This article is more than 5 years old.

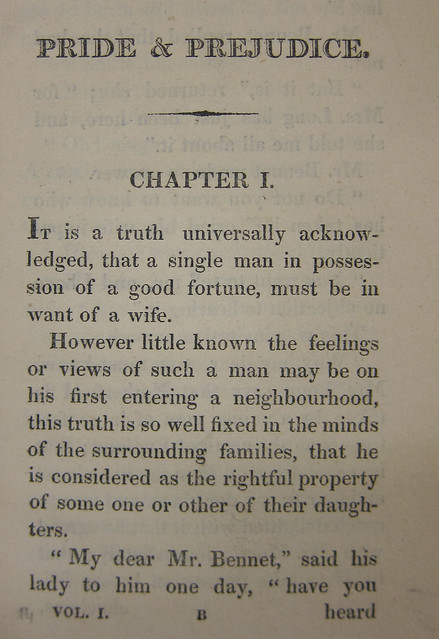

On 29 January 1813 Jane Austen (1775-1817) wrote to her sister Cassandra with exciting news: “I want to tell you that I have got my own darling child from London.” The “darling child” was a copy of her newly published book Pride and Prejudice.

On this the 200th anniversary of its publication Pride and Prejudice is an undisputed literary classic, as popular with readers today as it was in 1813. But the novel’s path to publication was a long one.

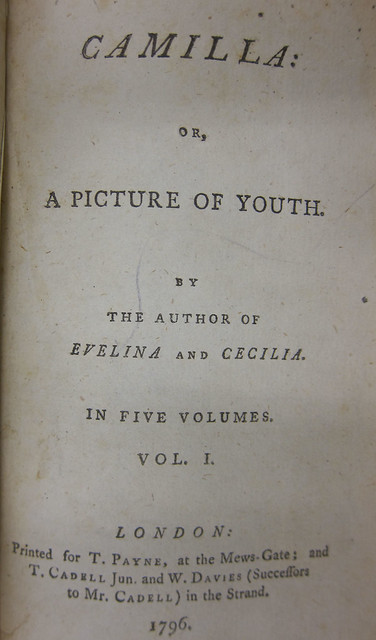

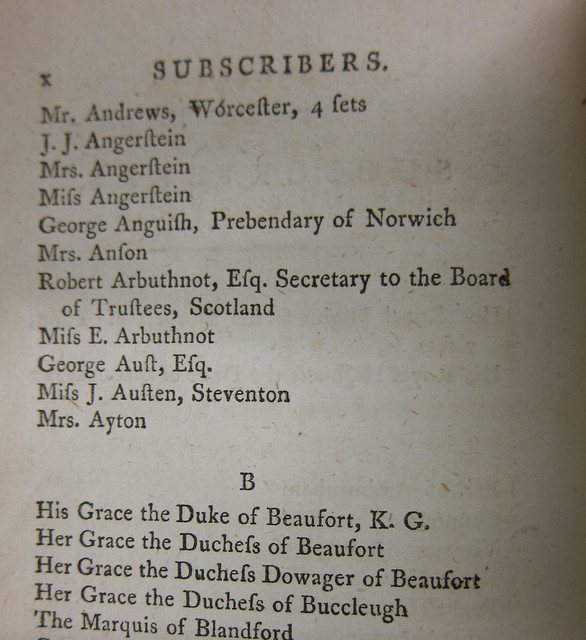

Jane Austen began writing novels while still a teenager. The second youngest of seven children, Austen had the good fortune to be born into a family of literary enthusiasts. Her parents, brothers, and sister all had a lively interest in the popular books of the day, and they encouraged Jane’s literary efforts. Like the rest of her family, Jane was an avid reader. A favorite author was Frances Burney, one of the most popular and successful novelists of the late 18th century. That Jane Austen was a devoted fan is evident from the fact that she is listed as a subscriber in Burney’s 1795 novel Camilla.

She appears in the subscriber list as “Miss J. Austen, Steventon.” It was the only time that Jane Austen’s name appeared in print during her lifetime.

The novel that would become Pride and Prejudice was probably written in 1796 and originally titled First Impressions. Jane’s father thought highly enough of his 22-year-old daughter’s work that he wrote to Fanny Burney’s publisher to inquire whether he would be interested in “a Manuscript Novel, comprised in three Vols. About the length of Miss Burney’s Evelina.”

The publisher, Thomas Cadell, Jr., declined even to read the manuscript.

Meanwhile, Jane kept writing. Her novels and stories were circulated in manuscript among friends and family. And in 1803 she sold a novel called Susan to the publisher Benjamin Crosby for £10. For this sum Austen relinquished all copyright to Crosby, who was then free to do with the manuscript as he wished. And what he did was nothing. The book remained unpublished, much to Austen’s frustration. She eventually had to purchase the manuscript back from the publisher. It was published as Northanger Abbey after her death.

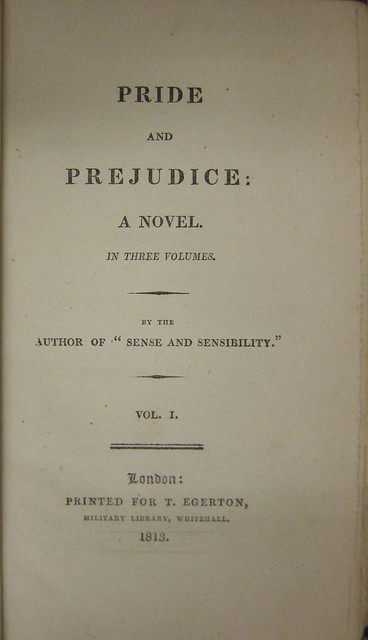

Austen had better luck with a novel called Sense and Sensibility. In 1810 the publisher Thomas Egerton accepted the book on commission. Egerton would finance the publication and receive 10% of all profits from the sales, but Austen would be responsible for repaying any losses should the book prove a failure. Fortunately for her, it was not a failure. Sense and Sensibility: A Novel in Three Volumes, appeared in 1811 and proved quite popular with readers. As was common with novels of the 18th and early 19th century, the author was not identified by name. The title page only allowed that the book was written “By a Lady.”

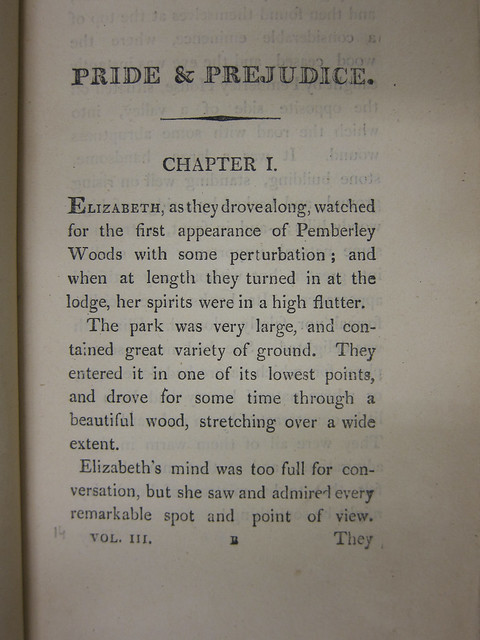

When Austen offered the revised manuscript of First Impressions, now called Pride and Prejudice (the new title was likely a reference to the ending of Frances Burney’s Cecilia), Egerton purchased the copyright for £110. It was hurried into print and was available for sale in London by January 1813.

In her January 29 letter to Cassandra, Jane seems quite pleased with the book:

I must confess that I think [Elizabeth Bennet] as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, and how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least I do not know. There are a few typical errors; and a ” said he,” or a “said she,” would sometimes make the dialogue more immediately clear; but I do not write for such dull elves as have not a great deal of ingenuity themselves.

Austen’s contemporary readers agreed with her assessment that Pride and Prejudice was better than the average work of popular fiction. The Critical Review published a favorable account of the novel in March 1813, praising in particular Austen’s skill at characterization.

Elizabeth’s sense and conduct are of a superior order to those of the common heroines of novels. For her independence of character, which is kept within the proper line of decorum, and her well-timed sprightliness, she teaches the man of Family-Pride to know himself.

The Critical Review also approved of the lessons that young, female readers were likely to take away from Pride and Prejudice. Lydia’s story, for example, showed “the folly of letting young girls have their own way” and the danger of consorting with military officers. And the line that the author “draws. . . between the prudent and the mercenary in matrimonial concerns” was deemed potentially “useful to our fair readers.” The reviewer concluded with the assertion that

[T]his performance. . . rises very superior to any novel we have lately met with in the delineation of domestic scenes. Nor is there one character which appears flat, or obtrudes itself upon the notice of the reader with troublesome impertinence. There is not one person in the drama with whom we could readily dispense;– they all have their proper places; and fill their several stations, with great credit to themselves, and much satisfaction to the reader.

William Gifford, editor of the Quarterly Review, echoed the general sentiment that Pride and Prejudice was an improvement over the many overblown and sensational novels of the day:

I have for the first time looked into ‘Pride and Prejudice’; and it is really a very pretty thing. No dark passages; no secret chambers; no wind-howlings in long galleries; no drops of blood upon a rusty dagger– things that should now be left to ladies’ maids and sentimental washerwomen.” [Gilson 27]

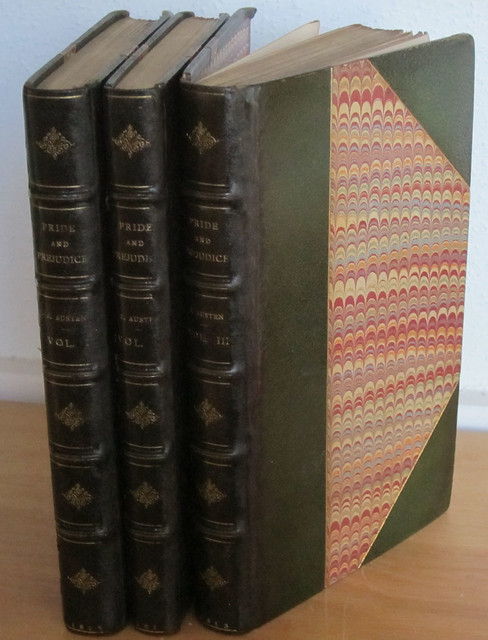

The first printing of Pride and Prejudice likely consisted of about 1000-1200 copies– a typical first run for a novel at that time. And like most novels, it was published in a small duodecimo format (the large printed sheet folded to form twelve pages) in three volumes.

The three-volume novel was becoming the standard form for popular fiction in the early 19th century. Even for books like Pride and Prejudice that were not so long as to be unwieldy in one volume, multiple volumes were the preferred format. This was largely due to the demands of private circulating libraries, which were by 1800 the largest purchaser of works of fiction.

English circulating libraries had their beginnings in the late 17th century, when some booksellers hit on the idea of offering books for rent as well as for sale. By the mid-18th century private lending libraries were a widespread phenomenon. After paying an annual subscription fee, a member was entitled to borrow books from the library’s collection. Most libraries had a sliding scale for fees: a higher subscription rate allowed one to borrow more books at one time. For such libraries the advantage of multi-volume works was that more than one borrower could have access to the book simultaneously, each reading one volume and returning it for the next.

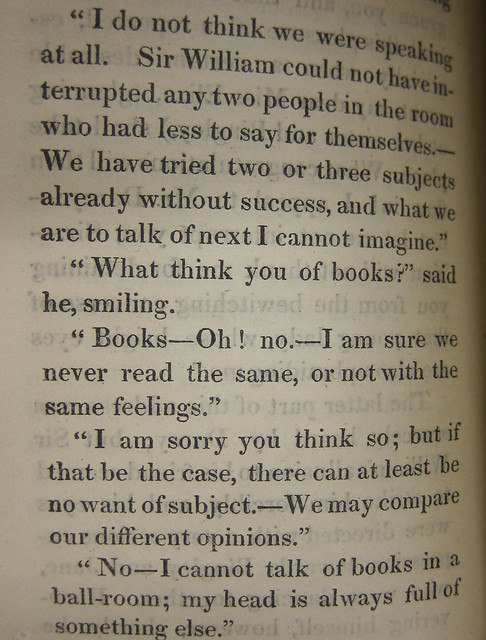

Jane Austen herself was an enthusiastic patron of various circulating libraries. Books, reading, and libraries figure constantly in her novels and her letters.

Pride and Prejudice proved even more popular with readers than Sense and Sensibility. Anne Isabella Milbanke (soon to be Lady Byron) wrote to her mother early in 1813 that Pride and Prejudice was “at present the fashionable novel” among the well-to-do at the London social season. There was much speculation about the book’s authorship. In May Milbanke wrote that “I have finished the Novel called Pride and Prejudice, which I think a very superior work . . . . I wish much to know who is the author or ess as I am told.” [Gilson 25].

Although Jane Austen’s name did not appear on the title pages of any of her novels during her lifetime, the popularity of Pride and Prejudice in the small world of the English leisure classes ensured that her identity was soon widely known. Writing to her brother Frank in September 1813 Austen noted that

The truth is that the Secret has spread so far as to be scarcely the Shadow of a secret now — & that I believe whenever the 3d appears, I shall not even attempt to tell Lies about it.– I shall rather try to make all the Money than all the Mystery I can of it.

As an unmarried woman in her thirties with no inheritance, Jane Austen had good reason to hope that her books would make money. She was otherwise entirely dependent on her brothers’ charity. Pride and Prejudice was successful enough that a second edition was printed in October 1813, and her third novel, Mansfield Park, was published the next year.

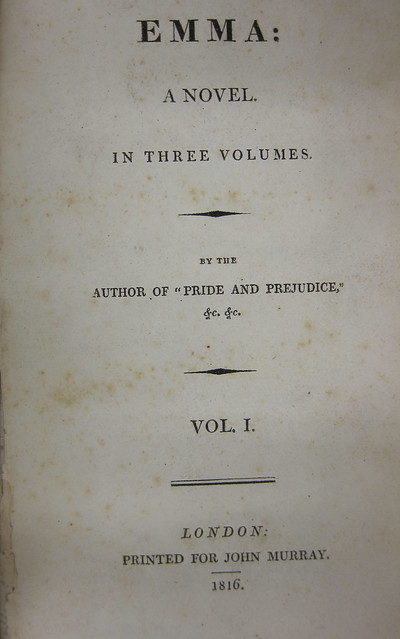

By the time Emma was ready for publication in 1816, Jane Austen had become famous enough that the Prince Regent requested that she dedicate it to him . Austen was no great admirer of the profligate Prince, but she complied. She had also acquired a more prestigious publisher, John Murray, who published the book for a ten percent commission.

Jane Austen did not live to see her last two novels (Persuasion and Northanger Abbey) in print. She died in 1817 at the age of 42.

Interest in her books, however, shows no sign of waning nearly 200 years later. Pride and Prejudice has not been out of print since the 19th century and has been subjected to stage, television, and film adaptations, sequels, prequels, fan fiction, and permutations that Jane Austen could hardly have imagined. But readers who find their way back to the original will likely agree with Sir Walter Scott that “That young lady had a talent for describing the involvements, feelings, and characters of ordinary life, which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with” [Gilson 475].

ZSR Library received the first edition of Pride and Prejudice as part of the library of Charles Babcock. The volume also has the bookplate of another former owner, Robert Hoe, a 19th century book collector and manufacturer of printing machinery who was the first president of the Grolier Club.

Recommended reading

Bautz, Annika. The Reception of Jane Austen and Walter Scott. London: Continuum, 2007.

Erickson, Lee. “The Economy of Novel Reading: Jane Austen and the Circulating Library.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 . 30. 4 (Autumn, 1990): 573-590. JSTOR http://www.jstor.org/stable/450560 .

8 Comments on ‘Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen (1813)’

Megan – Excellent description of Austen, her times and printed works.

I always learn so much from your essays!

Lovely history, Megan!

Wonderful summary of a favorite book (and movie, and permutation)!

I love all things Jane Austen and “Pride and Prejudice” is my favorite of her novels. Thanks for giving us this behind the scenes look at its publication, (and artfully working in “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies”.)

Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility was the final Jeopardy question in tonight’s show! I wowed Ron with my vast knowledge. Thank you for the perfect timing on this today 🙂 (Final answer under the category of Women Authors: Jane Austen’s first published title was the last in the alphabet of her titles (I’m paraphrasing here))

Extremely well done, Megan. Thank you.

I’ll have to stop by and see this book. Loved the blog.