This article is more than 5 years old.

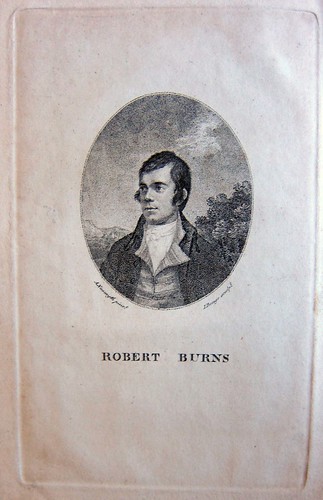

In December of 1786 a young country poet from the west of Scotland traveled to Edinburgh. Robert Burns hoped to drum up support for a second edition of the collection of poems that he had recently published by subscription in Kilmarnock. On 6 December Burns wrote to a friend

I have now been a week in Edin[burgh] and have been introduced to a great many of the Noblesse.—I have met very warm friends in the Literati… [Letters of Robert Burns, 2nd edition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985) 61A]

Shortly thereafter he joked to another friend that

I am in a fair way of becoming as eminent as Thomas a Kempis or John Bunyan; and you may expect henceforth to see my birthday inserted among the wonderful events, in the Poor Robin’s and Aberdeen Almanacks… [Letters 62]

Burns could hardly have imagined that his birthday—January 25—would indeed be celebrated far beyond Aberdeen. Robert Burns Night is commemorated all over the world with food, speeches, and song in honor of the man now widely known as the national poet of Scotland.

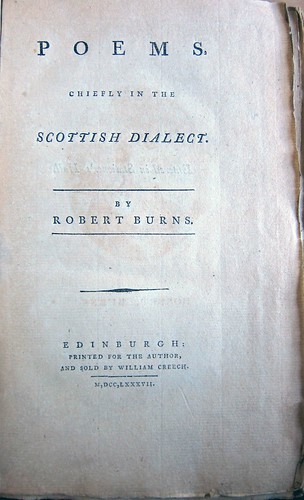

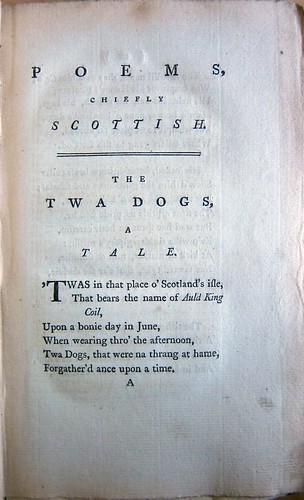

In 1786, however, young Robert Burns was an obscure country poet. The son of a tenant farmer from the southwest of Scotland, Burns always had a talent for poetry and song. He also had a fondness for women, which may have led indirectly to the first publication of his poems. A few months before his trip to Edinburgh, Burns was making plans to emigrate to the West Indies, in part to escape the demands the family of a woman who had recently borne his out-of-wedlock twins. Before quitting Scotland Burns decided to publish a collection of poems based on the traditional dialect and songs of his native land. The very modest volume, titled Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, was printed by John Wilson in Kilmarnock in July 1786, its production paid for by Burns’s friends and supporters.

In October 1786 Burns approached Wilson about the possibility of a second edition, which would include some new poems. But, as Burns recounted in another letter, the printer insisted on an advance of £27 for the paper

[B]ut this, you know, is out of my power; so farewell hopes for a second edition ‘till I grow richer! An epocha, which, I think, will arrive at the payment of the British national debt. [Letters, 53]

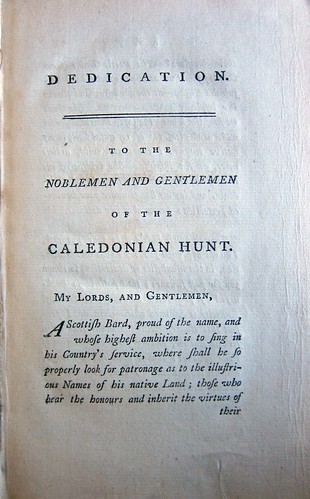

Before leaving the country, Burns decided to make an attempt at finding patronage in the much larger city of Edinburgh, where, he had heard, copies of the Kilmarnock edition had been well received. He was indeed eagerly received by the Edinburgh aristocracy, and he quickly secured the patronage of the Caledonian Hunt –an exclusive social club for Scotland’s wealthiest men—for the second edition of his Poems.

Much of Burns’s stay in Edinburgh was taken up with preparations for this second edition, which included some new poems not found in the Kilmarnock edition. Writing to one of his partrons in March 1787, Burns records that

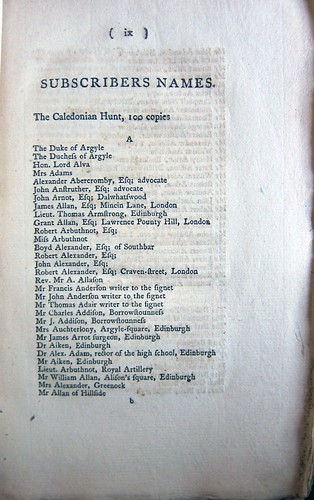

I have today corrected the last proof sheet of my poems and have now only the Glossary and subscribers names to print. . . . Printing this last is much against my will, but some of my friends whom I do not chuse to thwart will have it so. – I have both a second and a third Edition going on as the second was begun with too small a number of copies.—The whole I have printed is three thousand. [Letters, 90]

The average edition size at the time for a work of poetry was under 1000 copies, so an edition of 3000 copies was clear evidence of Burns’s ascendant fame. And the 46-page list, printed at the beginning of the volume, of names and tiles of subscribers provided incontrovertible evidence that the literary elite of Scotland had given their approval.

Robert Burns was a gifted poet, but he also had the advantage of appearing at the right time. The antiquarian movement of the 18th century had brought about great interest in the literature and material culture of the distant past. And in Scotland, antiquarianism had a decidedly nationalistic bent. English language and culture had been encroaching in Scotland since the union of the two kingdoms in 1603, and Burns’s poetry provided a direct link to traditional Scottish folkways and dialects. Burns himself embraced his identity as a national poet, writing in 1787:

The appellation of, a Scotch Bard, is by far my highest pride; to continue to deserve it is my most exalted ambition.—Scottish scenes, and Scottish story are the themes I could wish to sing… [Letters, 90]

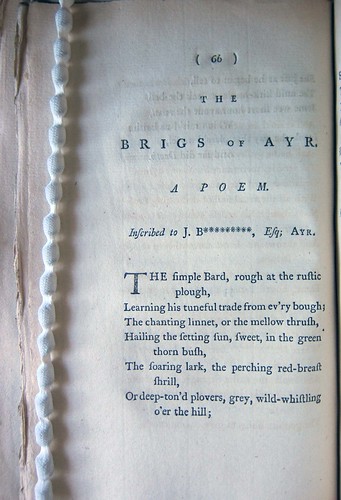

Among the new poems included Edinburgh edition was “The Brigs of Ayr”—a dialogue between old and new bridges over the river Ayr– dedicated to his friend and longtime patron John Ballantine. The desire to see this poem in print was a motivating factor in Burns’s publishing a second edition. In 1786, despairing of being able to raise money for a second Kilmarnock edition, Burns wrote

There is scarcely any thing hurts me so much in being disappointed of my second edition, as not having it in my power to shew my gratitude to Mr. Ballantine, by publishing my poem of The Brigs of Ayr . [Letters, 53]

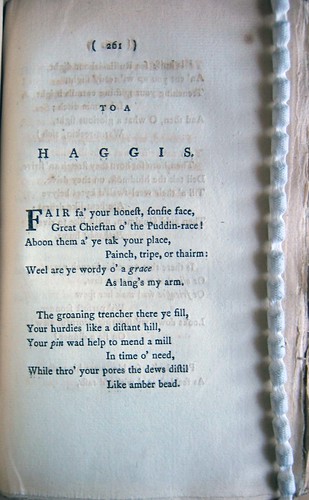

Burns’s ode to haggis was likely responsible for this rather off-putting concoction (offal, onions, and oatmeal boiled in a sheep’s stomach) being enshrined as the national dish of Scotland.

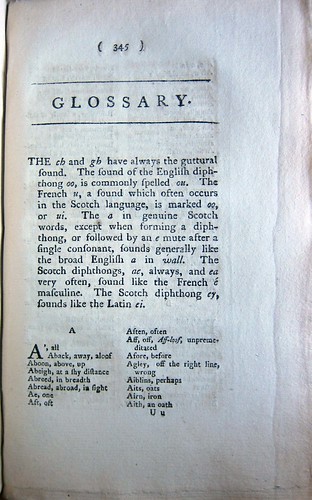

The glossary included in the Edinburgh edition of Burns’s Poems preserves distinctively Scottish words and pronunciations. But the fact that even his fellow Scots needed a guide to the language attests that the dialect was rapidly disappearing from everyday use.

The Edinburgh edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect made Burns’s reputation. It also gave him financial security, at least temporarily. On the eve of its publication Burns wrote that

I guess I shall clear between two and three hundred pounds by my Authorship; with that sum I intend, so far as I may be said to have any intention, to return to my old acquaintance, the plough, and, if I can meet with a lease by which I can live, to commence Farmer. [Letters, 90]

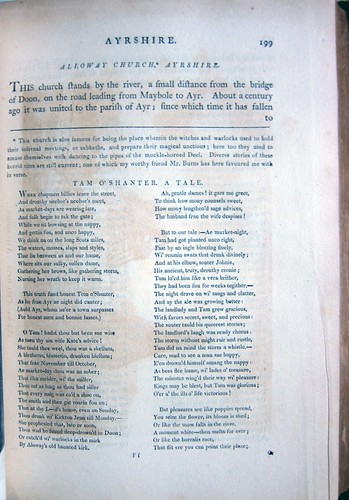

Burns did indeed go back to farming, at least for a while. He married the mother of his twin children and fathered several more children. Eventually he took on a job as an excise officer in Dumfries. But he continued to write poetry and continued to take an active interest in the study and preservation of Scottish culture. One of his best known poems, “Tam o’Shanter,” was published in a volume dedicated to the preservation of Scottish buildings and monuments.

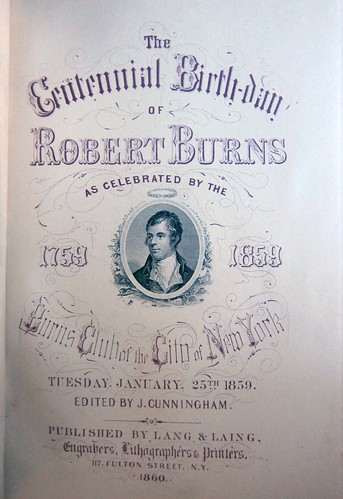

Burns died suddenly in 1796 at the age of only 37. But enthusiasm for his poetry never flagged. Memoirs, tributes, and collections of his works were published, and the 1859 centennial of his birth was the occasion for many celebrations.

Since then the tradition of commemorating Burns Night on January 25 has spread throughout the world. Robert Burns would no doubt be delighted that his writings have brought the songs and poetry of his beloved Scotland to a global audience.

ZSR’s copy of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect is from the Charles Babcock collection. It is particularly interesting as an artifact because it has never been altered or rebound. With its original printer’s cardboard binding and untrimmed pages, the book is exactly what an 18th century reader would have purchased from an Edinburgh bookseller.

4 Comments on ‘Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, by Robert Burns (1787)’

Megan, I always enjoy learning about items in Special Collections, and today I did so with my Saturday morning coffee! I especially liked the detail regarding the £27 for the paper. Nothing is free, even back then!

I am sending this to Ryan Shirey, our Scottish literature scholar!

This is wonderful, Megan. How exciting to learn that we have such a great copy at Wake! I’m a little embarrassed that I didn’t know this! Thanks so much for sharing.

When I was a child my parent celebrated Robert Burns’ birthday by having haggis for supper. I enjoyed it and I enjoyed reading this post. Thank you, Megan!