This article is more than 5 years old.

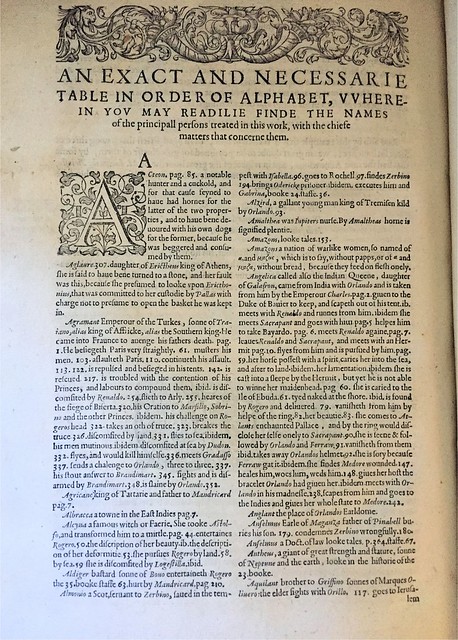

The Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto’s epic Orlando Furioso first appeared in print exactly 500 years ago. Taking inspiration from the French Chanson de Roland, Ariosto recounted the fantastic adventures of one of Charlemagne’s knights, Roland (Orlando) and his associates. The main stories concern Orlando, who has been driven mad by his unrequited love for the lady Angelica; and the Christian warrior maiden Bradamante, who falls in love with the Muslim hero Ruggiero. Many other subplots and supporting characters fill the pages, making this one of the longest poems of the Renaissance.

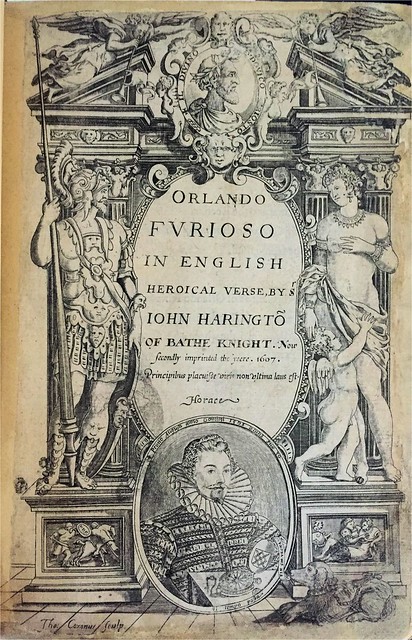

Orlando Furioso was also one of the most popular literary works in 16th century Europe. After its first printing in 1516, hundreds of later editions appeared, many of them profusely illustrated. The work was already well known in England in its original Italian and in a French translation when Sir John Harington (1561-1612) published the first full English translation in 1591. In 1607 Harington put out a new edition, with various revisions and additions. ZSR Special Collections recently acquired a copy of this 1607 second edition.

When he began his translation around 1583, Harington was a well-connected young courtier. His family had ties to the Tudors, and Queen Elizabeth herself was his godmother. Legend has it that Harington first translated a racy bit of the Furioso which was circulated in manuscript among Elizabeth’s ladies-in-waiting. The Queen disapproved, and as punishment she banished Harington to his country estate in Somerset to translate Ariosto’s nearly 40,000-line poem in its entirety.

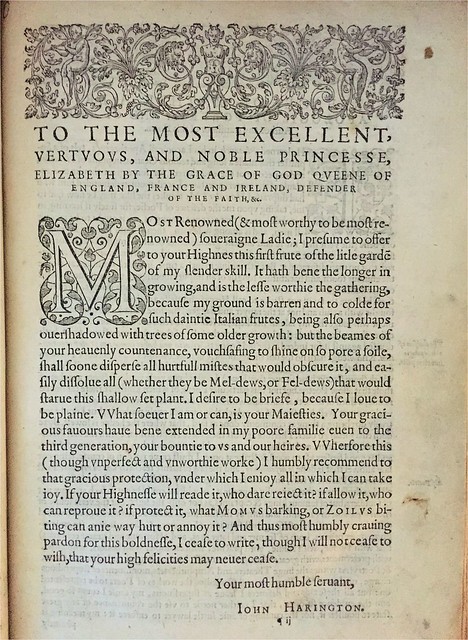

Whether or not this origin story is entirely accurate, Harington did dedicate the finished translation to his royal godmother.

Harington’s translation was generally well received by his contemporaries (although Ben Jonson, predictably, hated it). Like most Renaissance translators, Harington had no qualms about making minor changes to the original text to make it more accessible to English readers. And the many paratextual elements of Harington’s book provide clues to how English readers interacted with Italian authors and texts during the 16th century. As one modern critic observed

Harington’s translation provides a fascinating illustration of Elizabethan “Englishing” of the Furioso. Harington compresses and revises Ariosto’s lines whenever it suits him, and he expands several episodes when he deems it necessary. Harington also comments extensively on Ariosto’s text: in addition to a substantial Preface and Apology, he supplied marginal notes throughout the poem and concludes each canto with a Morall, a Historie, an Allegorie, and often an Allusion as well. Many of these commentaries point to those aspects of Ariosto’s poem that were of particular interest or concern to the Elizabethans, or that were most likely to trouble them in some way, for these tend to be the very points that Harington explicates most painfully. (Miranda Johnson-Haddad, “Englishing Ariosto: “Orlando Furioso” at the Court of Elizabeth I”. Comparative Literature Studies 31.4 (1994): 323–350.)

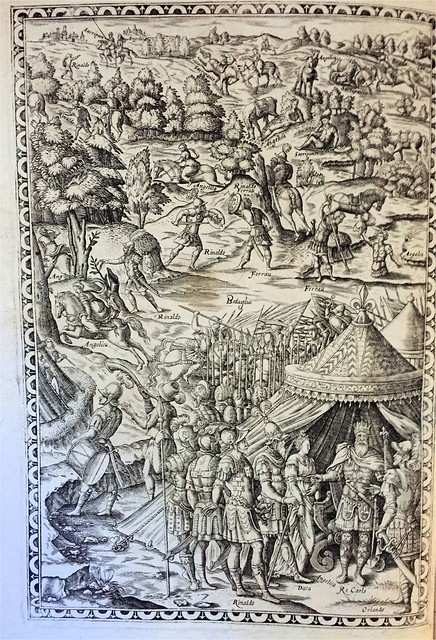

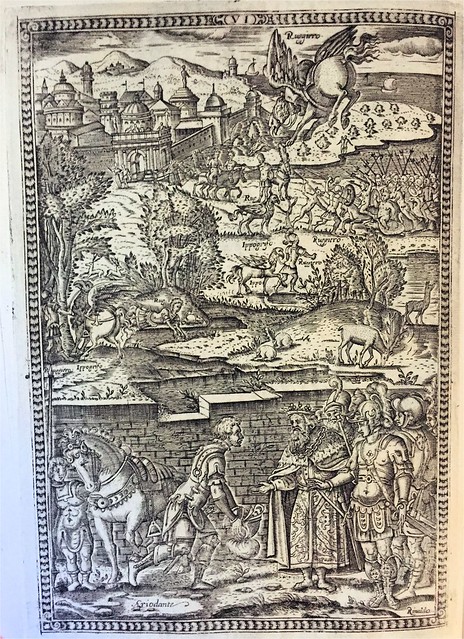

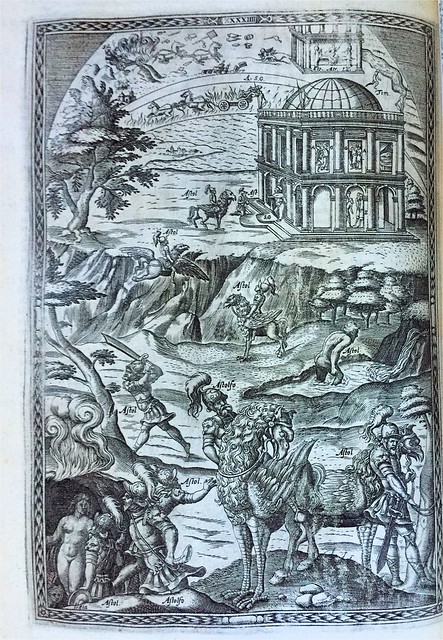

Harington’s Orlando Furioso is also notable for its many engraved illustrations. These were modeled after the famous 1584 Italian edition published by Francesco di Franceschi. Harington was especially proud of these engravings and described them in detail in his Preface:

As for the pictures, they are all cut in brasse, and most of them by the best workemen in that kinde, that have bene in this land this manie yeares: yet I will not praise them too much, because I gave direction for their making, and in regard tehreof, I may be thought paritall, but this I may truly say, that (for mine owne part) I have not seene anie made in England better. . . .

The use of the picture is evident, which is, that (having read over the booke) you may read it (as it were againe) in the very picture, and one thing is to be noted, which every one (haply) will not observe, namely the perspective in every figure. For the personages of men,the shapes of horses, and such like, are made large at the bottome, and lesser upward, asif you were to behold all the same in a plaine, that which is nearest seemes greatest, and the fardest, shewes smallest, which is the chief art in picture.

Harington’s biographer comments that “The achievement of the illustrations may be compared to the translation itself: much is lost in terms of subtlety and variety; yet a bold outline of the original is conveyed, certain narrative aspects are robustly underlined, and the whole bears the stamp of Harington’s irrepressibly individual artistic personality.” (D. H. Craig, Sir John Harington (Boston, G. K. Hall, 1985), 45.)

Orlando Furioso was the high point of Harington’s literary career, and his text remained the only complete English translation until the mid-18th century. He published several other minor works and managed, more or less, to stay in the good graces of the royal family.

Harington is probably best known today for inventing the flush toilet and for being an ancestor of a popular Game of Thrones actor— making him a Renaissance man in every sense of the word.