This article is more than 5 years old.

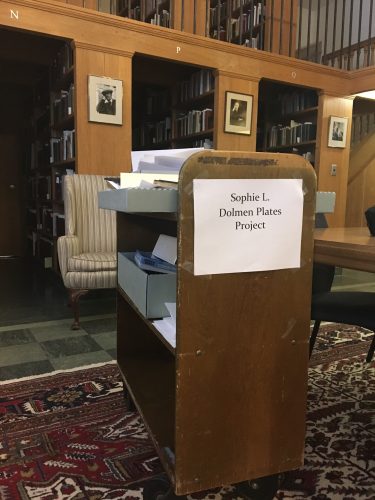

The Dolmen Press was an Irish publishing house active from 1951-1987, founded and run by Liam Miller and his wife, Josephine Miller. The Z. Smith Reynolds Library at Wake Forest University acquired the Dolmen’s design work, printing plates, correspondence and administrative papers in the late 1980s. This is a treasure trove of Irish poetry, the art of many famous artists, and a mesmerizing shrine to the work of W.B. Yeats. When I encountered the collection, the printing plates for the Dolmen publications were in about fifteen laden boxes.

ZSR Preservation Librarian Craig Fansler wanted to create a directory of images so that the library had a handy guide to see the vast collection of art. My motives were less pure. I wanted to touch the plates. You see, I am the kind of person that museums put up glass cases up to prevent from touching precious objects. To get to feel the metal, linoleum, or wooden hand- carved plates, I would do whatever was needed. The library already had a collection of the scans of the plates themselves. But, since printing plates are in inverse for printing, the images are often hard to make sense of and truly appreciate. It seemed exciting to print each plate and see what the image was.

When we started our first box, it was all Tate Adams from his book Soul Cages. That was straight forward because everything in the box was by the same artist and published in the same book. But, then things got tricky. The next box had artists with the last letter “B,” but also, lots of plates that were of unknown artists and publications. Eventually, the loose alphabetical order gave way completely. Six boxes in, where I should have been mid alphabet, I was finding more Mia Cranwill plates and Bridget Swinton work, in addition to a lot of unlabeled chaos. Craig and I realized two things. First, that when the original finding aid was created long ago, some plates had been omitted, so we did not know how many plates there were in total. And second, this project had just became much bigger than we had expected.

This was my first processing project ever and the parameters were unknown. We had to bring in back up; our collections archivist Stephanie Bennett whipped us into shape quickly. She became our organization guru. With her help, we established what information about each plate I would record.

- The material of each plate

- The image depicted

- The artist (if known)

- The publication it is in (if known)

- Any notes from the back of the plate

- Call number of the publication if we had it

Then I numbered each plate and its print. Finally, I took a picture of the print and went back later to change photo resolution and link up photos to the excel sheet. Each box has it’s own numbering system. After about 500 plates, I got into a rhythm.

When the glare of the computer screen got tiresome, unpacking boxes kept me engaged. I loved the feel of the wooden plates the best because they are warm as opposed to the more numerous unmounted metal plates which are cold and thin. Craig’s immense knowledge of the collection allowed him to hunt down images in their publications so we could cite them. The Dolmen XXV: A Bibliography 1951-1976 by Liam Miller helped us tremendously. The detective work balanced out the monotony. Personally, getting to hold the work of Tate Adams, Pauline Bewick, Leonard Baskin, Louis le Brocquy, Juanita Casey, and the like, felt intimate and precious.

After eight months and over 1,200 plates we felt accomplished that we had further organized the plates into 37 boxes so that each was easier to lift and less dense to sort through. But after processing, I delved into metadata standardization aka madness. In my next post, I will discuss how I learned to standardize data, the options we considered for digital platforms, and some things I wish I had considered more carefully.

2 Comments on ‘Dolmen Printing Plates Processing Adventure: Part 1’

I love that you are documenting your biggest fellow project from the past year! It was a very valuable one for making the collection more accessible. Thanks for your work on this!

Sophie,

We created a very useful guide to Dolmen artists and their images.

Thanks so much for your help and dedication with this project, which will have lasting usefulness. Plus, we had fun! Good luck in Ireland.