This article is more than 5 years old.

On this day 200 years ago the third child of an estate manager was born in rural Warwickshire, England and christened Mary Anne Evans. We know her better as George Eliot, the nom de plume she adopted when she began to publish works of fiction in her late 30s. As George Eliot, she changed the landscape of 19th century literature, illuminating the inner lives of her characters as their moral decisions drove her stories, and transforming the novel into a genre that demanded respect from the literary establishment.

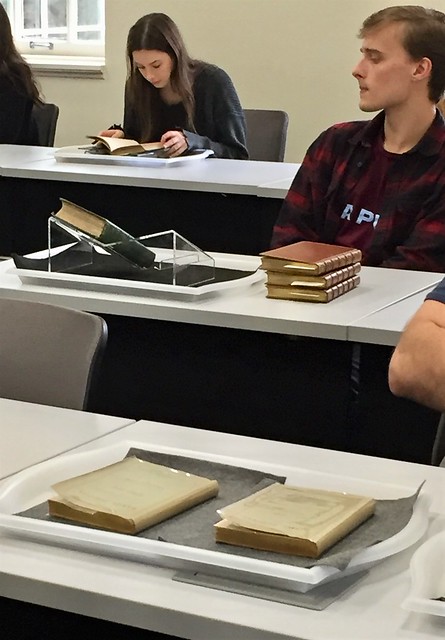

ZSR Special Collections and Archives has recently added several important works to our Eliot collection, thanks to a generous donation of funds by WFU alumni Dr. Richard Newsome and his wife Jerome, in honor of Professor of English and Provost emeritus Edwin G. Wilson. These recent acquisitions include a first editions of Scenes of Clerical Life, Silas Marner, Middlemarch, and Daniel Deronda.

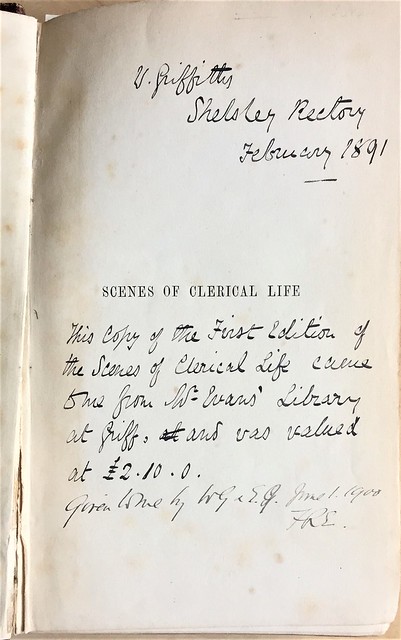

Scenes of Clerical Life was the first book published under the pseudonym George Eliot, although Marian (her preferred spelling in adulthood) Evans had published nonfiction essays and translations under her own name. This particular copy of Scenes of Clerical Life was originally owned by the author’s brother, Isaac Evans.

Marian Evans had a conventional upbringing, leaving school at age 16 to keep house for her widowed father. Her intellectual gifts showed themselves early and were encouraged by her doting father, and she had a close relationship with her older brother, Isaac. However, her family were less than happy when she became a freethinker and abandoned organized religion as a young woman.

An even more serious rift came in 1854 when Evans began a 25-year relationship with author George Henry Lewes. Lewes was technically married– his wife had left him for another man, but Victorian divorce laws prevented their legal separation. When Marian moved in with Lewes, Isaac immediately disowned her and refused all communication until after Lewes’s death.

Encouraged by Lewes, she began to write and publish fiction in her late 30s. Scenes of Clerical Life is her first published work of fiction and It brings together three short stories based on her rural childhood.

This copy was presumably a gift from the author to her brother, but did Isaac actually read it? We have no way of knowing. The inscription and annotations are by his son-in-law, Rev. William Griffith, who identifies several Warwickshire names and places that were presumably the models for Eliot’s fiction.

Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe, one of Eliot’s shorter novels, was for decades a mainstay of secondary school reading lists. This first edition was sent by Sir Godfrey Lushington, a civil servant in the British Home Office and a supporter of labor movements and prison reform, to an American friend, Mr. Lord, in April 1861. In a letter tipped in at the beginning of the volume, Sir Godfrey recommends the novel to the entire Lord family. He also references the coming civil war:

You and your family I trust are well— Would that I could say the same for your country, which seems to be on the eve of terrible disaster. It will be worth paying a good price to get rid of slavery.

George Eliot too would have been well aware of the brewing conflict in America. She was an admirer of Harriet Beecher Stowe (the two authors had extensive correspondence ), and the impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin inspired Eliot to write fiction that addressed current social issues.

Middlemarch, Eliot’s sixth published novel, is considered by many to be her greatest work. Her interconnected stories of the residents of a provincial English town outgrew the bounds of the traditional Victorian three-decker novel and were published in four volumes after their serial publication.

This copy is from the library of Richard Monckton Milnes, First Baron Houghton, a poet and literary patron and a close friend of George Eliot. Milnes had his copy of Middlemarch specially bound with his armorial stamp.

A recent BBC international survey asked respondents to select the greatest novel in all of English literature. The winner: George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

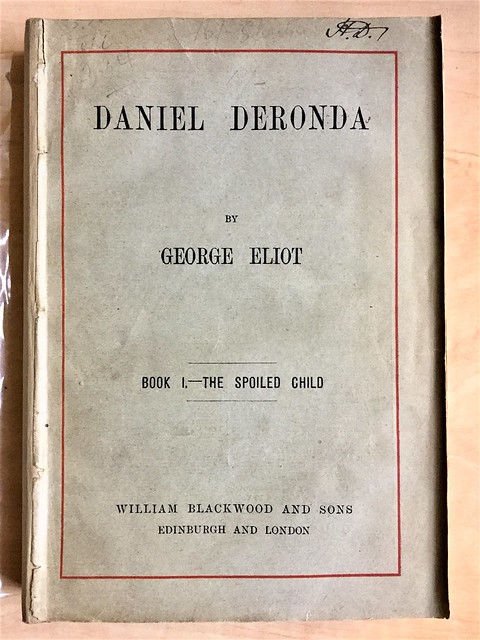

George Eliot’s last published novel was Daniel Deronda. The subject matter of Daniel Deronda is unusual for a Victorian novel: the title character learns that he is Jewish and embraces his heritage, eventually emigrating to Palestine as part of an early Zionist movement.

Like many of her previous works, it was first issued “in parts,” a common practice in the mid-19th century. The novel was published in two-chapter installments, bound in printed paper and released fortnightly.

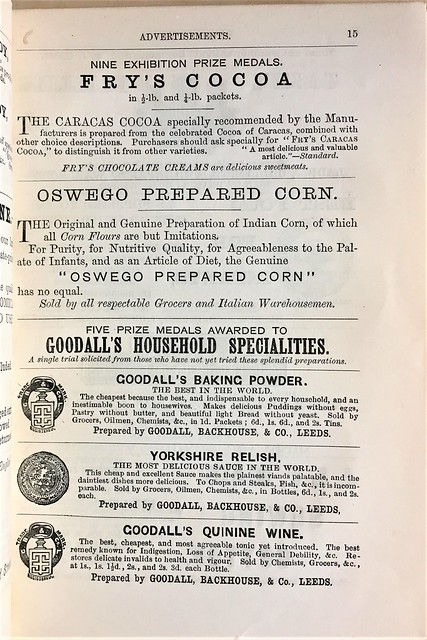

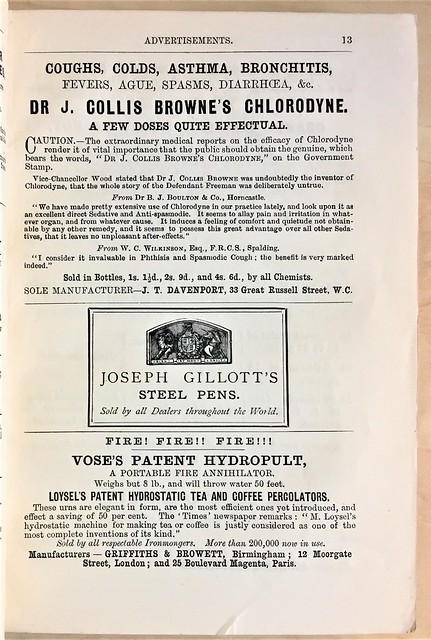

After all of the parts had been issued, a publisher would usually offer a bound monograph of the complete work. One advantage to publishing a popular author’s works in parts was that the publisher could include paid advertisements inside the paper binding. As we can see from the Daniel Deronda parts, these could include ads for just about anything, from cocoa to cough medicine to a “portable fire annihilator.”

George Eliot died in 1880, leaving a literary legacy that shows no sign of abating. ZSR Special Collections’ newly acquired titles join our existing George Eliot holdings to form a robust collection that is already being used by Wake Forest students and faculty. We are grateful to the Newsomes for helping us play a small part in helping future generations of readers appreciate George Eliot and her writings.

4 Comments on ‘George Eliot at 200’

Congratulations for the excellent presentation on November 14th and for this additional report on George Eliot’s writings. I am grateful for the contributions by Dr. Newsome and Jerome Newsome.

Thank you Megan for weaving in the the notes on the past with the current day acquisitions and utilization!

I love the clues left in the books that hint at their history. Fascinating!

Wonderful that you and professors were able to begin using these fantastic volumes right away!