This article is more than 5 years old.

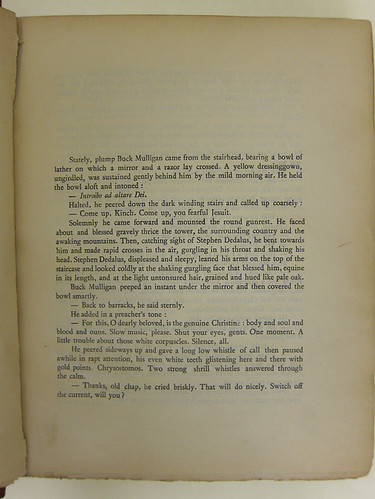

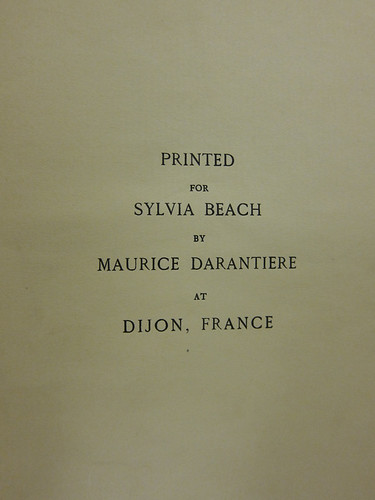

Text page from the first edition of Ulysses

The publishing history of James Joyce’s Ulysses is itself a complicated odyssey.

Joyce began writing Ulysses, a modernist novel detailing one day (16 June 1904) in the life of Dubliner Leopold Bloom, in 1914. By 1918 he was sending typescript chapters to Ezra Pound to be published in installments in the American magazine Little Review. But the publication of the Nausikaa section resulted in an obscenity lawsuit against the the magazine’s publishers, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap.

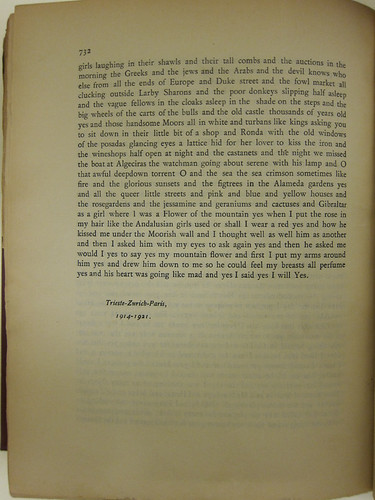

From the Nausikaa section, Shakespeare and Company first edition.

By 1921 the Little Review was bankrupt. Meanwhile Joyce’s friend and benefactor Harriet Weaver approached several English publishers (including Leonard and Virginia Woolf), but none were willing to take on a huge and complex printing project with dubious legal implications.

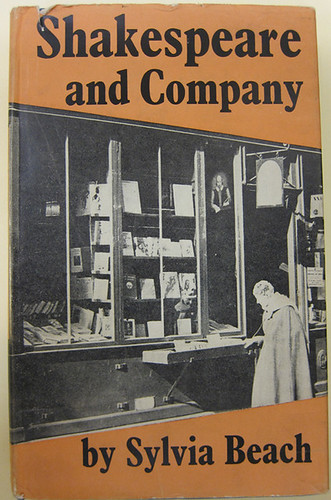

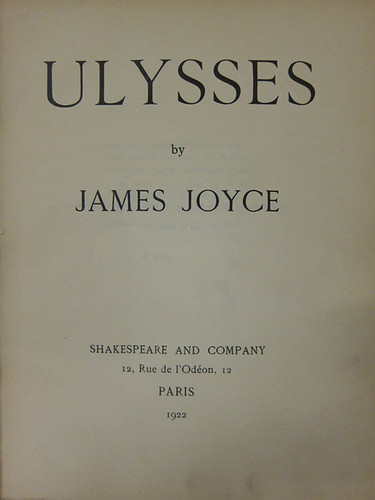

In 1920 Joyce moved to Paris and made the acquaintance of Sylvia Beach, whose bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, was a social center for the American and British expatriate author community. Despite her lack of experience as a publisher, Beach decided to take on Ulysses as a project.

In her 1959 memoir Shakespeare and Company Beach described Joyce’s “complete discouragement” after the Little Review ceased publication:

All hope of publication in the English-speaking countries, at least for a long time to come, was gone. And here in my little bookshop sat James Joyce, sighing deeply.

It occurred to me that something might be done, and I asked : “Would you let Shakespeare and Company have the honour of bringing out your Ulysses?”

He accepted my offer immediately and joyfully. I thought it rash of him to entrust his great Ulysses to such a funny little publisher. But he seemed delighted, and so was I. . . . Undeterred by lack of capital, experience, and all the other requisites of a publisher, I went right ahead with Ulysses. [57]

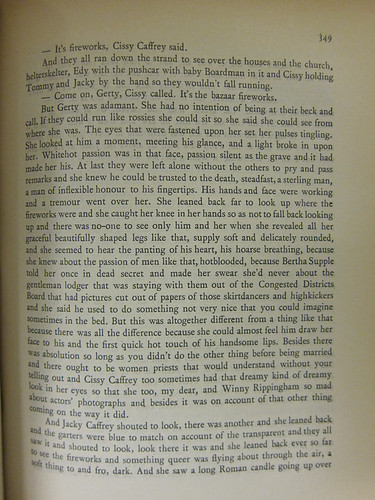

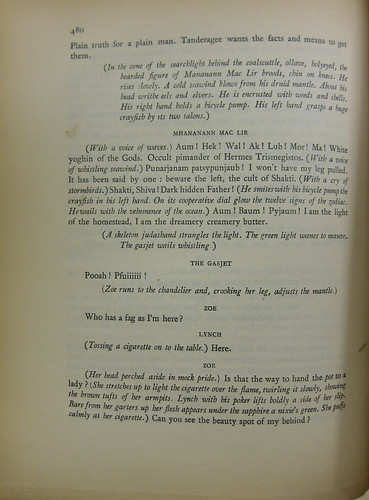

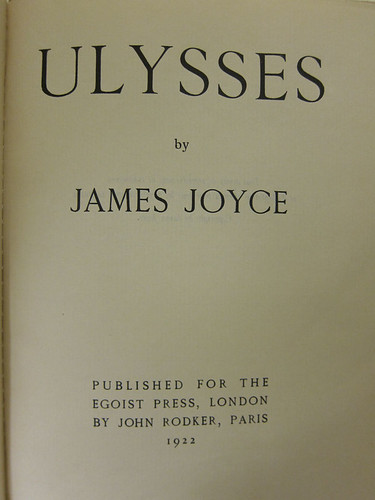

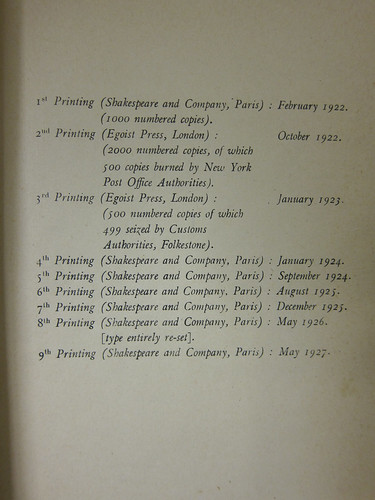

Publisher’s note from the first edition

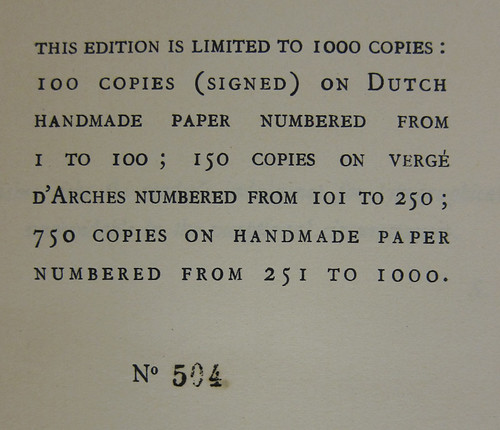

Sylvia Beach found a French printer, Maurice Darantiere, who was willing to print the book essentially on commission. They planned a first edition of 1000 copies (including 100 signed by the author).

Printer’s colophon from the first edition

The process of printing the 700+ page book was complicated for a variety of reasons. Just finding typists who could create useable typescripts from Joyce’s manuscripts was a challenge. Joyce’s writing process involved so many revisions, insertions, and emendations that transcribing them was sometimes nearly impossible. And his nonstandard language and potentially offensive content provided another layer of difficulty. Sylvia Beach recounts how the printing was at one point held up because no typist could be found to complete the Circe section of the manuscript.

Joyce had been trying in vain for some time to get this episode typed. Nine typists had failed in the attempt. The eighth, Joyce told me, threatened in her despair to throw herself out of the window. As for the ninth, she rang the bell at his door and, when it was opened, threw the pages she had done on the floor, then rushed away down the street and disappeared forever. “If she had given me her name and address, at least I could have paid her for her work,” Joyce said. [Beach, 73]

From the Circe section, first edition.

Beach pressed various of her friends and family into service to try to complete the Circe typescript. When one friend’s husband happened to read the manuscript pages she was typing, he was so disgusted that he threw the manuscript into the fire. Photographic copies of the missing pages had to be retrieved, with great difficulty, from the uncooperative American collector to whom Joyce had sold carbon copies of his manuscripts.

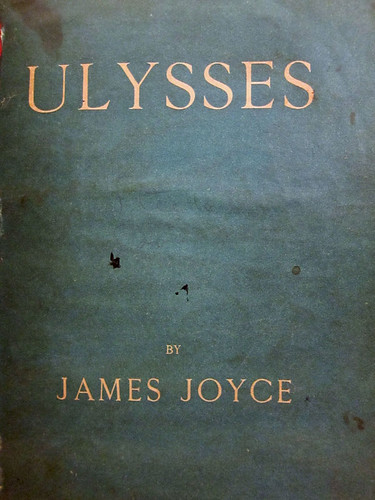

There was even difficulty with finding the right paper for the book’s cover. Joyce wanted the cover to be the blue and white of the Greek flag, but Beach and Darantiere could not find paper in a shade of blue that met with his approval. Finally the resourceful printer found the right blue in Germany and had it lithographed onto white cardboard for the bindings.

Beach had advertised a publication date of autumn 1921 for the first edition of Ulysses, but the many complications in the printing process delayed the project for more than a year. The first copies finally appeared on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s fortieth birthday.

Copies of the book sold briskly at the Shakespeare and Company shop in Paris. Getting books into the hands of the many British and American subscribers proved to be more of a challenge, since the book was banned from distribution through the mail in both countries. But the always resourceful Sylvia Beach found ways to get around the official censorship. At one point she enlisted the help of Ernest Hemingway, who recruited a friend from Toronto (the book was not banned in Canada). A shipment of books for American subscribers was sent to Hemingway’s friend, who then boarded the ferry from Toronto every day with “a copy of Ulysses stuffed down inside his pants” [Beach, 96].

“If Joyce had foreseen all these difficulties,” Beach observed, “maybe he would have written a smaller book.”

Harriet Weaver arranged for an English edition in the same year. Published by John Rodker, the edition was also printed by Darantiere using the same printing plates as Beach’s Paris edition.

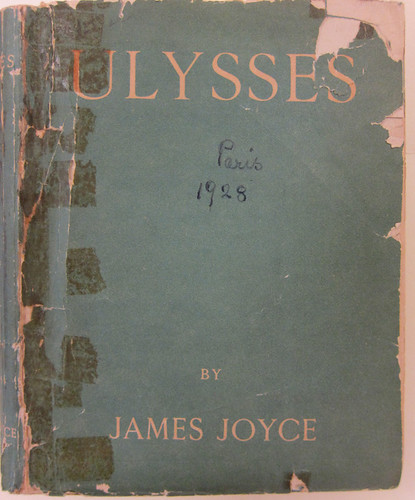

The English edition encountered censorship problems almost immediately, and most copies intended for the British market were confiscated by the authorities. Copies headed for the U.S. met a similar fate, although some were supposedly smuggled into the country disguised as volumes of Shakespeare. Of course, the censorship mostly served to pique interest in Joyce’s novel. A copy of Ulysses was a popular souvenir for American and English visitors to Paris in the 1920s.

A well-worn copy of the Shakespeare and Company second edition, inscribed by its American owner B.W. Walton

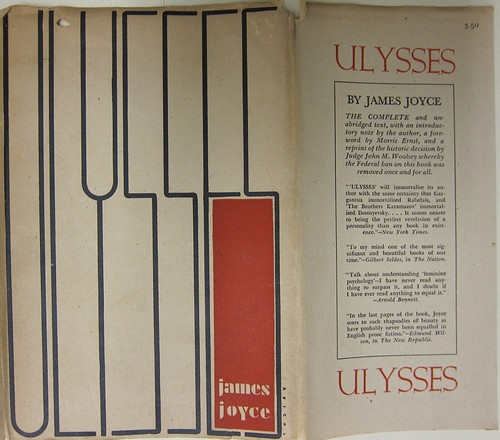

Ulysses was finally cleared of obscenity charges in the U.S. in 1934.

Dust jacket from the first U.S. edition, Random House, 1934

The later publication history of Ulysses was no less complicated. Sylvia Beach published several printings of the first edition and in 1926 brought out a “corrected” second edition.

Edition statement from the Shakespeare and Company second edition, second printing.

Many more editions of Ulysses were published throughout the 20th century, and literary scholars still argue over what constitutes the definitive text of Joyce’s novel.

Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s copy of the first edition of Ulysses was purchased by the library in 1967. The Egoist Press edition was purchased in 1981. Both are part of Special Collections’ extensive Joyce collection.