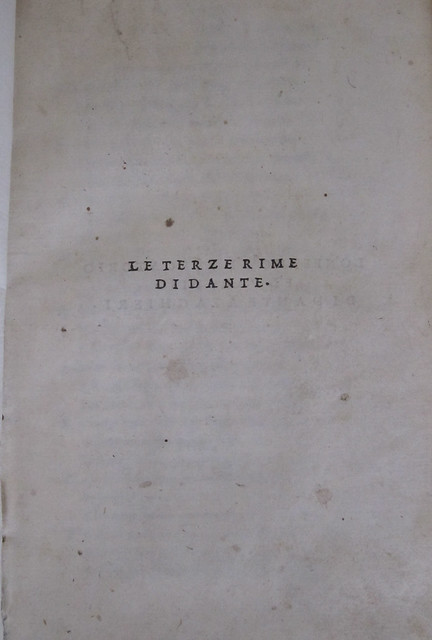

One of Aldus’s and Bembo’s major innovations was the liberal use of punctuation, a feature often missing from manuscripts and earlier printed texts.

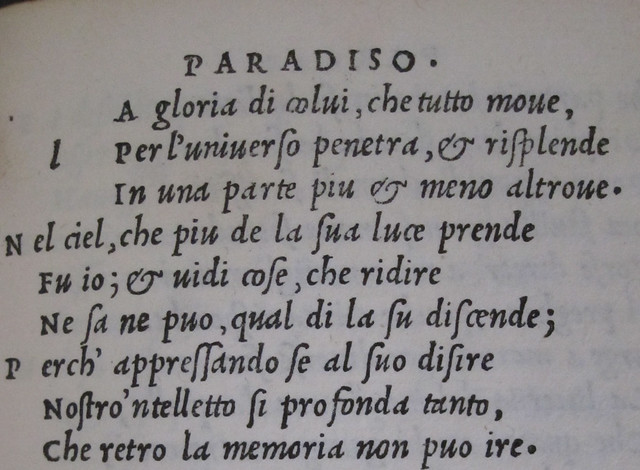

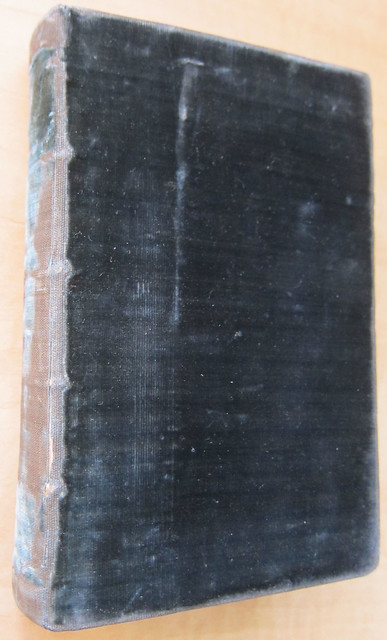

The Aldine Press Dante was typical of many of Aldus’s imprints in that it was a small octavo volume, affordable and easily portable. Many 15th century editions of the classics were large folio volumes, impressive but unwieldy and extremely expensive, with text often buried under centuries of accumulated notes. Aldus realized that there was a market in the scholarly community for well-edited and reasonably priced texts. His Dante is one of many small volumes, printed in his trademark italic font. Aldus was an innovator in typeface design, and his italic type was based on the handwriting of two highly accomplished Italian scribes.

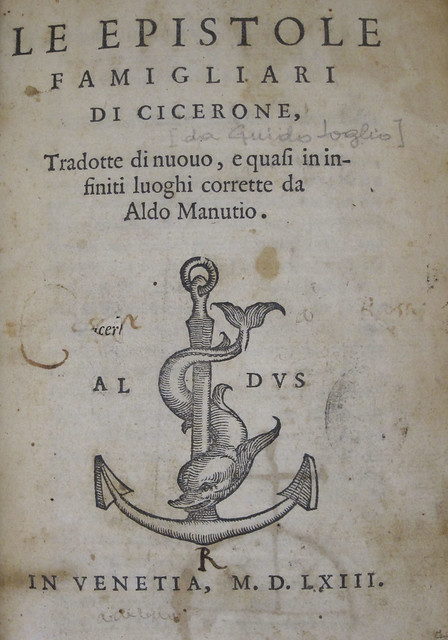

The 1502 Divine Comedy was the first book in which Aldus Manutius used his famous dolphin and anchor printer’s device. The emblem was taken from a Roman medal given to Aldus by Pietro Bembo. The swift dolphin and the immovable anchor are a visual representation of the motto “festina lente” or “make haste slowly.” This quote from Emperor Augustus was an appropriate motto for Aldus, whose painstaking scholarship and editing underpinned his prolific output as a printer.

However, not all copies of the 1502 Dante have the Aldine device. The engraved illustration was apparently not ready when the first copies of the Divine Comedy went to press, so the earliest issues (of which ZSR’s copy is one) do not have the device.

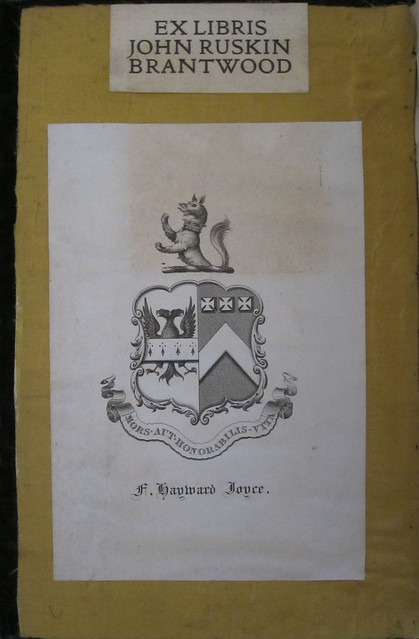

ZSR Library’s copy of the Aldine Press Divina Commedia contains bookplates from three former owners. One of these was famous in his own right: the Victorian artist and critic John Ruskin (1823-1900).

Ruskin was one of the most influential writers on art and society in 19th century England, and he was a great admirer of Dante. In his Stones of Venice Ruskin wrote

I think that the central man of all the world, as representing in perfect balance the imaginative, moral, and intellectual faculties, all at their highest, is Dante.

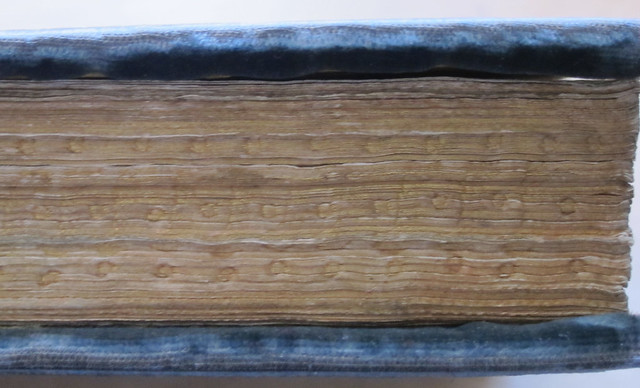

Ruskin made his first visit to Italy in 1845, spending time in Venice and Florence. It is possible that he acquired the Aldine Press volume during this trip. It is also possible that Ruskin was responsible for having the volume rebound in blue velvet, with yellow silk endpapers and gauffred edges.

In any case, it is clear that this copy of the Aldine Press Dante has been a treasured possession of many owners over the past 500 years. ZSR Library purchased the book from bookseller William Salloch in 1986. All of the images above are from volumes in the ZSR Rare Books Collection.

3 Comments on ‘Divina Commedia, by Dante Alighieri (Aldine Press, 1502)’

Wonderful synopsis of early printing: Aldus & Bembo. I had to read the definition of gauffred and look at the image to really understand it. Thanks for a great piece.

Wonderful! I love the small text and the overwhelming commentary. I also think my new personal motto will be “make haste slowly.” Thanks for writing this up, Megan.

Megan, many thanks for your wonderful and very informative article on Dante and early Italian printing.

I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Charles