This article is more than 5 years old.

For my final post in this three–part series about the Dolmen Collection Printing Plates processing project, I want to share some observations about the collection.

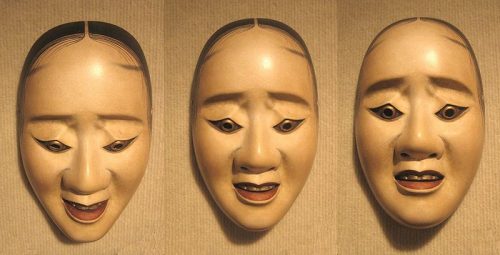

First of all, why does this collection matter? To answer this for myself, I thought about the most unique thing I had seen over the course of the project. The book Yeats and the Noh details the Irish Poet William Butler Yeats’s attempt to bring the themes of traditional Japanese Noh theater to the Irish stage. The plates from this book were jarring to me since images of Japanese masks clashed with what had become a steady stream of Christian imagery and Irish landscapes.

What did the Irish darling Yeats want with Japanese masks? (For a really great analysis, of Yeats’s connection to Noh theater, this jounral article is the one to read) I tried to make sense of it myself by requesting the book from our Special Collections. I read about how, for Yeats, “the secret of Noh lay in its stylization, its unity of images, and in its concentratedness” (130). From my western perspective, the masks were sort of scary and I realized that viewers in 1960s Ireland probably had the same sense of confusion I did. I see why Yeats pursued giving an audience that complex mixture of confusion, fear, and curiosity. It forces the audience to consider the other culture and our feelings regarding difference.

The Dolmen Press Collection is a form of material culture where we can study to see the overlap between poetry, Irish values, publishing, and sometimes, as in the case between Yeats and the Noh, interaction with other cultures. As I deleted extra spaces in my spreadsheet, I had a thought; archival processing is an act of homage. For the ZSR specifically, we have a collection from a different culture and a responsibility to make it accessible (all plates accounted for) and usable (able to be studied without damage done to the irreplaceable object).

Now that the collection has been processed, I hope that researchers use the collection. Avenues for future study could be the gender breakdown I found; 14 women artists versus 50 male artists. The female artists have 224 plates cumulatively. That means women account for only 18% of the collection. And male artists are attributed to 375 plates or about 30% of the collection. This means that for the majority of the plates, we don’t know who the artist was or where the image was published. However, it is interesting to observe that the difference between the amount of plates produced by men versus women is only by about 151 plates.

For these 600 plates that we couldn’t fully link to an artist or a publication, 463 of these are of unknown artist and title it is published in. We had about 49 plates that we did not print because they were fragile. Our hunch is that the Dolmen had many plates that were made, but never printed. For 144 of those images, we could find the publication it is printed in but not the artist who made it. For example, we have 21 images from the book “From Blake to ‘A Vision,’” by Kathleen Raine (New Yeats Papers XVII) that we are unsure of the artist, but have confirmed they are in the book. Or we have 37 images from “The History and Topography of Ireland” by Giraldus Cambrensis and John J. O’Meara that, again, we know are in the book, but we could not figure out who the artist is. These images could be attributed to an artist with more time and closer study of the Dolmen publications.

In terms of subjects depicted, I found two interesting threads that may provide fuel for another research project. First, overt Christian imagery was very common. Lots of the Dolmen published works were religious stories. Second, depictions of women were mostly in a religious context, part of a decorative motif, or as a witch/monster.

Of the 464 plates that we do not know anything about, there were 83 depictions of women, 13 of which were either Mary with baby Jesus, or Eve with Adam, or a woman kneeling next to a man. Interestingly, 40 figures were genderless, or extremely ambiguous. Of the 144 plates that we know the publication but not the artist, there are only 13 featuring women and two of those involve bestiality. Only 7 of these are religious in theme.

Although the processing labor involved a lot of difficulties, I enjoyed taking the time to make observations about themes that I saw while I worked. I now have a very great appreciation for processing requirements. After all, if materials cannot be found, they cannot be used, studied, or enjoyed. We process to protect. Despite the tough learning curves, I would do it again, and luckily, after I get my degree, I probably will.

1 Comment on ‘Dolmen Printing Plates Processing Adventure: Part 3’

Thanks for sharing your experience with Dolmen, Sophie!